William H. Gass at 100: Looking backward, Looking forward

This paper was presented at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture, held Feb. 22-24, 2024, at the University of Louisville. Another paper in the “Novel Focus” panel were “Emma Donoghue’s Hunger Aesthetic” by Carey Mickalites (University of Memphis). The panel was chaired by Marie Pruitt (University of Louisville).

• • •

Where to begin?

I suppose with this quote: “William H. Gass is not an easy man to grasp; and, like the man, his work is beautiful, formidable, and troubling all at once,” wrote Theodore G. Ammon in the introduction to Conversations with William H. Gass (2003). There is no shortage of opinions of and therefore quotes pertaining to him and his work, which, thankfully, is copious: fiction ranging from brief sketches to the epic novel The Tunnel; nonfiction in the form of essays, criticism, lectures, and reviews, much of which collected in ten volumes over more than forty years; plus translations, interviews, and the thousands of pages of letters, early drafts, publication proofs, teaching notes, and even his doctoral dissertation (archived at Washington University in St. Louis, where he spent the last 32 years of his professional life).

I like this quote from Ammon, though, to begin this paper because it’s in conjunction with the William H. Gass centenary. Born in Fargo, North Dakota, in 1924, Gass was a prolific author (despite the difficulty he always claimed to have in composing, and the slow pace by which much of his work—especially his fiction—emerged), toiling away with words almost until his death in 2017 at the age of 93. It seems to me that one of the goals of this year, 2024, and perhaps its chief goal, is to try to capture and honor the essence of Gass’s contributions to not just American literature but also to literature beyond the borders of the United States (Gass dedicated the last decade of his time at Washington University to founding and directing the International Writers Center). I’ll ape Ammon’s quote by saying that this Gass-focused goal is not an easy one to achieve.

I mean the title of this paper to be quite literal. I will devote a good deal of it to looking backward by outlining (if only superficially) Gass’s many interests and accomplishments over the decades; and I will end by looking forward, both in the short term (what else is happening this year as part of the Gass centenary) and the long term (where might scholarly energies be devoted over time). I apologize to anyone who is already quite familiar with Gass: the first part of this presentation may seem basic and unnecessary. However, I’m always a little ashamed to acknowledge that I was in my mid-forties when I first read Gass’s work, and I was not alone in my ignorance. For the past fifteen years I’ve devoted myself to what one of my students dubbed “preaching the Gass-pel,” and I have encountered many well-read scholars and devoted readers who have never heard of Gass, or who only have a passing familiarity with him and his work.

Looking backward.

Gass was always doing everything all at once. That is to say, he didn’t devote himself to a kind of writing for a certain period of his life; then to another kind for a time; then another and so on. Like so many of the writers that Gass admired—Henry James, Virginia Woolf, Samuel Beckett, Jorge Luis Borges—his interests were wide-ranging, and he was forever juggling multiple projects. For convenience, I’ll give an overview organized by kind of writing. His varying interests are illustrated by the journal that was the first to publish his fiction. Accent: A Quarterly of New Literature (published by University of Illinois, Urbana), included the short story “Mrs. Mean” and the opening section of what would become his debut novel, “The Triumph of Israbestis Tott.” In the same issue, Accent also brought out “The High Brutality of Good Intentions,” an essay on Henry James.

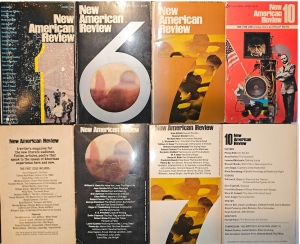

“Mrs. Mean” (Accent, winter 1958, later collected in In the Heart of the Heart of the Country) was reprinted in Best American Short Stories (1959), which may have begun the process of having Gass’s fiction read by a broader national audience. The 1961 edition of Best American Short Stories included Gass’s “The Love and Death of Henry Pimber” (Accent, spring 1960); and the 1962 edition included “The Pedersen Kid” (MSS [Mt. Shasta Selections], no. 1, 1961). Throughout this period, Gass was regularly publishing short fiction, scholarly essays, and book reviews in academic journals. However, it was the publication of his debut novel, Omensetter’s Luck, in 1966 (New American Library) that really put his name on the national literary map. The novel won high praise from a host of reviewers. The fact that it was published by New American Library was significant because it brought Gass to the attention of Theodore Solotaroff, editor of New American Review literary journal, which was published by New American Library and was launched in 1967. Gass’s “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” was in the inaugural issue—the first of four appearances in the journal.

As you may know, New American Review was published as a mass market paperback, and distributed nationally via bookstores and newsstands, but also drug stores, supermarkets, and other places where literary journals were not commonly available. In the beginning (when Gass’s work was included), 100,000 copies of each issue were printed, and there were three issues annually. Gass’s work, both fiction and nonfiction, was appearing alongside writers and poets like Grace Paley, Philip Roth, Anne Sexton, Russell Banks, Jorge Luis Borges, Marvin Bell and Louise Gluck.

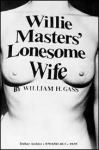

Other important book publications were soon to follow: in 1968, both the wildly experimental novella Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife (originally TriQuarterly in a limited edition, then reprinted by Knopf, 1971), and In the Heart of the Heart of the Country and Other Stories (Harper & Row). Gass’s first collection of nonfiction was released in 1970 by Knopf, Fiction and the Figures of Life.

It was also during the late 1960s that Gass began writing The Tunnel. In fact, it first began to appear in print in New American Review, with “We Have Not Lived the Right Life” (no. 6, 1969). The novel would not be published until 1995, and over the more than quarter century that Gass worked on it, excerpts would appear in a host of noteworthy journals and magazines, including The Paris Review, Kenyon Review, Salmagundi, and Esquire. Meanwhile, the excerpts were reprinted numerous times as part of “best of” anthologies and as Pushcart and Best American Short Stories prizewinners. Nevertheless, Gass said in 1971, half jokingly and half seriously, that he hoped The Tunnel “will be such a good book no one will want to publish it” (McCauley 12); and his wish nearly came true. The book had been under contract to Boston-based Ticknor and Fields, but once the manuscript was finally complete in 1992, they withdrew the contract. Dalkey Archive Press entertained the idea of publishing what Steven Moore described as a “huge manuscript, along with a lengthy set of design and typesetting instructions.” Ultimately Knopf brought out the first edition in 1995, only to let it go out of print shortly thereafter. Dalkey stepped in to publish a paperback edition in 1999.

The Tunnel won the American Book Award in 1996, and it had its fervent admirers, but it also generated many reviews that ranged from tepid to hostile. The Tunnel turned 25 in 2020, during the pandemic, so I initiated an online symposium, available at thetunnelat25.com. I encourage you to check out all of the site’s contributions, but since I’m focused at the moment on the novel’s publishing history I’ll highlight two pieces in particular: “The Tunnel: A Survey of Published Excerpts” by Joel Minor; and my own “The Tunnel: A Chronology & Bibliography.” The two papers have similar aims, yet contain different information. Joel’s important contribution focuses in great detail on the publishing history of the various excerpts, and cross-references them with material that is available at Washington University in the William H. Gass papers (of which Joel is the curator). My paper, on the other hand, is more interested in Gass’s writing process, and tracks the composition of the novel alongside Gass’s biography. For example, I’ve integrated some of Gass’s comments about the novel year by year, drawing from the many interviews he granted.

While Gass was writing The Tunnel, he was also working on a series of novellas that was ultimately published as Cartesian Sonata and Other Novellas (Knopf, 1998), but the title novella began to appear in 1964, as “The Clairvoyant” in Location, volume 1, number 2. During the same period that parts of The Tunnel were appearing in journals, being reprinted and winning prizes, bits and pieces of Cartesian Sonata were taking similar paths, coming out in places like Art and Literature, The Partisan Review, and the Iowa Review, being anthologized here and there, and winning a Pushcart Prize in 1976. As a side note, I feel like the Cartesian Sonata collection is Gass’s most masterful masterpiece (even though The Tunnel tends to overshadow the rest of Gass’s fiction in terms of scholars’ attention and cultural memory), and I’ll make my case when I deliver a paper at the American Literature Association Conference in May.

In the interest of time, I’ll summarize the remainder of Gass’s output of fiction: the novel Middle C (Knopf, 2013) and Eyes, a collection of novellas and stories (Knopf, 2015). Much of these final two works appeared in Conjunctions, which became an important outlet for Gass’s writing, both fiction and nonfiction, starting in the early 1980s and lasting until his death in 2017. He eventually became a contributing editor of the journal and was a central figure in several Conjunctions projects.

Fiction, of course, is only part of Gass’s legacy. For the remainder of my time I’ll discuss the “looking forward” aspect of my title—and in so doing also provide a sense of other facets of William Gass’s voluminous output and his far-reaching influence on the literary community, including the global literary community.

While Gass was writing stories, novellas and novels, he was also prolifically producing nonfiction in the form of essays, reviews, book introductions, and lectures. He published seven works of fiction, and he published ten works of nonfiction (if one counts the collection of interviews edited by Theodore Ammon in 2003). Moreover, he served as co-editor of three collections of nonfiction, including The Writer and Politics (1996) and The Writer and Religion (2000). Broadly speaking, Gass’s nonfiction has not received nearly as much critical attention as his fiction, even though his work was highly influential, including among his peers. We know, for instance, that Fiction and the Figures of Life—which includes several “craft” essays—was acquired by Cormac McCarthy while he was at work on Child of God, published in 1973, three years after the release of Gass’s essay collection (King 31).

In addition to the eight collections of nonfiction (here not counting the book-length essay On Being Blue), Gass’s vita lists about 100 uncollected essays, reviews, introductions, and lectures. Fortunately, Washington University in St. Louis started archiving Gass’s work even before he began teaching there in 1969. It’s difficult to say, but the Gass collection, begun in the mid-60s but reaching back as far as 1948, consists of thousands of items, and it keeps expanding as Gass’s widow, Mary Henderson Gass, continues the work of sorting and cataloging her late husband’s papers and contributing them to the archive in batches.

Besides the possibility of posthumous publications, there is limitless potential here for scholarly research and writing. William Gass has been the main focus of my scholarship for the past 15 years, and I’ve visited the Gass archive several times, which has proven to be the epitome of scratching the surface.

In addition to Gass’s fiction and nonfiction, other rich veins of scholarship could include the following abbreviated list:

Gass’s support and promotion of other writers, including and perhaps especially writers outside the U.S. For the final decade of his professional career, Gass directed the International Writers Center at Washington University, a Center that he founded in 1990. Its mission was to “build on the strengths of its resident and visiting faculty writers; to serve as a focal point for writing excellence in all disciplines and in all cultures; to be a directory for writers and writing programs at Washington University, in St. Louis, in the United States, and around the world; and to present the writer to the reader” (“William H. Gass”).

Gass’s frequent writing of book reviews. He penned both reviews of scholarly books (especially early in his career) as well as more mainstream books. He was a regular contributor to The New York Times Book Review, but also The Times Literary Supplement and other venues. Furthermore, Gass established a reputation as a writer of introductions for others’ books—perhaps most famously his introduction to William Gaddis’s The Recognitions (Penguin Classics edition). Michael Millman, senior editor at Viking Penguin, wrote to Gass on January 21, 1993: “I can’t remember another time when we had an essay of this caliber as an introduction to one of our volumes. . . .” But the list is long and includes introductions to books by or about Gertrude Stein, John Hawkes, Robert Coover, Stanley Elkin, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Gass as educator. Gass’s primary teaching posts were at Purdue University and Washington University, and he proved to be an award-winning educator at both institutions. Beyond that direct influence on countless students, Gass’s writings serve as teaching material for an untold number of educators. His fiction and essays have been widely anthologized (I first encountered Gass in an anthology), thus serving as models. Moreover, his essays—particularly his craft-focused essays—are the bases for others’ lectures and teaching notes. Plus Gass was a generous granter of interviews, nearly all of which contain discussion of tecnique that ranges from the practical to the theoretical. Fourteen interviews are collected in Conversations with William H. Gass, but this book represents the proverbial tip of the iceberg. There are many interviews online, as text, video and audio, in addition to copious uncollected interviews in print. All of these interviews are rich sources of material for teachers and students of writing.

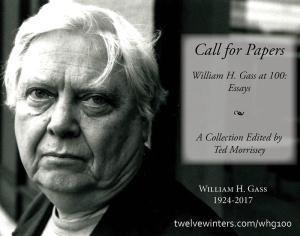

I’ll end by mentioning that in this, Gass’s centenary year, I’ll be editing and publishing a collection of essays—and there is ample time to contribute to that project. See the CFP here. Also, this fall there will be a conference at Washington University in St. Louis. The specifics are still being worked out, but it will likely focus on Gass’s On Being Blue, which was re-released by New York Review Books in 2014. And as a footnote, another resource for Gass studies is this blog, where all of my Gass conference papers are archived. One can get hold of a significant chunk of Gass’s writing in The William H. Gass Reader (Knopf, 2018), writing that was handpicked and annotated by Gass before his death. For a detailed overview, see my rather lengthy review of the Reader at the North American Review website.

Works Cited

Ammon, Theodore G., editor. Conversations with William H. Gass. UP of Mississippi, 2003.

King, Daniel Robert. Cormac McCarthy’s Literary Evolution: Editors, Agents, and the Crafting of a Prolific American Author, The U of Tennessee P, 2016.

McCauley, Carole Spearin. “William H. Gass.” Ammon, pp. 3-12.

Moore, Steven. Dalkey Days: A Memoir. Zerogram Press, 2023.

“William H. Gass.” University Libraries, Washington University in St. Louis, 16 Feb. 2024, https://library.wustl.edu/spec/william-h-gass/.

Preface to ‘First Kings and Other Stories’

I am delighted that Wordrunner eChapbooks has brought out First Kings and Other Stories, which functions on multiple levels. It is, as the title implies, a collection of stand-alone stories. The stories are interconnected, though, and work together as an independent novella. They also represent a work in progress–a novel that takes place over a 24-hour period in 1907 (as I am envisioning it now).

This larger work in progress is a further evolution of a concept I experimented with in my novel Crowsong for the Stricken (2017), in that each piece was designed to work on the microcosmic as well as the macrocosmic level, meaning that each piece could be read as a fully realized short story while also contributing a vital piece to the macrocosm of the novel. Crowsong was mainly set in 1957, in an isolated, unnamed Midwestern village, but the narrative structure is deliberately indeterminate. That is, my hope was that readers would encounter the twelve pieces in an order of their own choosing. The various possible combinations would change the reader’s experience of the novel as a whole. I called it a “prismatic novel” for this reason.

I am trying to take the idea further in this current work in progress. Similar to Crowsong, each piece is intended to function on both the micro- and macrocosmic levels, but the structure is much tighter, both in terms of narrative timing and in the number of interlocking pieces. It is challenging. Not infrequently, when writing, I think of a plot advancement or some other detail that would work quite nicely in the limited world of the short story, but it would throw off, or even contradict, something in the more expansive world of the novel of which it is also part. At the same time, the connective tissue I’m building within each piece so that it harmonizes with the whole must fit seamlessly in the short story, too.

So far it seems to be working. The title story, “First Kings,” appeared originally in North American Review and was reprinted in Sequestrum. The second piece, “Hosea,” was published by Belle Ombre. Quite honestly, it was the third story, “The Widow’s Son,” that prompted me to send the entire manuscript (as it stood at the time) to Wordrunner when they put out a call for novella-length submissions. “The Widow’s Son,” at just over 8,300 words, is about twice as long as either “First Kings” or “Hosea,” and its length would make it a difficult placement with literary journals. Once one writes beyond 5,000 words it becomes increasingly difficult to place. I had only just begun to circulate “The Widow’s Son,” to one or two places, when I saw the Wordrunner notice.

Wordrunner responded promptly, and publication was scheduled for December 2020. In the intervening months I continued the work in progress, mainly producing one new piece, “The Buzite.” I mentioned it to Jo-Anne Rosen, the editor with whom I was working at Wordrunner, but I felt trying to include it in the First Kings collection would throw the three pieces out of balance. I think I was right about that, so “The Buzite” is currently making the literary-journal rounds (as is another brand-new, somewhat fragmentary piece, “The Appearance of Horses”).

It has been a wonderfully rewarding experience working with Jo-Anne Rosen and Wordrunner. One issue we discussed has to do with the pieces’ titles, which are obviously derived from the Bible. Yet the connections between the titles and their stories isn’t crystal clear. Jo-Anne was in favor of adding epigraphs to each story in an attempt to connect the dots, so to speak, for readers. I tend to like epigraphs in my books, so I was open to the idea and tried to find some suitable quotes from the Bible. It proved harder than I imagined. I didn’t much like any of the quotes I came up with for their stories, but suggested a compromise whereby we would use one as an epigraph for the collection as a whole. Jo-Anne wisely, and diplomatically, demurred.

The problem, I discovered, is that the biblical associations are deliberately abstract and multifaceted, and trying to pin an epigraph to the stories forced a more limited and more concrete connection. I very much believe in the notion that interpreting a piece of writing is a partnership between writer and reader. When it comes to finding associations between the biblical references and the texts of the narratives, I prefer for readers to have free imaginative rein. I obviously have something in mind, but I believe readers could come up with cleverer and more interesting ideas. It’s one of the joys of reading, after all.

Writing a novel–or any long work, imaginative or otherwise–can be a lonely business. It requires countless hours of being alone, to write, to research, to think, to wonder. I like to have some human contact regarding the work along the way, which is why I send out pieces as a work progresses. The editors who see fit to publish them provide more encouragement than they can know. Wordrunner eChapbooks’ publishing First Kings and Other Stories has provided me a great deal of satisfaction as well as artistic fuel. It will be years yet before the larger work is complete, but all the editors who will have helped it along the way are invaluable to the process and truly appreciated

First Kings and Other Stories is available via Smashwords, Kindle, and at the Wordrunner site. Visit the book’s site at my author page, and access the sell sheet here.

Jailbreak!: William Gass’s Lifelong Work to Free Himself from the Imprisonment of Print

This paper was presented at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture Since 1900, University of Louisville, on February 23, 2018. Due to a last-minute change, I chaired the panel, Temporalities of Revision. Other panelists were Kelly Kiehl, University of Cincinnati; and Sarah-Jordan Stout, Rice University. The paper is dedicated to William H. Gass, who passed away December 6, 2017.

In the annals of American experimental fiction, William H. Gass’s Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife holds a place of reverence due, mainly, to its ambitious (some may say, excessive) experimentation: nineteen different typefaces (varying in point sizes, with unusual placements and movements on the pages), and copious graphic elements, including several photos of a nude model. The odd little novella first appeared in 1968 as TriQuarterly supplement No. 2 – in its most experimental format, which included a variety of paper stock in addition to its other eccentricities – then in a hardcover edition from Knopf (1971) and later a paperback edition from Dalkey Archive (1989). The Knopf and Dalkey editions maintained the original design, minus the use of various paper stock.

Willie Masters’ occupies a place of infamy in Postmodern circles: No one faults Gass’s ambitions. However, the odd little book hasn’t garnered much, well, affection over the years either, which I think is a crying shame. Even Gass himself wasn’t overly generous regarding the end result. In the Art of Fiction interview (1976) he stated,

I was trying out some things. Didn’t work. Most of them didn’t work. . . . Too many of my ideas turned out to be only ideas—situations where the reader says: “Oh yeah, I get the idea,” but that’s all there is to get, the idea. I don’t give a shit for ideas—which in fiction represent inadequately embodied projects—I care only for affective effects. (Conversations 22)

He was, I think, a little too hard on himself. I am moved by the book; it affects me, but perhaps not quite as Gass would have hoped. And Gass may have changed his opinion of Willie Masters’ success over time. In the essay “Anywhere but Kansas” which first appeared in The Iowa Review in 1994 (nearly thirty years after writing Willie Masters’ and on the cusp of The Tunnel’s publication, which required a gestation of nearly that length of time and which makes use of many of the techniques in its infamous predecessor), Gass discusses the importance of experimentation: “An experiment, I would learn much later, . . . had to arise from a real dissatisfaction with existing knowledge. There was a gap to be filled, a fracture to be repaired, an opening to be made” (29). The public at large, he says, only admires experiments that work; however, for the experimenters themselves, an unsuccessful experiment may bring its own kind of success. “In the lab,” writes Gass, “a ‘no’ may not elicit cheers; it is nevertheless a bearer of important information” (30). He may, then, have learned some important narrative lessons from Willie Masters’, lessons he took to heart during the three decades he labored on The Tunnel, which shares some of Willie Masters’ techniques, but significantly toned down.

What is more, three decades later, Gass felt just as strongly about the need for writers to engage in experimentation for the sake of their art: “[I]t is . . . repeatedly necessary for writers to shake the system by breaking its rules, ridiculing its lingo, and disdaining whatever is in intellectual fashion. To follow fashion is to play the pup” (Conversations 30). Gass may not have achieved the aesthetic affects he was aiming for in Willie Masters’ in 1968, but, in retrospect, he seemed to value his own efforts — though he doesn’t say so explicitly.

What is more, three decades later, Gass felt just as strongly about the need for writers to engage in experimentation for the sake of their art: “[I]t is . . . repeatedly necessary for writers to shake the system by breaking its rules, ridiculing its lingo, and disdaining whatever is in intellectual fashion. To follow fashion is to play the pup” (Conversations 30). Gass may not have achieved the aesthetic affects he was aiming for in Willie Masters’ in 1968, but, in retrospect, he seemed to value his own efforts — though he doesn’t say so explicitly.

As wildly experimental as Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife turned out to be, it was tamer than Gass had in mind1. A visit to the Gass Papers at Washington University in St. Louis, where Gass taught philosophy from 1969 to 1999, can give us some sense of what the author had in mind from the start, working only with a manual typewriter, pen or pencil, straight edge, scissors and glue, plus other objects like fabric and newspaper clippings. In part what Gass was trying to achieve was bridging the gap between writer and reader by making the narrative come to life, so to speak, in the reader’s hands. That is, rather than simply describing things — that is, providing symbols for things — which evoke intellectual and (hopefully) emotional responses in the reader, Gass wanted the thing itself to become part of the reader’s world. In essence, the book itself becomes a performance piece in the reader’s world — akin perhaps to the playwright’s task in moving from script to performed play. One writes of a pistol on the page, which becomes a real pistol on the stage, one which discharges so that the audience members can actually hear its bang and actually smell its smoke.

Gass may encourage this comparison by including a play as one of the multiple narratives at work in Willie Masters’, whose overarching narrative is Babs Masters’ seduction of the reader into her lonely text. One of the best examples of Gass’s attempt to move from manuscript into the reader’s reality is via a set of coffee-cup rings that appear on several pages. A new section of the novella begins, “The muddy circle you see just before you and below you represents the ring left on the leaf of the manuscript by my coffee cup” ([37]). But just as the theatrical pistol is only a prop, Gass immediately acknowledges that the dark-brown circle is not actually a ring from his cup: “Represents, I say, because, as you must surely realize, this book is many removes from anything I’ve set pen, hand, or cup to.” The author attempts to enter the reader’s reality more corporeally than authors typically do, but, ultimately, that gap can only be bridged so far.

We can see that the coffee-ring idea was an early one in Gass’s conception of the book, and, in fact, was created no doubt by actual coffee.2 The circle returns later in the novella, but in a more metaphorical role according to the text it encircles: “This is the moon of daylight” ([52]). The circle multiplies to appear as five circles on the final two pages of the book, in two cases highlighting the inserted phrases “HERE BE DRAGONS” and “YOU HAVE FALLEN INTO ART — RETURN TO LIFE” ([58]). The final coffee-like ring appears on the facing page, which is a close-up of the female nude’s breasts and navel, with the ring encircling the latter.3 Others have noted that there are (at least) two female models used for the book: one whose image appears on the cover, and another whose images appear (possibly) eight times throughout the book. The final coffee ring appears on the torso of, it appears, the cover’s model. The interior version of Babs Masters is more, well, voluptuous than the cover and final coffee-ring Babs. Yet there is a striking difference between the cover and the final image: The nude on the cover has no belly-button; it’s been airbrushed out. The final coffee-ring encircles and emphasizes the belly-button, however, maybe making us take note of its absence on the cover.

Is it in fact, then, Babs represented on the cover of the book, or is it Eve? Gass would go on to use Eve as a metaphor with regularity in his fictions. Michael Hardin makes some provocative observations about Willie Masters’ in an article in Short Story, discussing both Gass’s novella and Kathy Acker’s New York City in 1979. Hardin notes, for example, that on the first page of the book Babs’s hand reaches toward the title just as the reader does in a rather hand-of-God sort of way:

The extended arm references Michelangelo’s Creation of Man, where God is extending his hand to spark life into Adam’s extended hand. The reader must decide whether Babs (the wife) is in the space of the creator or the created. . . . [G]iven the nature of the sexual politics of the text, one might argue that Babs is the creative spark passed between author (whose hand reaches out with the pen) and reader, God and Adam. (80-81)

Perhaps Hardin didn’t notice the MIA belly-button because he doesn’t bring Eve into the analysis even though it seems rife for her inclusion. By encircling Babs’s navel at the conclusion of the book (and returning to the cover model for the image), Gass signals that Eve/Babs is now only Babs, making the statement “You have fallen into art—return to life” especially provocative. It may be that our sojourn in the complicated text of Willie Masters’ – which Gass overtly parallels with our having sexual intercourse with Babs – is akin to the Fall, and when we reach the final page we are expelled from the textual Paradise, like hapless Adam and Eve; however, like Adam and Eve we have acquired a unique experience for which we are the richer, even if that richness is colored by sin. But since sin in this metaphor is art/sex, Gass implies sin ain’t such a bad thing, and, in fact, it (art, experiencing it, creating it) is the only thing that makes life worth living: An idea which Gass returned to again and again in his fiction, his essays, his criticism, and his interviews. In addition to being a voracious and eclectic reader, Gass said, in 1971, that he enjoyed “all” the arts, “especially perhaps ballet (when pure and not mucked up) and architecture. I was an opera nut when young. . . . I haunt museums when I can. In one sense, painting has influenced my theory of art more than almost anything, music my practice of it” (9). Gass’s interest in the visual is obviously reflected in his merging of text with pictorial elements. As a writer, he was about what all writers ought to be about, he said: “You are advancing an art—the art. That is what you are trying to do” (26).

Perhaps Hardin didn’t notice the MIA belly-button because he doesn’t bring Eve into the analysis even though it seems rife for her inclusion. By encircling Babs’s navel at the conclusion of the book (and returning to the cover model for the image), Gass signals that Eve/Babs is now only Babs, making the statement “You have fallen into art—return to life” especially provocative. It may be that our sojourn in the complicated text of Willie Masters’ – which Gass overtly parallels with our having sexual intercourse with Babs – is akin to the Fall, and when we reach the final page we are expelled from the textual Paradise, like hapless Adam and Eve; however, like Adam and Eve we have acquired a unique experience for which we are the richer, even if that richness is colored by sin. But since sin in this metaphor is art/sex, Gass implies sin ain’t such a bad thing, and, in fact, it (art, experiencing it, creating it) is the only thing that makes life worth living: An idea which Gass returned to again and again in his fiction, his essays, his criticism, and his interviews. In addition to being a voracious and eclectic reader, Gass said, in 1971, that he enjoyed “all” the arts, “especially perhaps ballet (when pure and not mucked up) and architecture. I was an opera nut when young. . . . I haunt museums when I can. In one sense, painting has influenced my theory of art more than almost anything, music my practice of it” (9). Gass’s interest in the visual is obviously reflected in his merging of text with pictorial elements. As a writer, he was about what all writers ought to be about, he said: “You are advancing an art—the art. That is what you are trying to do” (26).

One of Gass’s ambitions in Willie Masters’ is to seduce the reader into reading the text carefully and thoughtfully – that is, deeply. Already in 1966, when he began work on the novella, Gass recognized that too many readers were impatiently speeding through texts, and (worse perhaps) too many writers were providing them material that enabled such shallow encounters. Gass said, “A lot of modern writers . . . are writing for the fast mind that speeds over the text like those noisy bastards in motor boats. . . . They stand to literature as fast food to food” (25). Whenever one begins unpacking a Gass metaphor, the act, by necessity, becomes reductive. Nevertheless, for illustration’s sake, I’ll work my way through Gass’s attempted seduction of the reader in Willie Masters’ via his use of metaphor, wordplay, and imagery. I will force myself as best I can to hold onto a single strand and resist the text’s Siren song which could lead us in myriad directions (not to our doom, however).

One of several storylines Gass juggles in Willie Masters’ is a playscript featuring Ivan and Olga wherein Ivan finds a penis baked into his breakfast roll. At this point in the novella the carnival ride hasn’t become too topsy-turvy for the reader, but it’s about to begin spinning (nearly) out of control. Gass starts interrupting the playscript with footnotes which engage the reader in academic-sounding notes related, it seems, to the main narrative. The first footnote is signaled by an asterisk, and the second by two asterisks (just as Gass is using asterisks to represent other things in the text besides footnotes, so are these footnotes after all? — Or is Gass toying with us?). The second alleged footnote references John Locke’s Concerning Human Understanding (ha!) and discusses how “ideas” are “take[n] in,” “masticate[d]” and “swallow[ed] down” ([15], my emphasis on down). The footnote-like interruptions continue on the following pages, except on page [17] the footnote itself is interrupted with yet another typeface, in bold, which says, “Now that I’ve got you alone down here [i.e., at the bottom of the page], you bastard, don’t think I’m letting you get away easily, no sir, not you brother; anyway, how do you think you’re going to get out, down here where it’s dark and oily like an alley . . . ?” Suddenly “down here” is not the bottom of the page, but rather it’s Babs talking to us about her dark and oily sex, which she says is as “meaningless as Plato’s cave.” We, the blissful readers, have been lured there, in between Babs’s waiting legs, and there’s no easy way out.

The complexities mount, so to speak, for twenty or more pages before we come (ugh) to the section that introduces us to the “muddy circle” — whose dark shape, like the opening of Plato’s cave perhaps, has even more symbolic weight than mere coffee-cup ring. We also note that the section begins with Babs’s bare leg and foot knocking down the enlarged “T” in “The” with which the paragraph starts, thus echoing the earlier seductive “footnote” ([37]). Gass’s playing with the convention of the footnote, a standard feature of annotated texts, appears to contradict its function, at first, but upon further contemplation (and multiple readings) it does not contradict it. That is, normally a footnote aids in clarifying a reference, and thereby maybe an entire passage, but the footnotes in Willie Masters’ seem to only muddy the narrative waters, obscuring instead of clarifying. However, we later realize that the footnotes are aiding our understanding of the novella as a whole, contributing to the convention that Gass is attempting to seduce us into a complex relationship with his book. Intercourse with Babs Masters cannot be a mere one-night stand; she gets into your head and won’t let you go — à la Fatal Attraction. (Luckily I don’t have a pet rabbit.)

The complexities mount, so to speak, for twenty or more pages before we come (ugh) to the section that introduces us to the “muddy circle” — whose dark shape, like the opening of Plato’s cave perhaps, has even more symbolic weight than mere coffee-cup ring. We also note that the section begins with Babs’s bare leg and foot knocking down the enlarged “T” in “The” with which the paragraph starts, thus echoing the earlier seductive “footnote” ([37]). Gass’s playing with the convention of the footnote, a standard feature of annotated texts, appears to contradict its function, at first, but upon further contemplation (and multiple readings) it does not contradict it. That is, normally a footnote aids in clarifying a reference, and thereby maybe an entire passage, but the footnotes in Willie Masters’ seem to only muddy the narrative waters, obscuring instead of clarifying. However, we later realize that the footnotes are aiding our understanding of the novella as a whole, contributing to the convention that Gass is attempting to seduce us into a complex relationship with his book. Intercourse with Babs Masters cannot be a mere one-night stand; she gets into your head and won’t let you go — à la Fatal Attraction. (Luckily I don’t have a pet rabbit.)

Earlier I said that I am affected by Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife. I must acknowledge that its characters do not engage me on an emotional level, but the book itself – Gass’s ambitions and his achievements –are inspirational to me as a creative writer. A black-and-white photo of the Master hangs on the wall next to my desk; a line drawing, too, on the wall of our master bedroom, next to the door where it will be viewed most frequently; I have acquired 51 books either by Gass or which include his writing (among them first editions, rare books, and several bearing his autograph), and this isn’t counting the books about Gass’s work. I have surrounded myself by the Master and his words, including this literary call-to-arms at the end of Willie Masters’: “It’s not the languid pissing prose we’ve got, we need; but poetry, the human muse, full up, erect and on charge, impetuous and hot and loud and wild like Messalina going to the stews, or those damn rockets streaming headstrong into the stars.”

Amen, Master. Rest in peace, and in the knowledge some of us will carry on the good fight.

Notes

1. See “‘The Text Is Oozing Out’: William H. Gass and Transliteracy” by Clarence Wolfshohl, Studies in Short Fiction, vol. 26, no. 4, 1989, pp. 497-503, in which Wolfshohl shares some of his personal correspondence with Gass regarding Willie Masters’ and its production.: “The stains and the nude photos are as close as Gass comes to bringing the outside physical world into the hook, but he wanted much more. He also thought of having cloth tip-ins and a condom bookmark, and, in his own words, ‘lots of other nutty things.'”

2. I’d like to thank Joel Minor and the other archivists in the Special Collections Department of Olin Library at Washington University in St. Louis for their assistance in examining the manuscript drafts of Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife. Visit William H. Gass: The Soul Inside the Sentence.

3. The photography in Willie Masters’ was by Burton L. Rudman. Gass had hoped for an older model to portray Babs, according to Wolfshohl (see note 1). The images of Gass’s original manuscript pages are by the author.

Works Cited

Gass, William H. “Anywhere but Kansas.” Tests of Time, The U of Chicago P, 2002, pp. 28-36.

—. Conversations with William H. Gass. Edited by Theodore G. Ammon, UP of Mississippi, 2003.

—. Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife, Dalkey Archive, 1998.

Hardin, Michael. “Desiring Fragmented Bodies and Texts: William H. Gass’s Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife and Kathy Acker’s New York City in 1979.” Short Story, vol. 11, no. 2, 2003, pp. 79-90.

Accidental Poets: Paul Valéry’s influence on William Gass

The following paper was presented at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture Since 1900, held at the University of Louisville February 18-20. Others papers presented were “The Poet Philosopher and the Young Modernist: Fredrich Nietzshe’s Influence on T.S. Eliot’s Early Poetry” by Elysia C. Balavage, and “Selections from ‘The Poetic Experiments of Shuzo Takiguchi 1927-1937’” by Yuki Tanaka. Other papers on William H. Gass are available at this blog site; search “Gass.”

In William H. Gass’s “Art of Fiction” interview, in 1976, he declared two writers to be his guiding lights—the “two horses” he was now “try[ing] to manage”: Ranier Maria Rilke and Paul Valéry. He added, “Intellectually, Valéry is still the person I admire most among artists I admire most; but when it comes to the fashioning of my own work now, I am aiming at a Rilkean kind of celebrational object, thing, Dinge” (LeClair 18). That interview for The Paris Review was exactly forty years ago, and viewing Gass’s writing career from the vantage point of 2016, I am here to suggest that, yes, Rilke has been a major influence, but Valéry’s has been far greater than what Gass anticipated; and in fact may have been even greater than Rilke’s in the final analysis. Assessing influence, however, is complicated in this case, I believe, because a large part of Gass’s attraction to Valéry’s work in the first place was due to his finding the Frenchman to be a kindred spirit. Hence it is difficult to say how much of Gass is like Valéry because of Valéry’s influence and how much is because of their inherent like-mindedness.

A quick survey of Gass’s work since 1976—which includes two novels, a collection of novellas, a collection of novellas and stories, and eight books of nonfiction—may imply that Rilke has been the greater influence, as Gass intended. After all, Gass’s magnum opus, The Tunnel (1995), for which he won the American Book Award, centers on a history professor of German ancestry who specializes in Nazi Germany (Rilke allusions abound); and his other post-1976 novel, Middle C (2013), for which he won the William Dean Howells Medal, centers on a music professor born in Vienna whose special interest is Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg; and, glaringly, there is Gass’s Reading Rilke (1999), his book-length study of the problems associated with translating Rilke into English. However, a more in-depth look at Gass’s work over these past four decades reveals numerous correspondences with Valéry, some of which I will touch upon in this paper. The correspondence that I will pay particular attention to, though, is that between the title character of Valéry’s experimental novella The Evening with Monsieur Teste (1896) and the protagonist of Gass’s Middle C, Joseph Skizzen.

Before I go further, a brief biographical sketch of Paul Valéry: He was born in 1871, and published two notable works in his twenties, the essay “Introduction to the Method of Leonardo da Vinci” and Monsieur Teste; then he stopped publishing altogether for nearly twenty years—emerging from his “great silence” with the long poem “The Young Fate” in 1917 at the age of forty-six. During his “silence,” while he didn’t write for publication, he did write, practically every day, filling his notebooks. Once his silence was over, he was catapulted into the literary limelight, publishing poems, essays, and dramas, becoming perhaps the most celebrated man of letters in France. By the end of his life in 1945 he’d been nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature a dozen times.

The title for this paper comes from Gass himself. In his 1972 review of Valéry’s collected works, in the New York Times Book Review, he wrote that Valéry “invariably . . . [pretended] he wasn’t a poet; that he came to poetry by accident” (The World Within the Word 162). By the same token, Gass has insisted in numerous interviews (and he’s given many, many interviews) that he’s not a poet, that the best he can achieve is an amusing limerick. Others, however, have asserted that Gass’s fiction is more akin to poetry than prose, that his novellas and novels are in essence extremely long prose poems; and in spite of his insistence on his not being a poet, he would seem to agree with this view of his work. In a 1998 interview, for instance, Gass said, “I tend to employ a lot of devices associated with poetry. Not only metrical, but also rhyme, alliteration, all kinds of sound patterning” (Abowitz 144). Moreover, about a decade earlier he said that “all the really fine poets now are writing fiction. I would stack up paragraphs of Hawkes, Coover, Elkin, or Gaddis against the better poets writing now. Just from the power of the poetic impulse itself, the ‘poets’ wouldn’t stand a chance” (Saltzman 91). Critics have tended to include Gass in the group of writers whom Gass described as poet-novelists.

For your consideration, from The Tunnel:

A smile, then, like the glassine window in a yellow envelope. I smiled. In that selfsame instant, too, I thought of the brown, redly stenciled paper bag we had the grocer refill with our breakfast oranges during the splendid summer of sex and sleep just past—of sweetly sweating together, I would have dared to describe it then, for we were wonderfully foolish and full of ourselves, and nothing existed but your parted knees, my sighs, the torpid air. It was a bag—that bag—we’d become sentimental about because (its neck still twisted where we held it) you said it was wrinkled and brown as my balls, and resembled an old cocoon, too, out of which we would both emerge as juicy and new as the oranges, like “Monarchs of Melody,” and so on, and I said to you simply, Dance the orange (a quotation from Rilke), and you said, What? There was a pause full of café clatter. (160-61)

And beyond Gass’s poetic prose, he has written actual poems, besides the off-color limericks that populate The Tunnel. In Middle C, for example, there is a longish, single-stanza poem written via the persona of the protagonist, Joseph Skizzen. It begins, “The Catacombs contain so many hollow heads: / thighbones armbones backbones piled like wood, / some bones bleached, some a bit liverish instead: / bones which once confidently stood / on the floor of the world” (337). And, perhaps more significantly, there are the translated poems in Reading Rilke. There was a celebration held at Washington University in St. Louis in honor of Gass’s ninetieth birthday, Passages of Time, and he read from each of his works in chronological order, except he broke chronology to end with his translation of Rilke’s “The Death of the Poet,” which concludes,

Oh, his face embraced this vast expanse,

which seeks him still and woos him yet;

now his last mask squeamishly dying there,

tender and open, has no more resistance,

than a fruit’s flesh spoiling in the air. (187)

It was a dramatic finale, especially since the event was supposed to be in July, near Gass’s birthday, but he was too ill to read then; so it was rescheduled for October, and the author had to arrive via wheelchair, and deliver the reading while seated. Happily, he was able to give another reading, a year later, when his new book, Eyes, came out. (I wasn’t able to attend the Eyes reading, so I’m not sure how he appeared, healthwise, compared to the Wash U. reading.)

My point is that, like Valéry, Gass has downplayed his abilities as a poet, yet his literary record begs to differ. The fact that he broke the chronology of his birthday celebration reading to conclude with a poem—and he had to consider that it may be his final public reading, held on the campus where he’d spent the lion’s share of his academic life—suggests, perhaps, the importance he has placed on his work as a poet, and also, of course, it may have been a final homage to one of his heroes. In spite of Gass’s frailness, his wit was as lively as ever. When he finished reading “The Death of the Poet,” and thus the reading, he received an enthusiastic standing ovation. Once the crowd settled, he said, “Rilke is good.”

Evidence of the earliness of Valéry’s influence or at least recognized kinship is the preface to Gass’s iconic essay collection Fiction and the Figures of Life (1970), which Gass devotes almost entirely to the connection between the collection’s contents and the way that Valéry had assembled his oeuvre. Gass writes, “It is embarrassing to recall that most of Paul Valéry’s prose pieces were replies to requests and invitations. . . . [H]e turned the occasions completely to his account, and made from them some of his profoundest and most beautiful performances” (xi). Gass continues, “The recollection is embarrassing because the reviews and essays gathered here are responses too—ideas ordered up as, in emergency, militias are”; and then he describes his book as a “strange spectacle” in which he tries “to be both philosopher and critic by striving to be neither” (xii). So, Gass recognizes the parallel between the forces at work in Valéry’s literary life and his own. Gass has readily acknowledged the slowness with which his fiction has appeared (notably, it took him some twenty-six years to write The Tunnel), citing two reasons: the slowness with which he writes, and rewrites, and rewrites; but also the fact that he regularly received opportunities to contribute nonfiction pieces to magazines and anthologies, and to give guest lectures, and they tended to pay real money, unlike his fiction, which garnered much praise but little cash over his career.

This parallel between the circumstances of their output is interesting; however, the correspondences between Valéry’s creative process and his primary artistic focus, and Gass’s, is what is truly significant. In his creative work, Valéry was almost exclusively interested in describing the workings of the mind, of consciousness; and developing complex artistic structures to reflect those workings. T. S. Eliot noted Valéry’s dismissiveness of the idea of inspiration as the font of poetic creation. In Eliot’s introduction to Valéry’s collection The Art of Poetry, he writes, “The insistence, in Valéry’s poetics, upon the small part played [by ‘inspiration’ . . .] and upon the subsequent process of deliberate, conscious, arduous labor, is a most wholesome reminder to the young poet” (xii). Eliot goes on to compare Valéry’s technique and the resulting work to that done by artists in other media, most notably music composers: “[Valéry] always maintained that assimilation Poetry to Music which was a Symbolist tenet” (xiv). James R. Lawler echoes Eliot when he writes that Valéry “makes much of the comparison of poetry to the sexual act, the organicity of the tree, the freedom of the dance, and the richness of music—especially that of Wagner” (x).

The wellspring of music composition as a source of structural principles for poetry (or highly poetic prose) is arguably the greatest correspondence between Valéry as artist and Gass as artist. Examples abound, but The Tunnel and Middle C offer the most radiant ones. For the The Tunnel Gass developed a highly synthetic structure based on Arnold Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School’s musical theory of a twelve-tone system. Consequently there are twelve sections or chapters, and in each Gass develops twelve primary themes or images. He said, “[T]hat is how I began working out the way the various themes come in and out. It’s layered that way too. . . .” (Kaposi 135). In The Tunnel, Gass’s methodology is difficult to discern because Gass gave it a “chaotic and wild” look while in fact it is, he said, “as tightly bound as a body in a corset” (134). He achieved the appearance of chaos by “deliberately dishevel[ing]” the narrative with “all kinds of other things like repetitions [and] contradictions.” He said, “[T]he larger structure must mimic human memory, human consciousness. It lies, it forgets and contradicts. It’s fragmentary, it doesn’t explain everything, doesn’t even know everything” (134). For Middle C, the use of the Schoenberg system is much more overt, with Skizzen, its protagonist, being a music professor whose specialty is Schoenberg and Skizzen’s obsession with getting a statement about humans’ unworthiness to survive just right. Skizzen believes he is on the right track when he writes the sentence in twelve beats, and near the end of the novel he feels he has the sentence perfect:

First Skizzen felt mankind must perish

then he feared it might survive

The Professor sums up his perfect creation: “Twelve tones, twelve words, twelve hours from twilight to dawn” (352). Gass, through his narrator, does not discuss the sentence’s direct correlation to the Second Viennese School’s twelve-tone system, but it does match it exactly.

Let me return to another Valéry-Gass correspondence which I touched on earlier: their concern with the workings of the mind or, said differently, consciousness. Jackson Mathews, arguably the most herculean of Valéry’s translators into English, begins his introduction to Monsieur Teste with the statement that “Valéry saw everything from the point of view of the intellect. The mind has been said to be his only subject. His preoccupation was the pursuit of consciousness, and no one knew better than he that this pursuit led through man into the world” (vii). Valéry’s interest in the mind was present in his earliest published work, the essay on Leonardo’s method and, even more obviously, Monsieur Teste, that is, “Mr. Head” or “Mr. Brain as Organ of Observation” or something to that effect. However, it was during Valéry’s twenty-year “silence” that he delved into the phenomenon of consciousness most critically. Gass writes, “Valéry began keeping notebooks in earnest, rising at dawn every day like a priest at his observances to record the onset of consciousness, and devoting several hours then to the minutest study of his own mind” (“Paul Valéry” 163). As noted earlier, Gass fashioned The Tunnel, all 800 or so pages of it, to mimic the human mind in its intricate workings. In Middle C, Gass pays much attention to Skizzen’s thought processes, especially his copious writing, revising, critique of, and further revising of his statement about humans’ unworthiness for survival. Such concerns are everywhere in Gass’s work, including his most recently published, the collection of novellas and stories, Eyes. I would point in particular to the novella Charity, a challenging stream-of-consciousness narrative, all a single paragraph, that mercilessly bounces between the main character’s childhood and his present, and, chaotically, various times in between, all the while sorting through his feelings about the act of charity and how he came to feel about it as he does in the now of the story.

In the limited time remaining, I’ll turn to the correspondence between Valéry’s character Monsieur Teste and Gass’s Joseph Skizzen (though I think William Kohler, the narrator of The Tunnel, has significant Teste-esque qualities as well). The convention of The Evening with Monsieur Teste is that the narrator is a friend of Edmond Teste’s, and he goes about attempting to describe his friend’s character. There is very little action per se, and as such almost nothing in the way of plot, in a conventional sense at least (very Gassian in that regard). He tells us that he came to “believe that Monsieur Teste had managed to discover laws of the mind we know nothing of. Certainly he must have devoted years to his research” (11). In Middle C, Joseph Skizzen is obsessed with what he calls his Inhumanity Museum, essentially a record, largely in the form of newspaper clippings and personal notes, of humans’ ceaseless cruelty to one another. The collection is associated with his ongoing struggle to word just so his statement about humans’ unworthiness to survive. Monsieur Teste becomes almost a recluse, desiring little contact with other people. He is married, but the narrator suggests that Monsieur and Madam Teste’s relationship is more platonic than passionate, due to Edmond’s preference for the intellectual over the emotional. Similarly, Skizzen never marries in Middle C, and in fact never has sex—he flees as if terrified at the two attempts to seduce him, both by older women, in the novel. Ultimately he ends up living with his mother in a house on the campus where he teaches music history and theory, his few “pleasures” consisting of listening to Schoenberg, assembling his Inhumanity Museum, and revising his pet statement. What is more, Teste’s friend describe Edmond’s understanding of “the importance of what might be called human plasticity. He had investigated its mechanics and its limits. How deeply he must have reflected on his own malleability!” (11-12). Skizzen’s malleability is central to his persona in Middle C. He goes through several name changes, moving from Austria to England to America, and eventually fabricates a false identity, one which includes that he has an advanced degree in musical composition, when in fact his knowledge of music is wholly self-taught. One of the reasons he gravitates toward Schoenberg as his special interest is because of the composer’s obscurity and therefore the decreased likelihood that another Schoenberg scholar would be able to question Skizzen’s understanding of the Austrian’s theories. But over time Skizzen molds himself into a genuine expert on Schoenberg and a respected teacher at the college—though his fear of being found out as a fraud haunts him throughout the novel.

To utter the cliché that I have only scratched the surface of this topic would be a generous overstatement. Perhaps I have eyed the spot where one may strike the first blow. Yet I hope that I have demonstrated the Valéry-Gass scholarly vein to be a rich one, and that an even richer one is the Valéry-Rilke-Gass vein. A couple of years ago I hoped to edit a series of critical studies on Gass, and I put out the call for abstracts far and wide; however, I had to abandon the project as I only received one email of inquiry about the project, and then not even an abstract followed. Nevertheless, I will continue my campaign to bring attention to Gass’s work in hopes that others will follow me up the hill, or, better still, down the tunnel. Meanwhile, if interested, you can find several papers on Gass’s work at my blog.

Works Cited

Abowitz, Richard. “Still Digging: A William Gass Interview.” 1998. Ammon 142-48.

Ammon, Theodore G., ed. Conversations with William H. Gass. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2003. Print.

Eliot, T. S. Introduction. The Art of Poetry. By Paul Valéry. Trans. Denise Folliot. New York: Pantheon, 1958. vii-xxiv. Print.

Gass, William H. Charity. Eyes: Novellas and Short Stories. New York: Knopf, 2015. 77-149. Print.

—. Preface. Fiction and the Figures of Life. 1970. Boston, MA: Nonpareil, 2000. xi-xiii. Print.

—. Middle C. New York: Knopf, 2013. Print.

—. Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation. 1999. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

—. The Tunnel. 1995. Champaign, IL: Dalkey Archive, 2007. Print.

—. The World Within the Word. 1978. New York: Basic Books, 2000. Print.

Kaposi, Idiko. “A Talk with William H. Gass.” 1995. Ammon 120-37.

Lawler, James R. Introduction. Paul Valéry: An Anthology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1977. vii-xxiii. Print.

LeClair, Thomas. “William Gass: The Art of Fiction LXV.” 1976. Ammon 46-55. [online]

Mathews, Jackson. Introduction. Monsieur Teste. By Valéry. Trans. Jackson Mathews. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1989. vii-ix. Print.

Valéry, Paul. Monsieur Teste. 1896. Trans. Jackson Mathew. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1989. Print.

Notes on images: The photo of Paul Valéry was found at amoeba.com via Google image. The photo of William H. Gass was found at 3ammagazine.com via Google image.

Fictionalizing the Life and Voice of Washington Irving

The following paper — “Fictionalizing the Life and Voice of Washington Irving” — was presented at the North American Review Bicentennial Conference at the University of Northern Iowa, in Cedar Falls, which ran from June 11 to 13, 2015. This paper was part of the “Voice and Point of View” panel on June 13. Other papers presented were “Expanding the Powers of First-Person Narration” by Buzz Mauro and “The Art of Narrative Telling: Transforming Cheever’s Voice” by Grant Tracey. In addition to presenting, I also moderated the panel.

I’m here today to talk about writing my novel An Untimely Frost, which I worked on between about 2006 (I think) and 2011, eventually publishing it via my own press, Twelve Winters, in 2014—Twelve Winters Press, by the way, has a table at the conference. The inspiration for the novel was Washington Irving’s rumored courtship of Mary Shelley. It seemed to me that a romantic relationship between the author of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and the author of Frankenstein could make for an intriguing chemistry. I didn’t know where or when I’d learned of that rumor, and I wasn’t especially interested in verifying its accuracy because I decided very early on that I wasn’t going to write a fictionalized biography of Irving and Shelley and their time together. Rather, I was going to use them as sources of inspiration and an armory of period details as needed. [As noted, I didn’t research the actual relationship between Irving and Shelley when writing the novel; however, in preparing this talk I came across this rare book—The Romance of Mary W. Shelley, John Howard Payne and Washington Irving (1907)–which would be of interest to anyone who wanted to know more about the famous authors’ “romance.”]

For an earlier project, which resulted in the novella Weeping with an Ancient God, I wrote a fictionalized biography of author Herman Melville’s real-life experiences among cannibals in 1842. I was dedicated to staying true to the established details of Melville’s life and times, which made for a challenging artistic endeavor. I like to believe that the novella turned out pretty well, but oftentimes I did feel hemmed in by reality and by Melville’s biography. Not to mention, real life rarely provides us with a satisfying narrative arc, which tends to handicap a novelist. It’s a bit like running in a three-legged race. It’s an experience all its own, but there’s no helping that the entire time one is keenly aware of how much easier it would be to race the usual two-legged way.

Thus, when I began writing about Irving and Shelley, I had no intention of shackling my creativity to their real lives. I began by concocting fictional names for them, eventually ending up with “Jefferson Wheelwright” and “Margaret Haeley.” I also decided early on that Jefferson Wheelwright would be my first-person narrator. I obviously had some familiarity with Washington Irving—and I’d taught “Sleepy Hollow” a couple of times in a college course—but I didn’t feel that I knew him and, more importantly, his voice well enough to create my Jefferson Wheelwright persona. To prepare, I did read several biographical sketches of Irving and more of his fictional stories. However, what I really wanted to steep my brain in was his real-life speaking voice, and the closest I could come to that, given that he lived in the early and mid nineteenth century, was to study his published letters.

I got hold of two collections in particular, both edited by Stanley T. Williams. One collection, brought out by Harvard University Press, concerns Irving’s letters “from England and the Continent, 1821-1828,” and the other, brought out by Yale University Press, consists of his letters “from Sunnyside and Spain,” spanning the years 1840-1845. I made use of both collections, and in fact one of the epigraphs for the novel comes from a Madrid 1842 letter. However, I found the letters from the earlier period to be more helpful since they correspond more closely to the time frame and the geography of my novel’s setting.

I culled the letters, along with biographical information, for two sorts of material. First, while I wasn’t writing a fictionalized biography based on Irving’s life, I was open to transferring and transforming real-life details from Irving to my creation, Wheelwright. Second, and more vital, I wanted to capture as nearly as possible Irving’s narrative style.

Without reading through the biographical notes and letters in their entirety again, it’s difficult for me to recall all that I borrowed in terms of real-life details and events. I did skim through the letters in preparation for this presentation, and I was surprised in a couple of instances regarding details that in my recollection I had wholly made up, but in actuality stemmed from my research.

One of the character details that I know I extracted from Irving’s letters had to do with a skin condition of his legs and feet that plagued him in the 1821-28 period. For instance, he writes from Germany on August 20, 1822: “I grew very lame in trudging about the dutch [sic] towns, and unluckily applied a recipe given me by old Lady Liston (may god bless her, and preserve her from her own prescriptions!)—it played the vengeance with me [. . .] I could scarcely put my feet to the ground & bear my weight upon them [. . .]” (“Wi[e]sbaden” 19). Elsewhere Irving talks about seeking treatment from various physicians. I decided early on in the writing process that some sort of foot condition would be part of my Jefferson Wheelwright’s situation. I guess I vaguely thought it might have some metaphorical value, connecting to his fear that he was not evolving, not moving forward, as a writer and artist. In An Untimely Frost, Wheelwright requests the aid of a London physician, Dr. Carter. In Chapter 2, I write,

On the first morning, he listened to my complaint while touching and gently kneading my feet and toes, which were blotchy red, except around the toenails where the skin was a vibrant purple. Spots on my feet were pained to the touch while my toes were dead numb. [. . .] The good doctor said it was a circulation problem; he said that even though exercise irritated my feet, rest was counterproductive, that we must increase the blood flow to nourish the nerve fibers.” (11)

In reality, Irving was laid up for days and even weeks with bouts of his “cutaneous condition,” but I didn’t think that would make for an especially exciting narrative, to have Jefferson Wheelwright lying around his hotel room for days on end nursing his feet, so I had Dr. Carter prescribe exercise. Carter becomes an important character in the novel—although when I first introduced him in the second chapter I had no idea whether it would be a cameo appearance or lead to a larger role.

In addition to physical details I also borrowed one of Washington Irving’s personality traits, namely his lack of interest and acumen when it came to business affairs. He let his elder brothers manage the family’s business interests, while he focused on his literary aspirations. In my novel, I write:

So far I was having a splendid time lounging in the gigantic bed at The Saint Georges [hotel], drinking the black-black Italian coffee, and scribbling my tale. I even felt a brief—brief, mind you—pang of guilt at the idea that this is what I did to earn my keep in the world. Like many of the Wheelwright men, I’d tried my hand at business, but to dismal results. I simply do not have a head for numbers and inventories and so on—I can conjure whole worlds with my pen, yet adding a column of numbers and arriving at the correct result seemed beyond me (I believe because midway I would lose interest and begin daydreaming of haunted castles on lonely, wind-swept cliffs). (10)

There were numerous details from Irving’s life, especially his writing life, that I commandeered for my purposes, but even more important was capturing Irving’s narrative style—and in particular the style he used in his letters to friends and family, which was somewhat different, on the whole, than his published authorial voice, such as in The Sketch Book and Bracebridge Hall stories.

I wrote a brief essay about trying to capture Irving’s voice for Glimmer Train Press’s Writers Ask series (it appeared in number 54 and I reprinted it in An Untimely Frost). Since it is brief and to the point at hand, I would like to insert it here in its entirety:

Like the vast majority of writers who have come out of a university creative writing program, I was taught to write contemporary literary fiction. However, for over a decade now, I’ve been mainly attracted to historically based narrative, both as a reader and as a writer. When we think of writers tackling a story or novel set in another time and another place, we imagine them doing extensive research on things like people, on the chronology of events, on various aspects of the material world they are attempting to fabricate—and we tend to imagine rightly. For me, though, there is another sort of research that must go on as well, the results of which are not as easy to spot in a story as, say, an infamous assassination or an obsolete gadget; and that is researching the structure of language itself. It can be a nebulous term, but what I’m most interested in is a setting’s voice.

Voice should contribute to the ring of authenticity, to be sure, but, more than that, voice can actually compel the movement of the narrative; voice can shape its structure. William H. Gass spoke to this phenomenon in a 1976 interview for The Paris Review, saying that “word resemblance leads you on [as a writer], not form. So you’ve really got a musical problem, certain paragraphs you are arranging, and you imagine you are orchestrating the flow of feelings from one thing to another.” Gass summed up by saying, “Once you get your key signature, the theme inherent in the notes begins to emerge: the relationship between art and life and all that.” Gass, author of some of the most admired books in the English language, suggests that the physical structure of the words on the page—and the meanings, feelings, moods that they convey—help guide the writer to, essentially, everything else in the narrative: plot development, characterization, theme, setting. . . .

The importance of this sort of research in historically based fiction is nicely illustrated in Charles Frazier’s highly acclaimed novel Cold Mountain, which is set in Civil War-era Appalachia. In an interview available online, Frazier said, “I wanted the language of the book to create a sense of otherness, of another world, one that the reader doesn’t entirely know.” Frazier did library research regarding the material world he was creating, finding “words for tools and processes and kitchen implements that are almost lost words.” Beyond that, however, he was interested in “getting a sense of the particular use of language in that region, the rhythm of it.” Frazier culled period letters and diaries for much of his information, but he also had the benefit of having actually heard “that authentic Appalachian accent” when he was a child.

For my own writing I’ve been attracted to more distant times and places, and as such have not had the benefit of hearing period speakers so printed examples of voice have been my guideposts. Nevertheless, the feel and rhythm of the language can filter into one’s writing by paying attention to the linguistic structures. For my current project I’ve been creating a first-person narrator based on the American author Washington Irving. It isn’t a fictionalized biography. It’s more that Irving’s persona has been the primary inspiration for my protagonist. When I first became interested in the project, I tracked down an obscure collection of Irving’s letters that he wrote between 1821 and 1828. The book has been invaluable to me in my effort to develop an effective narrative voice.

Simply put, in Irving’s day a well-read New Englander structured the language in ways that sound quite foreign—quite exotic even—to us now. Take, for example, this letter written at “Beycheville,” France, October 17, 1825:

I have had something of a dull bilious affection of the system which has clung to me for more than two weeks past. . . . The greater part of Mrs Guestiers household, who have lately removed here, are unwell—I have tried to shake off my own morbid fit by exercise—I have been out repeatedly hunting, as there were two packs of hounds in the neighborhood, but though I have taken violent exercise I do not feel yet reinstated by it. (50)

The terms are spectacular, yes—heaven help anyone who contracts “a dull bilious affection” and Irving’s reference to “violent exercise” makes me think of junior high P.E. class—but even more meaningful to my eye and ear are the syntactic rhythms. Today one might say, “I’ve been feeling sick for a couple of weeks,” but for Irving the “affection of the system” has “clung” to him “for more than two weeks past.” The structure implies that his sense of unwell-being is a sort pernicious companion of whom he can’t quite rid himself, in spite of his taking “violent exercise”—giving the act of exercise a physicality, as if it were an item from the apothecary’s pantry.

Yet I have no particular interest in my protagonist’s contracting a bilious affection or partaking of violent exercise. Rather I want the structure of the language. I want to tell my own tale, but I want to form the sentences as Irving might have had he written of the same events nearly two centuries ago. I normally keep the book of Irving’s letters on my nightstand, and every so often I open to a random page and read awhile, perhaps a few pages but often as little as a sentence or two, because I’m not searching for information: I want to keep retracing the sentence rhythms in my brain, like wagon wheels along a worn track, so that when I sit down to write, the words flow as naturally in the direction of his prose style as if he (or someone like him) were composing them himself. (I must go now—I feel the onset of a bilious affection.)

There haven’t been a lot of reivews of the novel, and the ones that have appeared are somewhat mixed—but the reviewers seem to appreciate the narrative voice that I was able to create. For example, Anne Drolet writes in the North American Review: “Morrissey styles Wheelwright’s voice after the patterns and idioms of 19th-century British speech, and that choice lulls the reader into the historical setting” (47). I presume being lulled into a setting is better than being jarred into one. Cécile Sune says in her blog Book Obsessed: “The writing is beautiful and elaborate, and is a testament to the research Ted Morrissey conducted for this book . . . As a result, it feels like a Victorian novel”—ultimately, though, she only gave it three out of five stars on Amazon (damn it). And most recently William Wright writes for the Chicago Book Review: “There are moments of true brilliance in An Untimely Frost. It reads like it was written by a post-modernist emulating Henry James [I like that line], which proves to be an intriguing combination”—but Wright concludes with “Perhaps with more ruthless editing, the novel could have been a triumph. As it stands, it was a wonderful idea that wasn’t quite pulled off.”

I’ll tell you what, critics are hard to please.

My five years floating around in the fictional consciousness of Washington Irving was an interesting artistic experiment, and it really stretched me as a writer. When I finished with the novel, I began writing a series of interconnected short stories—each in third-person, with shifting points of view, and set for the most part in an unnamed Midwestern village in the 1950s. I finished the twelfth and final story just a few weeks ago, and eventually I’ll be bringing them out in a collection titled Crowsong for the Stricken. I’m considering other long-term writing projects at the moment, and one idea is to return to nineteenth-century London, but not Jefferson Wheelwright. Never say never, but I believe I’ve said all I care to say in the voice and persona of Mr. Wheelwright.

Works Cited

Drolet, Anne. Rev. of An Untimely Frost, by Ted Morrissey. North American Review Fall 2014 (299.4): 47. Print.

“An Interview with Charles Frazier.” BookBrowse [c. 1997]. Web. 9 June 2015.

Morrissey, Ted. An Untimely Frost. Sherman, Ill.: Twelve Winters Press, 2014. Print.

—-. “Researching the Rhythms of Voice.” Writers Ask #54. Portland, Ore.: Glimmer Train Press. Print.

Sune, Cécile. Rev. of An Untimely Frost, by Ted Morrissey. Book Obsessed 10 Oct. 2014. Web.

Williams, Stanley T., ed. Letters from Sunnyside and Spain by Washington Irving. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1928. Print.

—-. Washington Irving and the Storrows: Letters from England and the Continent, 1821-1828. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1933. Print.

Wright, William. “A Hot and Cold ‘Frost.’” Rev. of An Untimely Frost, by Ted Morrissey. Chicago Book Review 18 May 2015. Web.

(Note that the portrait of Washington Irving was obtained via Wikipedia at this link.)

The Celibacy of Joseph Skizzen and the Principles of “On Being Blue”

The following paper was presented at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture Since 1900, Feb. 26-28, 2015, as part of the panel “Sexual Manners,” chaired by Mariah Douglas, University of Louisville. Other papers presented were “‘A world of bottle-glass colours’: Defining Sexual Manners in Subversive Spaces,” by Bonnie McLean, Marquette University; and “Sex as Border Crossing in Anglophone Labanese Fiction,” by Syrine Hout, American University in Beruit. For other Gass papers at this blog, search “gass.”

The Celibacy of Joseph Skizzen and the Principles of On Being Blue