Beauty Must Come First: The Short Story as Art Made of Language

[This paper was presented at the 16th International Conference on the Short Story in English, held June 20-24, Singapore. It was part of the panel “The Short Story and the Aesthetics of Narration.” Other papers were “A Lot Like Joy: Fractured fragments represented within a composite narrative” by Sarah Giles, and “‘Writing back’—The Sideways Progress of Ideasthetic Imagining” by Julia Prendergast.]

“A second rate writer has no reason to exist unless he is on his way to being a first rate writer, and there is no point at all in doing pleasant easy things, or altering one’s conception of how a story ought to be to get it into print” (Saltzman, “Selected Correspondence” 66).

William H. Gass wrote this statement in a letter, in 1958, to an editor who was considering publishing his fiction, which would have been its first appearance in print. The editor was balking at Gass’s elaborate prose style. Gass, age 34 at the time, preferred to remain unpublished than have his words changed. It was an attitude he maintained – that to be edited was to be rejected – throughout what became a long and illustrious career that claimed numerous awards and distinctions, including Pushcart Prizes, Best American Stories, an O. Henry, the PEN/Nabokov Award, the American Book Award, and the William Dean Howells Medal. Gass – novelist, novella-ist, story-writer, critic, translator, and teacher – passed away in 2017 at the age of 93, working on his final project until he no longer had the energy to continue.

This paper is about Gass’s aesthetic theories when it came to producing narrative, and specifically fiction. Luckily, Gass was a generous granter of interviews, so we have a substantial amount of material in which he discusses his ideas about plot, character, setting, theme, symbolism … all of the elements we associate with storytelling (we have printed material, plus video and audio recordings that are available online). He also wrote numerous “craft” essays in which he goes into detail about his writing, as well as the writing techniques of others (among them Henry James, James Joyce, and Gertrude Stein). Such essays were included in his nine nonfiction collections, beginning with Fiction and the Figures of Life (1970) and concluding, for now, with Life Sentences (2012). And we have copious letters, which are carefully archived at Washington University in St. Louis.

To be clear, Gass’s theories are not designed to make one popular, that is, to make one a bestselling author. On the contrary, Gass never achieved that brand of success. In fact, he said (in another letter to the same editor, Charles Shattuck): “[S]uccess is merely failure at another level” (Saltzman 65), by which he meant that a writer must compromise their artistic principles in order to gain the public attention and financial rewards we (in the United States at least) usually associate with literary success. Gass’s primary goal was to create a work of literary art that he himself was satisfied with; if he had secondary goals they were to earn the respect of writers he admired, and to be read beyond his own lifetime. “I don’t write for a public,” Gass said. “[. . .] It’s the good book that all of us are after. I’ve been fortunate in that I think I have the respect of the writers whom I admire” (Saltzman, “Language and Conscience” 24). He did indeed as his work was praised by authors such as John Barth, Susan Sontag, John Gardner, Stanley Elkin, Joy Williams, and William Gaddis, who called Gass “our foremost writer, a magician with language” (Gaddis 629).

Regarding the goal of having his work read beyond his lifetime, it’s been my mission to make that a reality for more than a decade, during which time I’ve been “preaching the Gass-pel” (an expression coined by one of my students that I immediately filched). I’ve presented dozens of conference paper (all available at my blog, and some elsewhere); I’ve included readings of Gass’s work in my book Trauma Theory as an Approach to Analyzing Literary Texts (2021 edition); and I organized the website thetunnelat25.com, an online symposium devoted to Gass’s magnum opus. In my teaching I regularly place Gass’s books on my syllabi, and I share pearls of his writing wisdom with my students regularly (they may say obsessively). Many of these pearls I also share via social media in the form of memes that I’ve created. Like this one:

[This meme has to do with a topic I’ve recently written about: “To Plan or Not to Plan,” available here.]

And this:

[During the presentation I talked briefly about the inherent problem of writing workshops or writing groups: No matter how well-intentioned, peers’ critiques are oftentimes wrongheaded, and an offhanded criticism can send the unwary writer down a frustrating and fruitless rabbit hole. Instead, writers must accept the unavoidable subjectivity of reader response and stay true to their artistic vision.]

And this:

[I felt this was an especially apropos sentiment to share since the conference was comprised of writers from across the globe — but mainly Asia, Australia and Europe — who compose in English, even though for many it’s not their first language.]

I want to touch on some specific ideas Gass had about writing narrative, but before we get there I’m inclined to discuss the cornerstone of his aesthetic philosophy – as well as my primary focus here: Throughout his long writing career, Gass’s main interest was language, and he sought to use it as a painter uses paint, a sculptor uses marble or metal, a composer uses musical notes, or a photographer uses light and shadow. He stated, in a 1976 interview, “As a writer I only have one responsibility, and that’s to the language I’m using and to the thing I’m trying to make” (Duncan 53). He elaborated elsewhere, “Old romantic that I am, I would like to add objects to the world worthy of love. . . . My particular aim is that it be loved because it is so beautiful in itself, something that exists simply to be experienced. So the beauty has to come first” (LeClair 48).

Allow me to restate Gass’s central tenet: The beauty of the language must come first. By extension, then, everything else – all the other elements associated with fictional narrative, plot, characterization, setting, etc. – are subordinate to the quality of the language, to the beauty of the language. Gass’s devotion to beautiful language took many forms. For example, he regularly employed literary devices we normally associate with poetry: alliteration, assonance, rhyming, repetition. As such, Gass considered himself a stylist, meaning that his main interest was the writing itself. “I’ve always been interested in writing as writing. My interest in the various forms is dominated by an interest in style as such” (Duncan 64). Though Gass considered himself an abysmal poet, his use of poetic language was, he said, “compulsive” and “turns up in almost every line of prose, in sound patterns that get pushy, even domineering” (“Retrospection” 43-44).

Gass’s drive to create art made of language led him away from using narrative elements in traditional ways. Mind you, not ways that are utterly unique – I’m a supporter of Adorno’s assertion that when it comes to art, there is nothing new under the sun, yet the true artist must strive for the new nevertheless – but ways that are certainly unusual in modern American fiction, especially popular fiction. For instance, we normally think of characters in fiction as people, or possibly animals or machines (generally, though, personified animals or machines). However, for Gass a character was “any linguistic location of a book toward which a great part of the rest of the text stands as a modifier” (LeClair 53). Gass’s ideas about characters and characterization were complex, and he wrote and spoke frequently about those ideas (I direct you, especially, to his essay “The Concept of Character in Fiction”), but I will try to communicate the essence of his thinking.

Drawing from the essay above: He wrote, “[T]here are some points in a narrative which remain relatively fixed; we may depart from them, but soon we return, as music returns to its theme. Characters are those primary substances to which everything else is attached . . . anything, indeed, which serves as a fixed point, like a stone in a stream or that soap in Bloom’s pocket, functions as a character” (49-50). As such, physical objects can be characters (everything from Lowry’s volcano to Gogol’s overcoat); symbols can be characters; ideas; concepts; situations. All can function a characters.

If we think of plot as what happens to a narrative’s central character (its protagonist), commonly how the character changes during the course of the narrative, we must be prepared to modify our sense of conflict, resolution and denouement when other things besides people operate as protagonists (and antagonists). A volcano or an overcoat or a crucifix or a bombing or fascism cannot have epiphanies (as Joyce would have phrased it). They do not change as, we hope, people change. No matter how many ghosts visit a volcano on Christmas Eve, it’s still a volcano on Christmas morning, with all the capricious and explosive qualities its kind is known to have.

To be clear, nearly all of Gass’s fiction is populated with human characters as their ostensible narrative focus (two exceptions are the brief stories “Don’t Even Try, Sam” and “Soliloquy for a Chair” in which the protagonist of the former is the legendary piano in the film Casablanca, while it is a folding chair in a barbershop that soliloquizes in the latter – both are collected in Eyes [2013]). However, the human characters’ primary function is to provide a scaffolding on which Gass can develop his thematic interests, and, perhaps chiefly, play with language. “For me,” he said, “a character is really a voice and a source of language. . . . Words are going to come out from that source either as direct speech or as a means of dictating the language you use in the third person to describe scenes or that individual from outside” (Saltzman 85). So, functionally speaking, human characters are providing the means (structurally and linguistically) by which Gass can explore other characters in the narrative: a concept, an attitude, a place, an object.

One may ask at this point: If in Gass’s fiction he was disinclined to maneuver his characters toward epiphanies, toward traditional, Aristotelean kinds of resolutions, how did he develop his narratives? What was their aim? In one sense, Gass developed a piece of fiction as one might develop an expository essay, with the objective being to more fully realize a particular subject. Ultimately, though, and overarchingly, Gass’s interest was to create a beautiful piece of writing: a work of art made of language. Perhaps he expressed his philosophy most clearly and most forcefully in a series of debates with fellow writer (and friend) John Gardner in the 1970s (audio recordings of one such debate session can be accessed here). Gardner believed that fiction should have a moral component, that it should teach the reader something important about how to behave in the world. Gass vehemently disagreed: “John wants a message, some kind of communication to the world. I want to plant some object in the world. . . . I want to add something to the world which the world can ponder the same way it ponders the world” (LeClair 48). Elsewhere Gass bluntly asserted that “literature in not a form of communication” (Duncan 49).

Since we are a gathering of writers, I want to end on what Gass believed to be a kind of side benefit of using artful language, a utilitarian additional advantage. He said, “Shakespeare succeed[s] mainly because the rhetoric succeeds. Psychological shifts, changes of heart, all sorts of things happen which are inexplicable, except that if the speech is good enough, it works. The same is true in the way I go at things” (Saltzman 83-4). To put it plainly, certain weaknesses in a narrative can be bolstered by using language beautifully. Readers can be distracted from fissures in the foundation if the architecture is elaborate and enchanting. May we all build such mesmerizing abodes with our material of choice: the English language.

Works Cited

Duncan, Jeffrey L. “A Conversation with Stanley Elkin and William H. Gass.” The Iowa Review, vol. 7, no. 1, 1976, pp. 48-77.

Gaddis, William. The Letters of William Gaddis, edited by Steven Moore, New York Review Books, 2023.

Gass, William H. Fiction and the Figures of Life. Knopf, 1970.

LeClair, Thomas. “William Gass and John Gardner: A Debate in Fiction.” Conversations with William H. Gass, edited by Theodore G. Ammon, UP of Mississippi, 2003, pp. 46-55.

Saltzman, Arthur M. “An Interview with William H. Gass.” Conversations with William H. Gass, edited by Theodore G. Ammon, UP of Mississippi, 2003, pp. 81-95.

—. “William H. Gass: Selected Correspondence.” Review of Contemporary Fiction,

vol. 11, no. 3, 1991, pp. 65-70.

—. “Language and Conscience: An Interview with William H. Gass.” Review of Contemporary Fiction, vol. 11, no. 3, 1991, pp. 15-28.

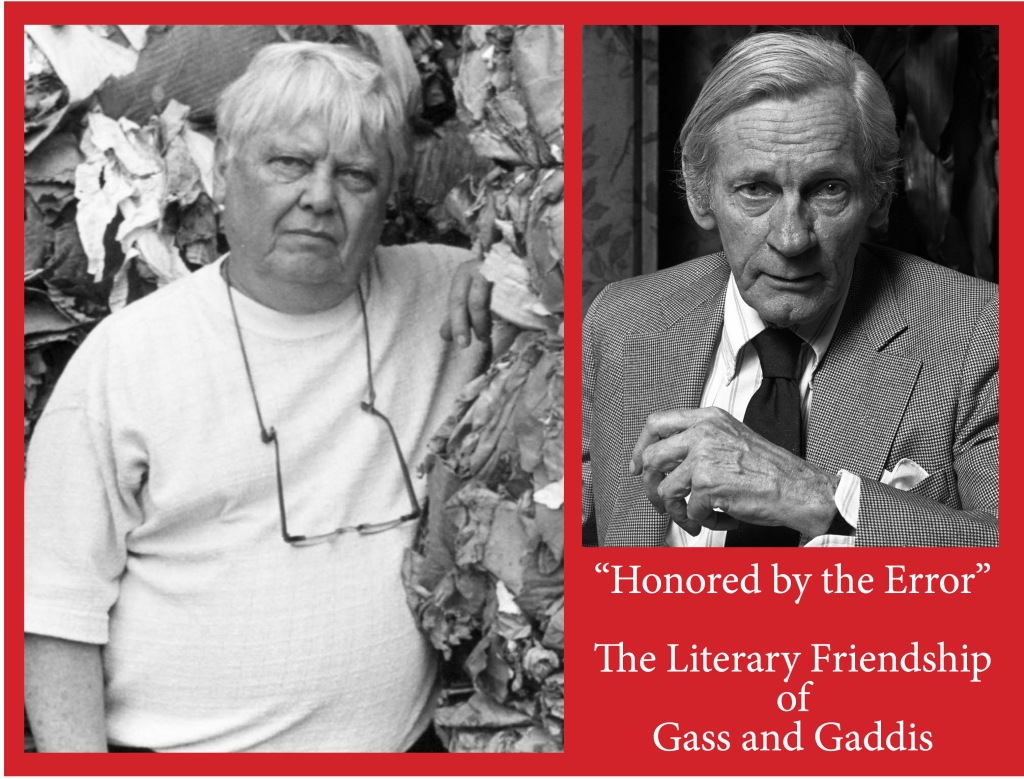

“Honored by the Error”: The Literary Friendship of Gass and Gaddis

The following paper was presented at the William Gaddis Centenary Conference, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri, October 20-22, 2022. It was part of the opening panel on Friday, Oct. 21, “Historical Gaddis & Literary Gaddis.” I had the honor of introducing the keynote speaker, Steven Moore. See the end of this post for my introductory remarks.

Anyone who knows William Gaddis or William Gass more than just a little likely knows of their long friendship. They first met at the National Book Award ceremony April 21, 1976—Gass being one of the judges that gave the prize to J R—and when Gaddis was near death in 1998 Bill Gass was one of the last people he wanted to speak to. Unfortunately Gass received the message too garbled and too late, and that final telephone conversation never took place. Throughout their more than twenty-year friendship, they supported each other’s work in myriad ways, both publicly and privately, and they shared in the amusement of people confusing them due to their sound-alike names and similar ambitions when it came to the written word.

I’m ashamed to admit that I was nearly 40 when I learned of both writers practically simultaneously, which I hope indicts the shortcomings of the U.S.’s literary culture more severely than it does my own. What I mean is, I read Gass’s brilliant introduction to The Recognitions before embarking on my maiden voyage into Gaddis’s now-mythical inaugural novel. Indeed, Gass’s introduction is probably almost as well known as the novel itself, and quite possibly more frequently read than the masterpiece it precedes in the Penguin Classics edition. The intro took on a life of its own, being reprinted in various iterations and quoted countless times. Unlike the book it introduces, the piece’s brilliance was recognized (sorry) from the start. Michael Millman, senior editor at Viking Penguin, wrote to Gass on January 21, 1993: “Would you have any objections to our approaching The New York Times Book Review [sic] about running your introduction? In my experience . . . I can’t remember another time when we had an essay of this caliber as an introduction to one of our volumes. . . .”

As we recall, Gass begins the piece by talking about the enigmas and confusions surrounding William Gaddis. Writes Gass, “Even The New York Times, at one low point, attributed his third novel, Carpenter’s Gothic, to that self-same and similarly sounding person. Yes, perhaps William Gaddis is not B. Traven after all, or J.D. Salinger, Ambrose Bierce, or Thomas Pynchon. Perhaps he is me” (179). What follows is where I borrowed for this paper’s title: “When I was congratulated,” continues Gass, “I was always gracious. When I was falsely credited, I was honored by the error.” In his tribute to Gaddis, in 1999, Gass said that he “could enjoy these mistakes, since Gaddis seemed equally amused” (204).

It’s difficult to say when the two writers became aware of each other’s work. They were close contemporaries. Gaddis was born in 1922, Gass in ’24. The Recognitions came out in 1955, the same decade that Gass’s earliest fiction began to appear (the literary journal Accent, published by University of Illinois-Urbana’s English Department, co-edited by Stanley Elkin, included three pieces by Gass in its Winter 1958 number). Gass’s writing began to appear here and there in this journal or that (unlikely to be on Gaddis’s radar), but his first novel, Omensetter’s Luck, came out in 1966, quickly followed by In the Heart of the Heart of the Country (a collection of novellas and stories) and Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife (a wildly experimental novella), both in 1968, and Fiction and the Figures of Life (a collection of essays, including essays on the writer’s craft), in 1970. The essays were well regarded by Gass’s peers. We know, for example, that Cormac McCarthy acquired a copy of the collection while he was writing Child of God, published in ’73 (King 31).

It seems fair to assert, then, that by the ’70s both Gaddis and Gass had read one another, and apparently approvingly. In a Gaddis letter dated March 17, 1976, having to do with J R’s National Book Award nomination, he references Gass, writing to his second wife Judith, “But if the book selections are odd, the judges are even odder; a writer, a critic, and a complete idiot: Wm Gass, Mary McCarthy, and Maurice Dolbier” (Letters 310). Compared to the epithet he uses for Dolbier, a novelist among other things, too, the neutrality of “a writer” almost sounds like praise. That same year, 1976, Gass talks about Gaddis in his “Art of Fiction” interview in The Paris Review, specifically in response to Thomas LeClair’s question “Who are some living novelists you respect?” Gaddis makes the list. Gass says he admires Gaddis for the same reasons he admires John Barth: “What I like . . . is the unifying squeeze which that great intellectual grasp of his gives to his work, and the combination of enormous knowledge with fine feeling and artistic pride and total control. I really admire a master” (37). Gass underscores Gaddis’s masterful control of the narrative apparatuses in his books.

Gass read his peers’ work and commented on it regularly, in interviews, guest lectures, critical articles, and book reviews. Gaddis, on the other hand, was not inclined to read his contemporaries. Steven Moore writes that “[h]e seemed to have little interest in the novels of those contemporaries with whom he is most often associated,” including Barth, Barthelme, Robert Coover, Don DeLillo, John Hawkes, Cormac McCarthy, and Thomas Pynchon. “William H. Gass was an exception,” says Moore, “whom he admired both personally and professionally” (William Gaddis 13). At the tribute to her father in 1999, Sarah Gaddis said, “William Gass was important to Gaddis. . . . He held Gass in the highest esteem for his work, and no other writer made him feel so understood” (150-151). This respect for Gass and his opinions, literary and otherwise, is made clear by Gaddis’s frequently quoting or paraphrasing his friend in letters to others over the years (e.g. see Letters pp. 423, 459, 464, 477 and 481); and his admiration for Gass’s abilities as a writer is put plainly in an April 13, 1994, letter to Michael Silverblatt, host of the literary radio program Bookworm: “Gass is for me our foremost writer, a magician with the language” (Letters 507).

Similarly, Gass’s admiration of Gaddis had a great deal to do with his poetic use of language. In a 1984 interview with Arthur M. Saltzman, Gass said that “all the really fine poets now are writing fiction. I would stack up paragraphs of Hawkes, Coover, Elkin, or Gaddis against the better poets writing now. Just from the power of the poetic impulse itself, the ‘poets’ wouldn’t have a chance” (91). In Gass’s introduction to The Recognitions he writes about the poetry of both that book and J R, saying: “. . . J R was as different from the earlier novel as Joyce from James. But do not put down what you have to go to J R yet, even if it is almost as musical as Finnegans Wake. . . . [W]e must always listen to the language; it is our first sign of the presence of a master’s hand; and when we do that, when we listen, it is because we have first pronounced the words and performed the text, so when we listen, we hear, hear ourselves singing the saying . . .” (184).

After their meeting at the National Book Award ceremony, the two writers became fast friends. The following year they were slated to be at a writers’ conference in Sarasota, Florida, and Gaddis’s participation was somewhat contingent on Gass’s being there, also. In a March 18 letter to Judith, Gaddis laments that other writers had canceled or declined—namely Barth, Susan Sontag, and Donald Barthelme—and says that “if Gass abruptly disappears I may be tempted to do the same.” Gaddis explains that he was looking forward to “hav[ing] a good & encouraging talk with William Gass [who is] coming with his wife [Mary].” Otherwise Gaddis had been “shying from readings and panels” because they interfered with his writing process. He notes that “Gass admires me because I’ve been able to stay out (till now), I admire him because he separates it all clearly & relaxedly in his head” (Letters 319). Later that year, Gaddis was scheduled to appear at an event closer to home, in Stonington, New York, for which—he says in a July 7, 1977, letter to Joy Williams and Rust Hills—he was “girding his loins.” Part of his trepidation was that “it won’t have Gass” (321).

Reading their personal correspondence, filled with warm regards and jokes that each man knows will land because of their kindred kinds of humor, it is obvious how much they genuinely liked each other. An excellent example of this tone appears in a letter to Gass dated August 25, 1980, in which Gaddis alludes to a previous trip to Washington University in St. Louis. Gaddis begins, “Dear Bill. Attending a stylish Hamptons opening of a very good painter [Polly Kraft] out here.” He believes that Gass will appreciate her art and has enclosed some slides of her paintings. He says, “I inveigled them from her on grounds of your sterling generous & rowdy character & Mary’s good looks.” Then, “I write this on the assumption that you are still alive, after day after day reports of 114° in St. Louis (my recollection being -10°)” (Letters 358). Gaddis had been in St. Louis in February 1979 for a three-week teaching session at Wash U. A few months beforehand (October 14, 1978) he wrote to his daughter Sarah about receiving “a letter from Washington Univ in St. Louis (where Bill Gass is)” with the teaching proposal. The letter was from Stanley Elkin, a writer who is “marvelous.” Gaddis says that he “accepted immediately . . . mostly for the prospect of rowdy time with Elkin & Gass & I’m really looking forward to it. I think we’ve all 3 got similar views on what good writing’s about plus highly compatible senses of humor” (Letters 341). He concludes the August 25, 1980, letter by encouraging Gass and his wife to visit him on Long Island when they can. It is an open invitation that Gaddis expresses in several letters.

Their relationship was not just about mutual admiration and sharing “rowdy” times together. They also did what they could to advance each other’s careers and reputations. Gass’s efforts on Gaddis’s behalf began with his judgment of J R for the National Book Award and continued for the next two decades. It included his writing the introduction for the Penguin edition of The Recognitions, and his being instrumental in bringing Gaddis to St. Louis to teach, and then again, in 1994, to contribute to a symposium on “The Writer and Religion.” What is more, Gass wrote a recommendation that contributed to Gaddis’s being awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1981. Gaddis wrote to him (April 12), “Do you KNOW what joy (read money, prestige, vainglory) your kind effort has contributed to this modest household?” (Letters 361). Gaddis, for his part, appeared to always have Gass’s best interests at heart. In the 1980 letter in which he references St. Louis’s harsh weather, he also writes that he “escaped Knopf for Viking (a move I’d encourage you in . . . enthusiastic leaves-you-alone . . .)”; and he recommends a specific editor at Viking he thinks Gass would like (Letters 358). In 1991 and ’92 Gass more or less sequestered himself at the Getty Center in Los Angeles, to complete, at long last, his novel The Tunnel, which he’d been writing since 1966. Gaddis wrote to him at his Santa Monica address to offer some comic relief (composing much of the letter in Huck Finn-esque dialect), as well as encouragement and support. He says, “[I]t would be something if we both finished these god dam books this same year 1992 . . .” (“Letter [January?] 1992”). Gaddis, presumably, is referring to A Frolic of His Own, published in 1994. Gaddis informs Gass that his daughter Sarah is soon to arrive in California also and closes by saying “let me know if theres [sic] anything I can do for you here.”

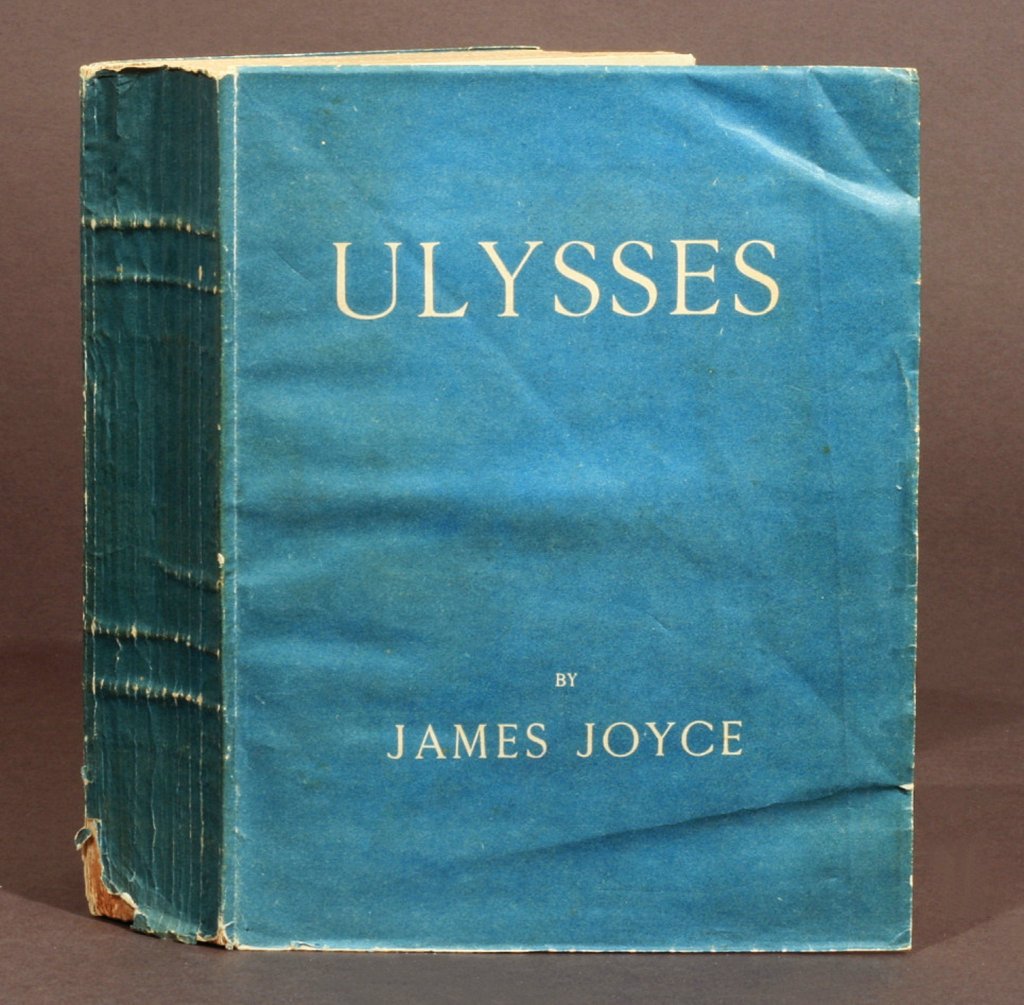

If one were to do a Venn diagram (so popular these days) of the two writers’ influences, there would of course be notable common ground. Both had a taste for some Medieval authors as well as Elizabethans, especially Donne and Shakespeare (Gaddis’s favorite play was As You Like It, while Gass counted Antony and Cleopatra as one of his “Fifty Literary Pillars” [Moore 11; Gass 36]). Contemporary European authors were among each man’s favorites, perhaps most notably Rilke, who was Gass’s literary lodestar. They had their differences too, however. Gaddis claimed to have read little of James Joyce, in spite of the critics who were convinced of the Irish writer’s influence; whereas Gass counted Ulysses and Finnegans Wake among his “pillars” and alluded to Joyce frequently in his nonfiction. Perhaps the most significant disagreement centered around Russian novelists, particularly Dostoevsky, whose place for Gaddis, says Steven Moore, was “paramount” (10).

This difference of opinion was comically and touchingly captured by Gass in his piece about the two writers’ participation in a trip to Soviet Russia in 1985, which included frigid visits to landmarks associated with Dostoevsky and especially his writing of Crime and Punishment. Gass was in the mood to be flippant and wanted Gaddis to be too. Writes Gass, “Gaddis’s love for the Russian novel—and for the predictable Russians at that—had surprised me, though in hindsight it shouldn’t have, if I’d kept The Recognitions fully in front of me . . .” (94). As such, Gaddis didn’t “relish [Gass’s] popping off” during the tour, and Gass’s wife Mary worked to keep his tongue in check by squeezing his arm when she knew he was about to say something that could prove regrettable. Gass continues, “I could see [Gaddis’s] youthful love glowing plainly when our group visited Dostoyevsky’s apartment. The sight of the master’s desk actually wet Willy’s eyes. I envied him. When my eyes moistened, it was only for Bette Davis, and such a shallow show of weakness made me angry with my soul” (196-97).

Gass concluded his tribute to his friend by recounting Gaddis’s arrival at a celebration in his honor in Cologne, Germany: “Gaddis slowly emerged into a starfall of flashbulbs worthy of the Academy Awards, the popping of a hundred corks” (205). I don’t believe in an afterlife, although I think it’s a swell idea. In fact, I like to imagine a Literary Great Beyond, a kind of Valhalla for writers instead of warriors. And if such a place did exist, I would hope that the great friends, Gaddis and Gass, were both greeted as novelist titans just as Gaddis was on that glorious Teutonic night.

Works Cited

Gaddis, Sarah. “A Note of Gratitude.” Conjunctions 33, 1999, pp. 149-51.

Gaddis, William. Letter to William H. Gass. [January?] 1992. Gass Papers, Washington University in St. Louis.

——. The Letters of William Gaddis, edited by Steven Moore, Dalkey Archive Press, 2013.

Gass, William H. A Temple of Texts. Dalkey Archive Press, 2007.

King, Daniel Robert. Cormac McCarthy’s Literary Evolution: Editors, Agents, and the Crafting of a Prolific American Author, The U of Tennessee P, 2016.

LeClair, Thomas. “William Gass: The Art of Fiction LXV.” Conversations with William H. Gass, edited by Theodore G. Ammon, UP of Mississippi, 2003, pp. 17-38.

Millman, Michael. Letter to William H. Gass. 21 Jan. 1993. Gass Papers, Washington University in St. Louis.

Moore, Steven. William Gaddis: Expanded Edition, Bloomsbury, 2015.

Saltzman, Arthur M. “An Interview with William Gass.” Conversations with William H. Gass, edited by Theodore G. Ammon, UP of Mississippi, 2003, pp. 81-95.

Keynote Introduction of Steven Moore

I don’t recall the context, but some twenty years ago I said “Everything I know about William Gaddis I learned from Steven Moore.” For the past few weeks, in anticipation of this conference, I’ve been getting back into a William Gaddis state of mind, and it occurred to me that the statement is still true. Everything I know about William Gaddis I learned from Steven Moore. Like so many of us, I first encountered Steven’s scholarship while grappling with The Recognitions. His Reader’s Guide, first published in 1982, was an invaluable lifeline. A revised edition appeared in 1995, and an edition translated into German was brought out in 1998. As my own interests were sparked by Gaddis’s work, Steven continued to be my guide, especially his critical biography of Gaddis and his books, simply titled William Gaddis—both the 1989 edition, and the expanded edition of 2015. As if being the founder and leading voice of William Gaddis studies wasn’t enough, Steven has produced scholarship in an impressively diverse range of areas; perhaps most notable are his two volumes of The Novel, An Alternative History, the latter of which won the Christian Gauss Award for literary criticism in 2013. However, one of the more obscure credits on his bibliography is the most personally meaningful to me. In 2012 I was finalizing my first academic book for publication—a postmodern take on the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf—and my publisher was hoping I could land a scholar of note to write the book’s foreword. I was hoping that too. A few years earlier I’d had one brief exchange of emails with Steven. He’d actually contacted me for assistance with a Gaddis project (I think he was editing the letters). In my recollection I was little to no help. However, that one exchange encouraged me to reach out to Steven about writing the foreword. To my surprise, he agreed to do it. I sent him the manuscript and in short order he’d written a wonderfully insightful, not to mention generous, opening for the monograph. My only concern was reading reviews that would say something like “What a terrific foreword—it’s too bad Steven Moore couldn’t have written the whole book.” Luckily for us all, Steven has written several whole books, and he’s not done yet. This coming spring, Zerogram Press will release his memoir Dalkey Days about his time with the legendary Dalkey Archive Press from 1987-96. We have to wait a bit for the book, but our time of waiting to hear this keynote address—on “New Directions for Gaddis Scholarship”—is over. Please help me welcome Steven Moore.

Joyce’s Ulysses as a Catalog of Narrative Techniques for MFA Candidates

(The following paper was presented at the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association Conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Feb. 26, 2022, moderated by Yasminda Choate, Seminole State College.)

I must say regarding the title of this talk: what it lacks in cleverness it at least makes up for in near-childlike self-explanation. I’m going to discuss why focusing an entire course on a single daunting text like Ulysses is worthwhile, at least in the setting of an MFA program; and I’m going to offer some specific suggestions for reading focuses and writing assignments. (It’s not one of those papers you run into at conferences sometimes, a paper that purports to be about how waxed fruit influenced the writing style of Gertrude Stein, and ten minutes in the presenter hasn’t yet mentioned waxed fruit, Gertrude Stein, or writing style, or, for that matter, writing.)

First some further context: I teach in an MFA in Writing program that has both on-campus and online courses of the two traditional varieties: workshop and literature. I teach online literature courses exclusively. Nevertheless, I do think this course, or this kind of course, could work just as well in-person. I have the luxury of designing my own courses. Maybe three years ago, I decided to pitch a course with a singular focus: James Joyce’s legendarily difficult novel Ulysses. My thinking was that it would be a great text for discussing a wide array of narrative techniques, all gathered together in one unruly place. Also, for people planning to be fiction writers (meaning probably novelists) and perhaps wanting to be college teachers themselves, being familiar with the book that many consider the greatest English-language novel of the twentieth century, if not of all time, would be beneficial—if for no other reason than to avoid embarrassment at some future department mixer.

I’ve now taught the course several times (four?), and it’s scheduled again for this summer. From my perspective it’s been a success, and also a blast to teach. Student evaluations support my perspective. (Pro tip: I call the course “Joyce’s Ulysses” to try to avoid confusion; nevertheless, I do get the occasional student hoping to take a deep dive into Homer—which would also be a great course.) The course attracts students with a variety of motives, but a common one is that they’ve tried reading Ulysses before—and have had to limp, defeated, from the field of battle (a nod to Ulysses’ first publishers, Jane Heap and Margaret Anderson). Or, often, it sat on a shelf, untouched, glaring arrogantly at its owner for years. Now, with some guidance and the motivation of a grade hanging in the balance, they hope to slay the beast, or at least land a scratch.

I can relate. I’m among those who tried and failed a few times to read Ulysses before finally getting through the text in its entirety. So as a recovering Ulysses failure, I can speak to the students on their own level of self-loathing, and offer them the sort of encouragement they need to not drop the course after seeing the reading requirements. When I started teaching Ulysses we had eleven-week sessions; then the program was revised to offer eight-week sessions. The book was a bear to teach in eleven weeks, so eight is extra challenging. Yet doable.

We look at two episodes per week, and tackle an inhumane amount of material the penultimate week, episodes 16, 17, and 18; that is, Part III, “Eumaeus,” “Ithaca,” and “Penelope,” some 150 pages—which isn’t unusual in a typical grad course, but it’s 150 pages of Ulysses, capped off by Molly Bloom’s nearly punctuation-free, stream-of-consciousness monologue. To accommodate the move from eleven weeks to eight weeks, I basically cut Part I, the three opening episodes that focus on Stephen Dedalus, and begin in earnest with Leopold Bloom starting his day in Episode 4, “Calypso.” I provide a summary of those opening episodes and encourage students to read them even though they aren’t required per se.

I stress—again and again—that our purpose is not to unlock all the literary mysteries of the novel. Joyce specialists (of which I am decidedly not one) devote whole careers to the book, or only individual episodes. Rather, we want to achieve a basic understanding of what happens in the book, yes, but more importantly we want to lift the hood and see what Joyce was up to in individual episodes, and in the structure of the novel as a whole. In other words, we’re reading the novel as practicing writers, not as literary scholars. I hope to spark an interest in Joyce so that later in life students may feel warm and fuzzy enough about Ulysses to return to it, and to engage with other Joyce texts. Typically I do have a few students who’ve been bitten by the Joyce bug by the end of the session, and they ask for recommendations about where to go next, unaided. Finnegans Wake?, they sometimes ask. God no. I generally recommend Dubliners, and even more specifically “The Dead,” which is available in stand-alone critical editions if a reader is so inclined.

Another piece of advice I offer at the outset: The novel features a cast of thousands, and trying to synthesize all of the characters into your gray matter for easy recall later is probably one of the reading habits that leads to so many normally successful readers giving up in a hailstorm of self-condemnation. Instead, I say, there are just three main characters—Stephen, Bloom, and Molly—so keep an eye out for them. As long as you have a sense of what they do in the novel, from episode to episode, until you reach the Promised Land of “Yes” at the end of 18, then you’re doing just fine.

(We do get into some literary analysis, and one of the aspects we talk about is the novel’s unusually encyclopedic nature, and that Joyce didn’t intend, probably, for it to be read like a typical novel. There’s just too much data to try to hold in one’s head from start to finish. I will admit that in spite of reading the novel from stem to stern at least twice, and some sections multiple times, and even having published about it, plus taught it multiple times, it’s not uncommon for me to read an article or hear a presentation on the novel, and think, “That happens in Ulysses? Really? That sounds interesting.”)

Students are required to write weekly discussion posts based on the episodes, and I give them something concrete to glom onto. I share with them the famous Ulysses schemas, the Gilbert and the Linati, and ask them to write about how two of the elements operate in the week’s readings. Again, I don’t pretend that this an approach that will help them penetrate to the core of the novel’s meaning. Rather, as writers we’re looking at ways that Joyce tried to unify eighteen episodes, or chapters, that use increasingly experimental techniques of storytelling and shift point of view frequently. The schemas are one method, as are the running parallels with Homer’s Odyssey (which are often hard to spot even when one knows to look for them). Another unifying element is Joyce’s attention to chronology, with the narrative unfolding in more or less accurate time over 24 hours. Finally, there is Joyce’s attention to the point of obsession regarding the geography of Dublin in June 1904.

The novel is famous for its stream-of-consciousness narration, which nowadays isn’t exactly revolutionary. Joyce is, however, a master of the technique so a closer examination of almost any episode can lead to a fruitful discussion of how it’s working in detail. “Penelope,” of course, is the example par excellence of interior monologue. To mimic the randomness of one’s thought process, Joyce uses almost no punctuation for more than 30 pages, a section broken into only eight “sentences.” Nevertheless, we can isolate specific thoughts and images. How does Joyce manage it, without the traditional use of punctuation?

Every episode offers a multitude of techniques that could be of value to fiction writers, but in the interest of time here are some approaches that stand out to me.

Episode 4, “Calypso.” The opening three episodes, focused on Stephen Dedalus, establish a realistic chronological approach in the novel, from the start of Stephen’s day at the Martello tower to his meeting with Mr. Deasy to his walk along the strand. Then, abruptly, in this fourth episode time is reset to around 8:00 as we’re introduced to Leopold Bloom. From then on time in the novel unfolds consistently. The lesson: Don’t be afraid to break your own rules.

Episode 6, “Hades.” Bloom takes a carriage ride with three men who are also attending Paddy Dignam’s funeral. Bloom is both part of the group and yet set apart from his companions because of his Jewish heritage and being seen as a quasi-foreigner. This feeling, of being alone in a crowd, is exquisitely human and has obviously been explored by writers and artists throughout history, but no one does it better than Joyce in this iconic episode. The lesson: How to create a character who is both accepted into a social circle while simultaneously being excluded from it.

Episode 7, “Aeolus.” Bloom visits the Freeman newspaper offices, where he has a series of encounters, including with Stephen for the first time in the novel. This episode initiates Joyce’s more overtly experimental techniques as he breaks up the narrative with frequent headline-like insertions throughout. These headlines were a relatively late addition to the episode as it was published without them in The Little Review. Lesson: Don’t be afraid to play with narrative techniques and step from behind the curtain as the storyteller.

Episode 9, “Scylla and Charybdis.” Here Stephen expounds on his theory regarding Shakespeare’s Hamlet in the National Library with a group of fellow literati. His theory has been alluded to previously in the novel. Intertextuality—bringing other texts to bear on the narrative’s primary text—happens frequently in Ulysses. Indeed, Homer’s Odyssey serving as a structural apparatus is itself intertextual. But the use of Hamlet as a well-known literary figure (perhaps the best-known literary figure) to amplify the novel’s own concerns about parent-child relationships, among other issues, is worthy of careful study. Lesson: Bring other texts into conversation with your own narrative.

Episode 10, “Wandering Rocks.” In this scene our attention wanders between a host of different characters and objects. Very little happens in terms of advancing the novel’s plot, but Joyce brings together many of the characters and items of significance we’ve already encountered. Many see this odd episode—with its cinematically sweeping point of view—as a way to tie the earlier (more conventional) chapters of the novel to the later (more experimental) chapters. Lesson: Chapters can have principal objectives other than to advance the plot or evolve characterization; they can serve more purely artistic functions.

Episode 12, “Cyclops.” We join Bloom in Barney Kiernan’s pub, but from the point of view of a new anonymous, first-person narrator. Besides the switch in POV, Joyce also plays with various prose styles, including Irish mythological, legalistic, journalistic, and biblical. This episode, then, breaks two cardinal rules young writers often learn in workshop: to be consistent when it comes to (1) point of view and (2) voice. Without warning, Joyce switches from third- to first-person, and then injects some thirty different prose styles into the telling. Lesson: Know the rules so that you can break them; or, the only rule when it comes to telling a compelling story is that there are no rules.

Episode 14, “Oxen of the Sun.” Joyce takes the technique of Episode 12—the use of multiple prose styles—and goes even further by emulating the evolution of the English language, from its Latin/Germanic roots to Anglo-Saxon to Chaucer to Shakespeare to Defoe to Lamb, and many more. The plot advances at the Holles Street maternity hospital, but it does so via this history of the stages of the English language. Lesson: Have fun. Don’t be afraid to toy with voices and styles within the same piece.

Episode 15, “Circe.” We find ourselves in Nighttown, Dublin’s red-light district, but now the storytelling mode is dramatic. The episode unfolds as a play script, complete with character names and stage directions. The lesson: Go ahead. Begin in one mode and switch to another; then back again, or whatever you feel like doing.

Episode 17, “Ithaca.” Bloom and Stephen walk to Bloom’s residence, an important plot advancement, especially in light of the novel’s Odyssey subtext, but now it’s told via a series questions and answers, resembling, most say, either catechism or Socratic dialogue. Lesson: Why the heck not?

And like Bloom, we return to Episode 18 and No. 7 Eccles Street.

A quick word or two on other kinds of writing assignments one might assign, besides the weekly posts tied to the schemas. For their final project, I have students try their hand at one or more experimental techniques they’ve encountered in the book, creating their own original scene. It’s a two-part assignment. There’s the creative writing itself; then there’s an analytical element in which they identify the episodes and techniques they used as inspiration, quoting and citing from the novel as needed.

In the original eleven-week version of the course, I attempted an ambitious midterm paper. I had students access an episode as it first appeared in either The Little Review or The Egoist (using the Modernist Journals Project online), and compare it to the 1922 book version, identifying Joyce’s revisions and speculating as to why Joyce may have made the changes (almost always additions) that he did. That is, what did he gain through revision? I think it’s a terrific assignment, but, as I say, ambitious, and students were not terribly successful with it. It is perhaps too labor intensive when up against the amount of reading students have to do just to keep pace with the syllabus. So when we went to eight-week sessions, I dropped the assignment. My main purpose was to emphasize the importance of revision and how much care Joyce took in revising his work. I think it’s a potentially fruitful exercise, and maybe given a longer time frame and the right students, it could be a reasonable assignment. (By the way, I did the activity myself, based on Episode 9, “Scylla and Charybdis,” and the brief article was published at Academia Letters—if you want to see an example of what I have in mind with the assignment.)

It’s especially interesting to be teaching Ulysses during its centenary year—an event that will add even more resources from which one might draw (not that there was a shortage previously). If you teach in the right circumstances, I encourage you to consider a course on Ulysses. Or if not that large, loose, baggy monster, maybe another long, challenging text. I’ve thought about War and Peace, but in eight weeks that would be quite a battle. I welcome suggestions.

Fictionalizing the Life and Voice of Washington Irving

The following paper — “Fictionalizing the Life and Voice of Washington Irving” — was presented at the North American Review Bicentennial Conference at the University of Northern Iowa, in Cedar Falls, which ran from June 11 to 13, 2015. This paper was part of the “Voice and Point of View” panel on June 13. Other papers presented were “Expanding the Powers of First-Person Narration” by Buzz Mauro and “The Art of Narrative Telling: Transforming Cheever’s Voice” by Grant Tracey. In addition to presenting, I also moderated the panel.

I’m here today to talk about writing my novel An Untimely Frost, which I worked on between about 2006 (I think) and 2011, eventually publishing it via my own press, Twelve Winters, in 2014—Twelve Winters Press, by the way, has a table at the conference. The inspiration for the novel was Washington Irving’s rumored courtship of Mary Shelley. It seemed to me that a romantic relationship between the author of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and the author of Frankenstein could make for an intriguing chemistry. I didn’t know where or when I’d learned of that rumor, and I wasn’t especially interested in verifying its accuracy because I decided very early on that I wasn’t going to write a fictionalized biography of Irving and Shelley and their time together. Rather, I was going to use them as sources of inspiration and an armory of period details as needed. [As noted, I didn’t research the actual relationship between Irving and Shelley when writing the novel; however, in preparing this talk I came across this rare book—The Romance of Mary W. Shelley, John Howard Payne and Washington Irving (1907)–which would be of interest to anyone who wanted to know more about the famous authors’ “romance.”]

For an earlier project, which resulted in the novella Weeping with an Ancient God, I wrote a fictionalized biography of author Herman Melville’s real-life experiences among cannibals in 1842. I was dedicated to staying true to the established details of Melville’s life and times, which made for a challenging artistic endeavor. I like to believe that the novella turned out pretty well, but oftentimes I did feel hemmed in by reality and by Melville’s biography. Not to mention, real life rarely provides us with a satisfying narrative arc, which tends to handicap a novelist. It’s a bit like running in a three-legged race. It’s an experience all its own, but there’s no helping that the entire time one is keenly aware of how much easier it would be to race the usual two-legged way.

Thus, when I began writing about Irving and Shelley, I had no intention of shackling my creativity to their real lives. I began by concocting fictional names for them, eventually ending up with “Jefferson Wheelwright” and “Margaret Haeley.” I also decided early on that Jefferson Wheelwright would be my first-person narrator. I obviously had some familiarity with Washington Irving—and I’d taught “Sleepy Hollow” a couple of times in a college course—but I didn’t feel that I knew him and, more importantly, his voice well enough to create my Jefferson Wheelwright persona. To prepare, I did read several biographical sketches of Irving and more of his fictional stories. However, what I really wanted to steep my brain in was his real-life speaking voice, and the closest I could come to that, given that he lived in the early and mid nineteenth century, was to study his published letters.

I got hold of two collections in particular, both edited by Stanley T. Williams. One collection, brought out by Harvard University Press, concerns Irving’s letters “from England and the Continent, 1821-1828,” and the other, brought out by Yale University Press, consists of his letters “from Sunnyside and Spain,” spanning the years 1840-1845. I made use of both collections, and in fact one of the epigraphs for the novel comes from a Madrid 1842 letter. However, I found the letters from the earlier period to be more helpful since they correspond more closely to the time frame and the geography of my novel’s setting.

I culled the letters, along with biographical information, for two sorts of material. First, while I wasn’t writing a fictionalized biography based on Irving’s life, I was open to transferring and transforming real-life details from Irving to my creation, Wheelwright. Second, and more vital, I wanted to capture as nearly as possible Irving’s narrative style.

Without reading through the biographical notes and letters in their entirety again, it’s difficult for me to recall all that I borrowed in terms of real-life details and events. I did skim through the letters in preparation for this presentation, and I was surprised in a couple of instances regarding details that in my recollection I had wholly made up, but in actuality stemmed from my research.

One of the character details that I know I extracted from Irving’s letters had to do with a skin condition of his legs and feet that plagued him in the 1821-28 period. For instance, he writes from Germany on August 20, 1822: “I grew very lame in trudging about the dutch [sic] towns, and unluckily applied a recipe given me by old Lady Liston (may god bless her, and preserve her from her own prescriptions!)—it played the vengeance with me [. . .] I could scarcely put my feet to the ground & bear my weight upon them [. . .]” (“Wi[e]sbaden” 19). Elsewhere Irving talks about seeking treatment from various physicians. I decided early on in the writing process that some sort of foot condition would be part of my Jefferson Wheelwright’s situation. I guess I vaguely thought it might have some metaphorical value, connecting to his fear that he was not evolving, not moving forward, as a writer and artist. In An Untimely Frost, Wheelwright requests the aid of a London physician, Dr. Carter. In Chapter 2, I write,

On the first morning, he listened to my complaint while touching and gently kneading my feet and toes, which were blotchy red, except around the toenails where the skin was a vibrant purple. Spots on my feet were pained to the touch while my toes were dead numb. [. . .] The good doctor said it was a circulation problem; he said that even though exercise irritated my feet, rest was counterproductive, that we must increase the blood flow to nourish the nerve fibers.” (11)

In reality, Irving was laid up for days and even weeks with bouts of his “cutaneous condition,” but I didn’t think that would make for an especially exciting narrative, to have Jefferson Wheelwright lying around his hotel room for days on end nursing his feet, so I had Dr. Carter prescribe exercise. Carter becomes an important character in the novel—although when I first introduced him in the second chapter I had no idea whether it would be a cameo appearance or lead to a larger role.

In addition to physical details I also borrowed one of Washington Irving’s personality traits, namely his lack of interest and acumen when it came to business affairs. He let his elder brothers manage the family’s business interests, while he focused on his literary aspirations. In my novel, I write:

So far I was having a splendid time lounging in the gigantic bed at The Saint Georges [hotel], drinking the black-black Italian coffee, and scribbling my tale. I even felt a brief—brief, mind you—pang of guilt at the idea that this is what I did to earn my keep in the world. Like many of the Wheelwright men, I’d tried my hand at business, but to dismal results. I simply do not have a head for numbers and inventories and so on—I can conjure whole worlds with my pen, yet adding a column of numbers and arriving at the correct result seemed beyond me (I believe because midway I would lose interest and begin daydreaming of haunted castles on lonely, wind-swept cliffs). (10)

There were numerous details from Irving’s life, especially his writing life, that I commandeered for my purposes, but even more important was capturing Irving’s narrative style—and in particular the style he used in his letters to friends and family, which was somewhat different, on the whole, than his published authorial voice, such as in The Sketch Book and Bracebridge Hall stories.

I wrote a brief essay about trying to capture Irving’s voice for Glimmer Train Press’s Writers Ask series (it appeared in number 54 and I reprinted it in An Untimely Frost). Since it is brief and to the point at hand, I would like to insert it here in its entirety:

Like the vast majority of writers who have come out of a university creative writing program, I was taught to write contemporary literary fiction. However, for over a decade now, I’ve been mainly attracted to historically based narrative, both as a reader and as a writer. When we think of writers tackling a story or novel set in another time and another place, we imagine them doing extensive research on things like people, on the chronology of events, on various aspects of the material world they are attempting to fabricate—and we tend to imagine rightly. For me, though, there is another sort of research that must go on as well, the results of which are not as easy to spot in a story as, say, an infamous assassination or an obsolete gadget; and that is researching the structure of language itself. It can be a nebulous term, but what I’m most interested in is a setting’s voice.

Voice should contribute to the ring of authenticity, to be sure, but, more than that, voice can actually compel the movement of the narrative; voice can shape its structure. William H. Gass spoke to this phenomenon in a 1976 interview for The Paris Review, saying that “word resemblance leads you on [as a writer], not form. So you’ve really got a musical problem, certain paragraphs you are arranging, and you imagine you are orchestrating the flow of feelings from one thing to another.” Gass summed up by saying, “Once you get your key signature, the theme inherent in the notes begins to emerge: the relationship between art and life and all that.” Gass, author of some of the most admired books in the English language, suggests that the physical structure of the words on the page—and the meanings, feelings, moods that they convey—help guide the writer to, essentially, everything else in the narrative: plot development, characterization, theme, setting. . . .

The importance of this sort of research in historically based fiction is nicely illustrated in Charles Frazier’s highly acclaimed novel Cold Mountain, which is set in Civil War-era Appalachia. In an interview available online, Frazier said, “I wanted the language of the book to create a sense of otherness, of another world, one that the reader doesn’t entirely know.” Frazier did library research regarding the material world he was creating, finding “words for tools and processes and kitchen implements that are almost lost words.” Beyond that, however, he was interested in “getting a sense of the particular use of language in that region, the rhythm of it.” Frazier culled period letters and diaries for much of his information, but he also had the benefit of having actually heard “that authentic Appalachian accent” when he was a child.

For my own writing I’ve been attracted to more distant times and places, and as such have not had the benefit of hearing period speakers so printed examples of voice have been my guideposts. Nevertheless, the feel and rhythm of the language can filter into one’s writing by paying attention to the linguistic structures. For my current project I’ve been creating a first-person narrator based on the American author Washington Irving. It isn’t a fictionalized biography. It’s more that Irving’s persona has been the primary inspiration for my protagonist. When I first became interested in the project, I tracked down an obscure collection of Irving’s letters that he wrote between 1821 and 1828. The book has been invaluable to me in my effort to develop an effective narrative voice.

Simply put, in Irving’s day a well-read New Englander structured the language in ways that sound quite foreign—quite exotic even—to us now. Take, for example, this letter written at “Beycheville,” France, October 17, 1825:

I have had something of a dull bilious affection of the system which has clung to me for more than two weeks past. . . . The greater part of Mrs Guestiers household, who have lately removed here, are unwell—I have tried to shake off my own morbid fit by exercise—I have been out repeatedly hunting, as there were two packs of hounds in the neighborhood, but though I have taken violent exercise I do not feel yet reinstated by it. (50)

The terms are spectacular, yes—heaven help anyone who contracts “a dull bilious affection” and Irving’s reference to “violent exercise” makes me think of junior high P.E. class—but even more meaningful to my eye and ear are the syntactic rhythms. Today one might say, “I’ve been feeling sick for a couple of weeks,” but for Irving the “affection of the system” has “clung” to him “for more than two weeks past.” The structure implies that his sense of unwell-being is a sort pernicious companion of whom he can’t quite rid himself, in spite of his taking “violent exercise”—giving the act of exercise a physicality, as if it were an item from the apothecary’s pantry.

Yet I have no particular interest in my protagonist’s contracting a bilious affection or partaking of violent exercise. Rather I want the structure of the language. I want to tell my own tale, but I want to form the sentences as Irving might have had he written of the same events nearly two centuries ago. I normally keep the book of Irving’s letters on my nightstand, and every so often I open to a random page and read awhile, perhaps a few pages but often as little as a sentence or two, because I’m not searching for information: I want to keep retracing the sentence rhythms in my brain, like wagon wheels along a worn track, so that when I sit down to write, the words flow as naturally in the direction of his prose style as if he (or someone like him) were composing them himself. (I must go now—I feel the onset of a bilious affection.)

There haven’t been a lot of reivews of the novel, and the ones that have appeared are somewhat mixed—but the reviewers seem to appreciate the narrative voice that I was able to create. For example, Anne Drolet writes in the North American Review: “Morrissey styles Wheelwright’s voice after the patterns and idioms of 19th-century British speech, and that choice lulls the reader into the historical setting” (47). I presume being lulled into a setting is better than being jarred into one. Cécile Sune says in her blog Book Obsessed: “The writing is beautiful and elaborate, and is a testament to the research Ted Morrissey conducted for this book . . . As a result, it feels like a Victorian novel”—ultimately, though, she only gave it three out of five stars on Amazon (damn it). And most recently William Wright writes for the Chicago Book Review: “There are moments of true brilliance in An Untimely Frost. It reads like it was written by a post-modernist emulating Henry James [I like that line], which proves to be an intriguing combination”—but Wright concludes with “Perhaps with more ruthless editing, the novel could have been a triumph. As it stands, it was a wonderful idea that wasn’t quite pulled off.”

I’ll tell you what, critics are hard to please.

My five years floating around in the fictional consciousness of Washington Irving was an interesting artistic experiment, and it really stretched me as a writer. When I finished with the novel, I began writing a series of interconnected short stories—each in third-person, with shifting points of view, and set for the most part in an unnamed Midwestern village in the 1950s. I finished the twelfth and final story just a few weeks ago, and eventually I’ll be bringing them out in a collection titled Crowsong for the Stricken. I’m considering other long-term writing projects at the moment, and one idea is to return to nineteenth-century London, but not Jefferson Wheelwright. Never say never, but I believe I’ve said all I care to say in the voice and persona of Mr. Wheelwright.

Works Cited

Drolet, Anne. Rev. of An Untimely Frost, by Ted Morrissey. North American Review Fall 2014 (299.4): 47. Print.

“An Interview with Charles Frazier.” BookBrowse [c. 1997]. Web. 9 June 2015.

Morrissey, Ted. An Untimely Frost. Sherman, Ill.: Twelve Winters Press, 2014. Print.

—-. “Researching the Rhythms of Voice.” Writers Ask #54. Portland, Ore.: Glimmer Train Press. Print.

Sune, Cécile. Rev. of An Untimely Frost, by Ted Morrissey. Book Obsessed 10 Oct. 2014. Web.

Williams, Stanley T., ed. Letters from Sunnyside and Spain by Washington Irving. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1928. Print.

—-. Washington Irving and the Storrows: Letters from England and the Continent, 1821-1828. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1933. Print.

Wright, William. “A Hot and Cold ‘Frost.’” Rev. of An Untimely Frost, by Ted Morrissey. Chicago Book Review 18 May 2015. Web.

(Note that the portrait of Washington Irving was obtained via Wikipedia at this link.)

1 comment