William H. Gass at 100: Looking backward, Looking forward

This paper was presented at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture, held Feb. 22-24, 2024, at the University of Louisville. Another paper in the “Novel Focus” panel were “Emma Donoghue’s Hunger Aesthetic” by Carey Mickalites (University of Memphis). The panel was chaired by Marie Pruitt (University of Louisville).

• • •

Where to begin?

I suppose with this quote: “William H. Gass is not an easy man to grasp; and, like the man, his work is beautiful, formidable, and troubling all at once,” wrote Theodore G. Ammon in the introduction to Conversations with William H. Gass (2003). There is no shortage of opinions of and therefore quotes pertaining to him and his work, which, thankfully, is copious: fiction ranging from brief sketches to the epic novel The Tunnel; nonfiction in the form of essays, criticism, lectures, and reviews, much of which collected in ten volumes over more than forty years; plus translations, interviews, and the thousands of pages of letters, early drafts, publication proofs, teaching notes, and even his doctoral dissertation (archived at Washington University in St. Louis, where he spent the last 32 years of his professional life).

I like this quote from Ammon, though, to begin this paper because it’s in conjunction with the William H. Gass centenary. Born in Fargo, North Dakota, in 1924, Gass was a prolific author (despite the difficulty he always claimed to have in composing, and the slow pace by which much of his work—especially his fiction—emerged), toiling away with words almost until his death in 2017 at the age of 93. It seems to me that one of the goals of this year, 2024, and perhaps its chief goal, is to try to capture and honor the essence of Gass’s contributions to not just American literature but also to literature beyond the borders of the United States (Gass dedicated the last decade of his time at Washington University to founding and directing the International Writers Center). I’ll ape Ammon’s quote by saying that this Gass-focused goal is not an easy one to achieve.

I mean the title of this paper to be quite literal. I will devote a good deal of it to looking backward by outlining (if only superficially) Gass’s many interests and accomplishments over the decades; and I will end by looking forward, both in the short term (what else is happening this year as part of the Gass centenary) and the long term (where might scholarly energies be devoted over time). I apologize to anyone who is already quite familiar with Gass: the first part of this presentation may seem basic and unnecessary. However, I’m always a little ashamed to acknowledge that I was in my mid-forties when I first read Gass’s work, and I was not alone in my ignorance. For the past fifteen years I’ve devoted myself to what one of my students dubbed “preaching the Gass-pel,” and I have encountered many well-read scholars and devoted readers who have never heard of Gass, or who only have a passing familiarity with him and his work.

Looking backward.

Gass was always doing everything all at once. That is to say, he didn’t devote himself to a kind of writing for a certain period of his life; then to another kind for a time; then another and so on. Like so many of the writers that Gass admired—Henry James, Virginia Woolf, Samuel Beckett, Jorge Luis Borges—his interests were wide-ranging, and he was forever juggling multiple projects. For convenience, I’ll give an overview organized by kind of writing. His varying interests are illustrated by the journal that was the first to publish his fiction. Accent: A Quarterly of New Literature (published by University of Illinois, Urbana), included the short story “Mrs. Mean” and the opening section of what would become his debut novel, “The Triumph of Israbestis Tott.” In the same issue, Accent also brought out “The High Brutality of Good Intentions,” an essay on Henry James.

“Mrs. Mean” (Accent, winter 1958, later collected in In the Heart of the Heart of the Country) was reprinted in Best American Short Stories (1959), which may have begun the process of having Gass’s fiction read by a broader national audience. The 1961 edition of Best American Short Stories included Gass’s “The Love and Death of Henry Pimber” (Accent, spring 1960); and the 1962 edition included “The Pedersen Kid” (MSS [Mt. Shasta Selections], no. 1, 1961). Throughout this period, Gass was regularly publishing short fiction, scholarly essays, and book reviews in academic journals. However, it was the publication of his debut novel, Omensetter’s Luck, in 1966 (New American Library) that really put his name on the national literary map. The novel won high praise from a host of reviewers. The fact that it was published by New American Library was significant because it brought Gass to the attention of Theodore Solotaroff, editor of New American Review literary journal, which was published by New American Library and was launched in 1967. Gass’s “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” was in the inaugural issue—the first of four appearances in the journal.

As you may know, New American Review was published as a mass market paperback, and distributed nationally via bookstores and newsstands, but also drug stores, supermarkets, and other places where literary journals were not commonly available. In the beginning (when Gass’s work was included), 100,000 copies of each issue were printed, and there were three issues annually. Gass’s work, both fiction and nonfiction, was appearing alongside writers and poets like Grace Paley, Philip Roth, Anne Sexton, Russell Banks, Jorge Luis Borges, Marvin Bell and Louise Gluck.

Other important book publications were soon to follow: in 1968, both the wildly experimental novella Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife (originally TriQuarterly in a limited edition, then reprinted by Knopf, 1971), and In the Heart of the Heart of the Country and Other Stories (Harper & Row). Gass’s first collection of nonfiction was released in 1970 by Knopf, Fiction and the Figures of Life.

It was also during the late 1960s that Gass began writing The Tunnel. In fact, it first began to appear in print in New American Review, with “We Have Not Lived the Right Life” (no. 6, 1969). The novel would not be published until 1995, and over the more than quarter century that Gass worked on it, excerpts would appear in a host of noteworthy journals and magazines, including The Paris Review, Kenyon Review, Salmagundi, and Esquire. Meanwhile, the excerpts were reprinted numerous times as part of “best of” anthologies and as Pushcart and Best American Short Stories prizewinners. Nevertheless, Gass said in 1971, half jokingly and half seriously, that he hoped The Tunnel “will be such a good book no one will want to publish it” (McCauley 12); and his wish nearly came true. The book had been under contract to Boston-based Ticknor and Fields, but once the manuscript was finally complete in 1992, they withdrew the contract. Dalkey Archive Press entertained the idea of publishing what Steven Moore described as a “huge manuscript, along with a lengthy set of design and typesetting instructions.” Ultimately Knopf brought out the first edition in 1995, only to let it go out of print shortly thereafter. Dalkey stepped in to publish a paperback edition in 1999.

The Tunnel won the American Book Award in 1996, and it had its fervent admirers, but it also generated many reviews that ranged from tepid to hostile. The Tunnel turned 25 in 2020, during the pandemic, so I initiated an online symposium, available at thetunnelat25.com. I encourage you to check out all of the site’s contributions, but since I’m focused at the moment on the novel’s publishing history I’ll highlight two pieces in particular: “The Tunnel: A Survey of Published Excerpts” by Joel Minor; and my own “The Tunnel: A Chronology & Bibliography.” The two papers have similar aims, yet contain different information. Joel’s important contribution focuses in great detail on the publishing history of the various excerpts, and cross-references them with material that is available at Washington University in the William H. Gass papers (of which Joel is the curator). My paper, on the other hand, is more interested in Gass’s writing process, and tracks the composition of the novel alongside Gass’s biography. For example, I’ve integrated some of Gass’s comments about the novel year by year, drawing from the many interviews he granted.

While Gass was writing The Tunnel, he was also working on a series of novellas that was ultimately published as Cartesian Sonata and Other Novellas (Knopf, 1998), but the title novella began to appear in 1964, as “The Clairvoyant” in Location, volume 1, number 2. During the same period that parts of The Tunnel were appearing in journals, being reprinted and winning prizes, bits and pieces of Cartesian Sonata were taking similar paths, coming out in places like Art and Literature, The Partisan Review, and the Iowa Review, being anthologized here and there, and winning a Pushcart Prize in 1976. As a side note, I feel like the Cartesian Sonata collection is Gass’s most masterful masterpiece (even though The Tunnel tends to overshadow the rest of Gass’s fiction in terms of scholars’ attention and cultural memory), and I’ll make my case when I deliver a paper at the American Literature Association Conference in May.

In the interest of time, I’ll summarize the remainder of Gass’s output of fiction: the novel Middle C (Knopf, 2013) and Eyes, a collection of novellas and stories (Knopf, 2015). Much of these final two works appeared in Conjunctions, which became an important outlet for Gass’s writing, both fiction and nonfiction, starting in the early 1980s and lasting until his death in 2017. He eventually became a contributing editor of the journal and was a central figure in several Conjunctions projects.

Fiction, of course, is only part of Gass’s legacy. For the remainder of my time I’ll discuss the “looking forward” aspect of my title—and in so doing also provide a sense of other facets of William Gass’s voluminous output and his far-reaching influence on the literary community, including the global literary community.

While Gass was writing stories, novellas and novels, he was also prolifically producing nonfiction in the form of essays, reviews, book introductions, and lectures. He published seven works of fiction, and he published ten works of nonfiction (if one counts the collection of interviews edited by Theodore Ammon in 2003). Moreover, he served as co-editor of three collections of nonfiction, including The Writer and Politics (1996) and The Writer and Religion (2000). Broadly speaking, Gass’s nonfiction has not received nearly as much critical attention as his fiction, even though his work was highly influential, including among his peers. We know, for instance, that Fiction and the Figures of Life—which includes several “craft” essays—was acquired by Cormac McCarthy while he was at work on Child of God, published in 1973, three years after the release of Gass’s essay collection (King 31).

In addition to the eight collections of nonfiction (here not counting the book-length essay On Being Blue), Gass’s vita lists about 100 uncollected essays, reviews, introductions, and lectures. Fortunately, Washington University in St. Louis started archiving Gass’s work even before he began teaching there in 1969. It’s difficult to say, but the Gass collection, begun in the mid-60s but reaching back as far as 1948, consists of thousands of items, and it keeps expanding as Gass’s widow, Mary Henderson Gass, continues the work of sorting and cataloging her late husband’s papers and contributing them to the archive in batches.

Besides the possibility of posthumous publications, there is limitless potential here for scholarly research and writing. William Gass has been the main focus of my scholarship for the past 15 years, and I’ve visited the Gass archive several times, which has proven to be the epitome of scratching the surface.

In addition to Gass’s fiction and nonfiction, other rich veins of scholarship could include the following abbreviated list:

Gass’s support and promotion of other writers, including and perhaps especially writers outside the U.S. For the final decade of his professional career, Gass directed the International Writers Center at Washington University, a Center that he founded in 1990. Its mission was to “build on the strengths of its resident and visiting faculty writers; to serve as a focal point for writing excellence in all disciplines and in all cultures; to be a directory for writers and writing programs at Washington University, in St. Louis, in the United States, and around the world; and to present the writer to the reader” (“William H. Gass”).

Gass’s frequent writing of book reviews. He penned both reviews of scholarly books (especially early in his career) as well as more mainstream books. He was a regular contributor to The New York Times Book Review, but also The Times Literary Supplement and other venues. Furthermore, Gass established a reputation as a writer of introductions for others’ books—perhaps most famously his introduction to William Gaddis’s The Recognitions (Penguin Classics edition). Michael Millman, senior editor at Viking Penguin, wrote to Gass on January 21, 1993: “I can’t remember another time when we had an essay of this caliber as an introduction to one of our volumes. . . .” But the list is long and includes introductions to books by or about Gertrude Stein, John Hawkes, Robert Coover, Stanley Elkin, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Gass as educator. Gass’s primary teaching posts were at Purdue University and Washington University, and he proved to be an award-winning educator at both institutions. Beyond that direct influence on countless students, Gass’s writings serve as teaching material for an untold number of educators. His fiction and essays have been widely anthologized (I first encountered Gass in an anthology), thus serving as models. Moreover, his essays—particularly his craft-focused essays—are the bases for others’ lectures and teaching notes. Plus Gass was a generous granter of interviews, nearly all of which contain discussion of tecnique that ranges from the practical to the theoretical. Fourteen interviews are collected in Conversations with William H. Gass, but this book represents the proverbial tip of the iceberg. There are many interviews online, as text, video and audio, in addition to copious uncollected interviews in print. All of these interviews are rich sources of material for teachers and students of writing.

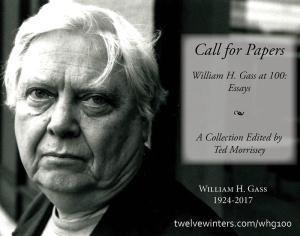

I’ll end by mentioning that in this, Gass’s centenary year, I’ll be editing and publishing a collection of essays—and there is ample time to contribute to that project. See the CFP here. Also, this fall there will be a conference at Washington University in St. Louis. The specifics are still being worked out, but it will likely focus on Gass’s On Being Blue, which was re-released by New York Review Books in 2014. And as a footnote, another resource for Gass studies is this blog, where all of my Gass conference papers are archived. One can get hold of a significant chunk of Gass’s writing in The William H. Gass Reader (Knopf, 2018), writing that was handpicked and annotated by Gass before his death. For a detailed overview, see my rather lengthy review of the Reader at the North American Review website.

Works Cited

Ammon, Theodore G., editor. Conversations with William H. Gass. UP of Mississippi, 2003.

King, Daniel Robert. Cormac McCarthy’s Literary Evolution: Editors, Agents, and the Crafting of a Prolific American Author, The U of Tennessee P, 2016.

McCauley, Carole Spearin. “William H. Gass.” Ammon, pp. 3-12.

Moore, Steven. Dalkey Days: A Memoir. Zerogram Press, 2023.

“William H. Gass.” University Libraries, Washington University in St. Louis, 16 Feb. 2024, https://library.wustl.edu/spec/william-h-gass/.

leave a comment