In the Heart of the Heart of William Gass Country

For me 2024 marks a special year: the centenary of William H. Gass (1924-2017). As a Gass scholar and devotee (disciple isn’t too strong of a word), I have various projects in the works to mark the Master’s 100th year — all part of my “preaching the Gass-pel,” an evangelism I embarked on more than a decade ago. No doubt I will use this forum to talk about some of those Gass Centenary projects, which tend to be formal and scholarly. It occurred to me that I also wanted to do something less formal, and more personal. It is not an overstatement to say that William H. Gass changed my life. His writing, his theories, his example as torchbearer in the cause of literature: everything has impacted me in ways that I can name and, doubtless, in ways that I cannot.

Thus, “William H. Gass at 100: A Reading Journal.”

My intention is that throughout 2024 I will post to my blog impressions and musings regarding Gass’s works and words: his fiction, his essays, his reviews, his translations, his thankfully copious interviews. I probably won’t post as frequently as I would like (for one thing, those other Gass Centenary projects are going to be time-consuming and labor-intensive), but hopefully I will be able to share some of the wisdom and insights that have been so meaningful to me, and in the process reflect on how they have affected me: my writing certainly, my teaching definitely, and, most profoundly so therefore also most elusively, my thinking.

I don’t have a set agenda for these posts. The various foci will be organically chosen. Nevertheless, there are some topics that I feel deserve particular attention: Gass’s philosophy when it comes to composing narratives; his magnum opus The Tunnel, which took him more than a quarter century to write; the influence of the German poet Rilke on Gass’s work; his innovative prose techniques; his unflagging support of other writers; and the late work, which hasn’t received nearly the attention it deserves.

That’s a lot, and I will almost certainly fall short of my ambitions. If this reading journal has any success it will be measured in the number of readers who, because of it, have their curiosity piqued and as such will read the Master, perhaps for the first time.

For this journal, I will begin where William Gass began for me, with my almost accidental reading of his long story (some say novella) “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country.” I have told the tale elsewhere. The year was 2009, and I was in the process of amassing as many books as I could afford having to do with postmodernism. I was in the final stages of a Ph.D. in English studies at Illinois State University, rather late in life (46 at the time). Over the previous seven years, chipping away as a part-time student, I had completed my coursework, passed the comprehensive exams, and had my dissertation topic approved. I was looking at the psychological origins of postmodernism, and my plan all along had been to focus on the work of Thomas Pynchon and, especially, William Gaddis.

One of the many books I’d purchased was a (very) used copy of Norton’s Postmodern American Fiction. The well-worn book had recently arrived, and one afternoon, after a day of teaching high school, I decided to thumb through it, briefly. One piece in particular arrested my attention because it was heavily highlighted in yellow by a previous owner of the anthology. Upon further inspection, I saw that it had a strangely long and redundant title, and it was broken up into small sections, each with its own heading.

I began reading the opening, subtitled “A Place,” which starts more in the shape of a poem than a short story: “So I have sailed the seas and come . . . / to B . . . / a small town fastened to a field in Indiana.” I was instantly ensorcelled by the writer’s prose, and I think it was this early set of sentences that hooked me, and hooked me for life: “It’s true there are moments — foolish moments — ecstasy on a tree stump — when I’m all but gone, scattered I like to think like seed, for I’m the sort now in the fool’s position of having love left over which I’d like to lose; what good is it now to me, candy ungiven after Halloween?”

I quickly discerned that “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” didn’t have a plot per se, at least not in a traditional sense, and it barely had a central character. If it did, it was an aging poet who has come alone to this small Midwestern town, a place that is described in poetic bursts: “Where sparrows sit like fists. Doves fly the steeple. In mist the wires change perspective, rise and twist. If they led to you, I would know what they were. Thoughts passing often, like the starlings who flock these fields at evening to sleep in the fields beyond . . .”

Like so many readers, I knew this place. I’d grown up in the Midwest, and when I encountered “In the Heart” I’d been teaching in a tiny town that reminded me in so many (unpleasant) ways of the fictional “B.” Moreover, I knew these feelings, especially of “having love left over.” I’d been surviving a miserable marriage for two decades, and the plan was to divorce as soon as I completed my doctorate (an agreement we’d reached to put off the inevitable).

As I said, my intention that fateful day was to only skim through the book to get a sense of its contents and what may be of use (I probably mainly bought the book for its introduction). But I couldn’t stop reading “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country.” In Gass I detected a kindred soul, and it was dawning on me that perhaps he would be a better focus for my dissertation than Pynchon and Gaddis. As good fortune would have it, within a week or two I attended the AWP Conference in Chicago. When I arrived at the hotel, late one frigid February night, I perused the conference program and discovered there would be a special program in honor of William H. Gass, a tribute, at which he would give a reading. What luck!

Again, this was 2009. Yet I recall the event and his reading with amazing vividness. It was in a ballroom that seemed suited for a thousand revelers, enormous chandeliers illuminated the room like a rugby pitch, revealing what appeared to be only a handful of audience members. I (im)patiently waited for three speakers to proclaim Gass’s greatness in frustrating detail. Finally the Master was allowed to speak. He had opted for an entomologically themed reading, beginning with his classic short story “Order of Insects,” followed by excerpts from other works that involve insects. I wasn’t yet familiar with Gass’s oeuvre, so I didn’t securely connect the passages to their works, but I know he read the swarm-of-grasshoppers scene from The Tunnel. Always self-deprecating, Gass joked that his reading demonstrated how little he had evolved as a writer over the decades.

Whatever had begun in me with the reading of “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” it was amplified, intensified and made permanent by the Master’s serendipitous reading at the AWP Conference. I went about collecting all of his works of fiction (at the time), as well as some of the nonfiction; and I changed my dissertation’s focus to Gass. Fortunately my dissertation director, Bob McLaughlin, was quite familiar with Gass, which proved a great asset as I retooled my approach.

Thus began my mission to spread the word about our greatest writer, William H. Gass. My evangelism has mainly taken the form of conference papers (with the majority of them delivered at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture Since 1900); but I have preached the Gass-pel elsewhere, including in Portugal and (in 2023) Singapore. Plus at the peak of the pandemic I organized an online symposium focused on The Tunnel, which turned 25 in 2020. For 2024, I plan to edit and publish William H. Gass at 100: Essays (currently just a Call for Papers).

I feel like I should say so much more about “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country.” Perhaps, instead, I will direct the curious to papers I’ve presented previously: “In the Heart of the Heart of the Cold War” (Louisville Conference, 2013); “In the Heart of the Heart of Despair” (American Literature Association Conference, Boston, 2017); and “From Tender Buttons to the ‘Heart of the Country'” (Louisville Conference, 2019). Note that this last paper includes images of early drafts of “In the Heart” from the Gass Papers at Washington University in St. Louis.

I’ll conclude by referring to the title of this post, “In the Heart of the Heart of William Gass Country.” What I mean by it, at least, is that Gass was known as a Midwestern writer. He was born in Fargo, North Dakota, but his parents soon moved to Warren, Ohio, where he graduated from high school in 1942. His undergraduate degree was from Kenyon College. His teaching posts were the College of Wooster (in Ohio), Purdue University, University of Illinois (Urbana), and Washington University in St. Louis. The settings of his stories, novellas and novels were consistently in the Midwest, sometimes explicitly, sometimes implicitly.

Though it likely proved a barrier to his work being embraced by the New York literary establishment, Gass had a great appreciation for the Midwest and how it could function in his fiction. He said in 1997, “The landscape that I work with — the weather and the geography — are designed to be projections of the interior state of the individual or the meaning of the scene. The actual Midwest landscape is by turns cold and beautiful, and like fall here now . . . the leaves are just drifting down, and it’s 72 degrees and gorgeous.” Then he added, “But, of course, you know it may rain in the heart if it rains in the town. That’s the idea. So if my scenery is bleak, it’s because the meaning or the characters’ souls are. It doesn’t mean the Midwest is.”

Thank you for reading my first William Gass reading journal. If I’ve whetted your appetite, “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” is available in both the collection In the Heart of the Heart of the Country and Other Stories (1968) and The William H. Gass Reader (2018). Or, like me, the ambitious could track down a copy of New American Review No. 1, where the story first appeared in 1967.

Here’s a video I made in conjunction with this blog post:

Beauty Must Come First: The Short Story as Art Made of Language

[This paper was presented at the 16th International Conference on the Short Story in English, held June 20-24, Singapore. It was part of the panel “The Short Story and the Aesthetics of Narration.” Other papers were “A Lot Like Joy: Fractured fragments represented within a composite narrative” by Sarah Giles, and “‘Writing back’—The Sideways Progress of Ideasthetic Imagining” by Julia Prendergast.]

“A second rate writer has no reason to exist unless he is on his way to being a first rate writer, and there is no point at all in doing pleasant easy things, or altering one’s conception of how a story ought to be to get it into print” (Saltzman, “Selected Correspondence” 66).

William H. Gass wrote this statement in a letter, in 1958, to an editor who was considering publishing his fiction, which would have been its first appearance in print. The editor was balking at Gass’s elaborate prose style. Gass, age 34 at the time, preferred to remain unpublished than have his words changed. It was an attitude he maintained – that to be edited was to be rejected – throughout what became a long and illustrious career that claimed numerous awards and distinctions, including Pushcart Prizes, Best American Stories, an O. Henry, the PEN/Nabokov Award, the American Book Award, and the William Dean Howells Medal. Gass – novelist, novella-ist, story-writer, critic, translator, and teacher – passed away in 2017 at the age of 93, working on his final project until he no longer had the energy to continue.

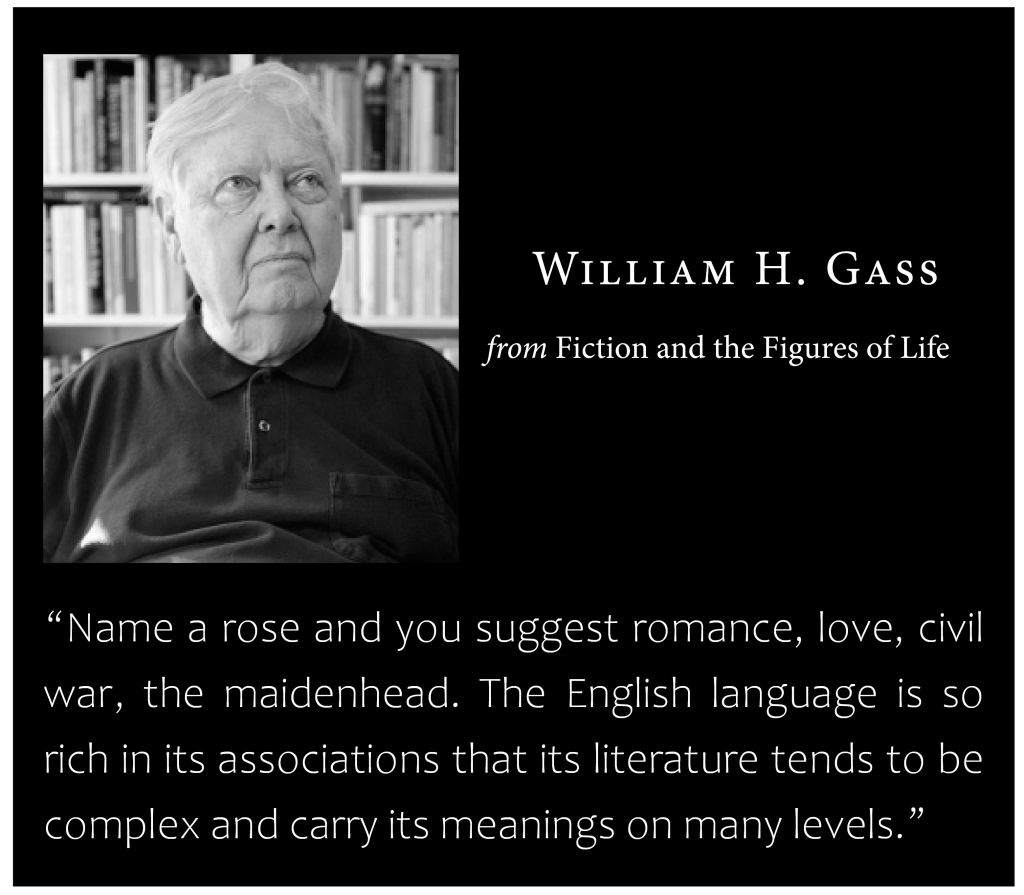

This paper is about Gass’s aesthetic theories when it came to producing narrative, and specifically fiction. Luckily, Gass was a generous granter of interviews, so we have a substantial amount of material in which he discusses his ideas about plot, character, setting, theme, symbolism … all of the elements we associate with storytelling (we have printed material, plus video and audio recordings that are available online). He also wrote numerous “craft” essays in which he goes into detail about his writing, as well as the writing techniques of others (among them Henry James, James Joyce, and Gertrude Stein). Such essays were included in his nine nonfiction collections, beginning with Fiction and the Figures of Life (1970) and concluding, for now, with Life Sentences (2012). And we have copious letters, which are carefully archived at Washington University in St. Louis.

To be clear, Gass’s theories are not designed to make one popular, that is, to make one a bestselling author. On the contrary, Gass never achieved that brand of success. In fact, he said (in another letter to the same editor, Charles Shattuck): “[S]uccess is merely failure at another level” (Saltzman 65), by which he meant that a writer must compromise their artistic principles in order to gain the public attention and financial rewards we (in the United States at least) usually associate with literary success. Gass’s primary goal was to create a work of literary art that he himself was satisfied with; if he had secondary goals they were to earn the respect of writers he admired, and to be read beyond his own lifetime. “I don’t write for a public,” Gass said. “[. . .] It’s the good book that all of us are after. I’ve been fortunate in that I think I have the respect of the writers whom I admire” (Saltzman, “Language and Conscience” 24). He did indeed as his work was praised by authors such as John Barth, Susan Sontag, John Gardner, Stanley Elkin, Joy Williams, and William Gaddis, who called Gass “our foremost writer, a magician with language” (Gaddis 629).

Regarding the goal of having his work read beyond his lifetime, it’s been my mission to make that a reality for more than a decade, during which time I’ve been “preaching the Gass-pel” (an expression coined by one of my students that I immediately filched). I’ve presented dozens of conference paper (all available at my blog, and some elsewhere); I’ve included readings of Gass’s work in my book Trauma Theory as an Approach to Analyzing Literary Texts (2021 edition); and I organized the website thetunnelat25.com, an online symposium devoted to Gass’s magnum opus. In my teaching I regularly place Gass’s books on my syllabi, and I share pearls of his writing wisdom with my students regularly (they may say obsessively). Many of these pearls I also share via social media in the form of memes that I’ve created. Like this one:

[This meme has to do with a topic I’ve recently written about: “To Plan or Not to Plan,” available here.]

And this:

[During the presentation I talked briefly about the inherent problem of writing workshops or writing groups: No matter how well-intentioned, peers’ critiques are oftentimes wrongheaded, and an offhanded criticism can send the unwary writer down a frustrating and fruitless rabbit hole. Instead, writers must accept the unavoidable subjectivity of reader response and stay true to their artistic vision.]

And this:

[I felt this was an especially apropos sentiment to share since the conference was comprised of writers from across the globe — but mainly Asia, Australia and Europe — who compose in English, even though for many it’s not their first language.]

I want to touch on some specific ideas Gass had about writing narrative, but before we get there I’m inclined to discuss the cornerstone of his aesthetic philosophy – as well as my primary focus here: Throughout his long writing career, Gass’s main interest was language, and he sought to use it as a painter uses paint, a sculptor uses marble or metal, a composer uses musical notes, or a photographer uses light and shadow. He stated, in a 1976 interview, “As a writer I only have one responsibility, and that’s to the language I’m using and to the thing I’m trying to make” (Duncan 53). He elaborated elsewhere, “Old romantic that I am, I would like to add objects to the world worthy of love. . . . My particular aim is that it be loved because it is so beautiful in itself, something that exists simply to be experienced. So the beauty has to come first” (LeClair 48).

Allow me to restate Gass’s central tenet: The beauty of the language must come first. By extension, then, everything else – all the other elements associated with fictional narrative, plot, characterization, setting, etc. – are subordinate to the quality of the language, to the beauty of the language. Gass’s devotion to beautiful language took many forms. For example, he regularly employed literary devices we normally associate with poetry: alliteration, assonance, rhyming, repetition. As such, Gass considered himself a stylist, meaning that his main interest was the writing itself. “I’ve always been interested in writing as writing. My interest in the various forms is dominated by an interest in style as such” (Duncan 64). Though Gass considered himself an abysmal poet, his use of poetic language was, he said, “compulsive” and “turns up in almost every line of prose, in sound patterns that get pushy, even domineering” (“Retrospection” 43-44).

Gass’s drive to create art made of language led him away from using narrative elements in traditional ways. Mind you, not ways that are utterly unique – I’m a supporter of Adorno’s assertion that when it comes to art, there is nothing new under the sun, yet the true artist must strive for the new nevertheless – but ways that are certainly unusual in modern American fiction, especially popular fiction. For instance, we normally think of characters in fiction as people, or possibly animals or machines (generally, though, personified animals or machines). However, for Gass a character was “any linguistic location of a book toward which a great part of the rest of the text stands as a modifier” (LeClair 53). Gass’s ideas about characters and characterization were complex, and he wrote and spoke frequently about those ideas (I direct you, especially, to his essay “The Concept of Character in Fiction”), but I will try to communicate the essence of his thinking.

Drawing from the essay above: He wrote, “[T]here are some points in a narrative which remain relatively fixed; we may depart from them, but soon we return, as music returns to its theme. Characters are those primary substances to which everything else is attached . . . anything, indeed, which serves as a fixed point, like a stone in a stream or that soap in Bloom’s pocket, functions as a character” (49-50). As such, physical objects can be characters (everything from Lowry’s volcano to Gogol’s overcoat); symbols can be characters; ideas; concepts; situations. All can function a characters.

If we think of plot as what happens to a narrative’s central character (its protagonist), commonly how the character changes during the course of the narrative, we must be prepared to modify our sense of conflict, resolution and denouement when other things besides people operate as protagonists (and antagonists). A volcano or an overcoat or a crucifix or a bombing or fascism cannot have epiphanies (as Joyce would have phrased it). They do not change as, we hope, people change. No matter how many ghosts visit a volcano on Christmas Eve, it’s still a volcano on Christmas morning, with all the capricious and explosive qualities its kind is known to have.

To be clear, nearly all of Gass’s fiction is populated with human characters as their ostensible narrative focus (two exceptions are the brief stories “Don’t Even Try, Sam” and “Soliloquy for a Chair” in which the protagonist of the former is the legendary piano in the film Casablanca, while it is a folding chair in a barbershop that soliloquizes in the latter – both are collected in Eyes [2013]). However, the human characters’ primary function is to provide a scaffolding on which Gass can develop his thematic interests, and, perhaps chiefly, play with language. “For me,” he said, “a character is really a voice and a source of language. . . . Words are going to come out from that source either as direct speech or as a means of dictating the language you use in the third person to describe scenes or that individual from outside” (Saltzman 85). So, functionally speaking, human characters are providing the means (structurally and linguistically) by which Gass can explore other characters in the narrative: a concept, an attitude, a place, an object.

One may ask at this point: If in Gass’s fiction he was disinclined to maneuver his characters toward epiphanies, toward traditional, Aristotelean kinds of resolutions, how did he develop his narratives? What was their aim? In one sense, Gass developed a piece of fiction as one might develop an expository essay, with the objective being to more fully realize a particular subject. Ultimately, though, and overarchingly, Gass’s interest was to create a beautiful piece of writing: a work of art made of language. Perhaps he expressed his philosophy most clearly and most forcefully in a series of debates with fellow writer (and friend) John Gardner in the 1970s (audio recordings of one such debate session can be accessed here). Gardner believed that fiction should have a moral component, that it should teach the reader something important about how to behave in the world. Gass vehemently disagreed: “John wants a message, some kind of communication to the world. I want to plant some object in the world. . . . I want to add something to the world which the world can ponder the same way it ponders the world” (LeClair 48). Elsewhere Gass bluntly asserted that “literature in not a form of communication” (Duncan 49).

Since we are a gathering of writers, I want to end on what Gass believed to be a kind of side benefit of using artful language, a utilitarian additional advantage. He said, “Shakespeare succeed[s] mainly because the rhetoric succeeds. Psychological shifts, changes of heart, all sorts of things happen which are inexplicable, except that if the speech is good enough, it works. The same is true in the way I go at things” (Saltzman 83-4). To put it plainly, certain weaknesses in a narrative can be bolstered by using language beautifully. Readers can be distracted from fissures in the foundation if the architecture is elaborate and enchanting. May we all build such mesmerizing abodes with our material of choice: the English language.

Works Cited

Duncan, Jeffrey L. “A Conversation with Stanley Elkin and William H. Gass.” The Iowa Review, vol. 7, no. 1, 1976, pp. 48-77.

Gaddis, William. The Letters of William Gaddis, edited by Steven Moore, New York Review Books, 2023.

Gass, William H. Fiction and the Figures of Life. Knopf, 1970.

LeClair, Thomas. “William Gass and John Gardner: A Debate in Fiction.” Conversations with William H. Gass, edited by Theodore G. Ammon, UP of Mississippi, 2003, pp. 46-55.

Saltzman, Arthur M. “An Interview with William H. Gass.” Conversations with William H. Gass, edited by Theodore G. Ammon, UP of Mississippi, 2003, pp. 81-95.

—. “William H. Gass: Selected Correspondence.” Review of Contemporary Fiction,

vol. 11, no. 3, 1991, pp. 65-70.

—. “Language and Conscience: An Interview with William H. Gass.” Review of Contemporary Fiction, vol. 11, no. 3, 1991, pp. 15-28.

Joyce’s Ulysses as a Catalog of Narrative Techniques for MFA Candidates

(The following paper was presented at the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association Conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Feb. 26, 2022, moderated by Yasminda Choate, Seminole State College.)

I must say regarding the title of this talk: what it lacks in cleverness it at least makes up for in near-childlike self-explanation. I’m going to discuss why focusing an entire course on a single daunting text like Ulysses is worthwhile, at least in the setting of an MFA program; and I’m going to offer some specific suggestions for reading focuses and writing assignments. (It’s not one of those papers you run into at conferences sometimes, a paper that purports to be about how waxed fruit influenced the writing style of Gertrude Stein, and ten minutes in the presenter hasn’t yet mentioned waxed fruit, Gertrude Stein, or writing style, or, for that matter, writing.)

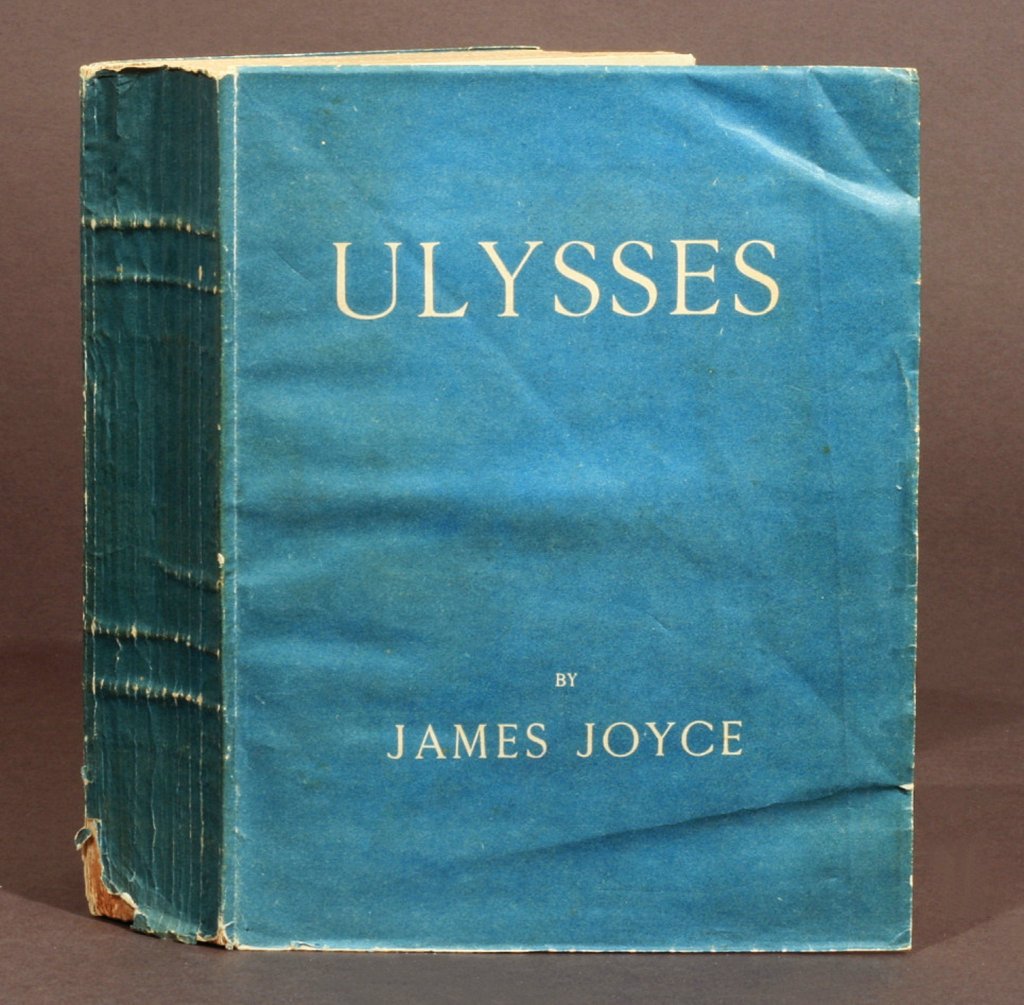

First some further context: I teach in an MFA in Writing program that has both on-campus and online courses of the two traditional varieties: workshop and literature. I teach online literature courses exclusively. Nevertheless, I do think this course, or this kind of course, could work just as well in-person. I have the luxury of designing my own courses. Maybe three years ago, I decided to pitch a course with a singular focus: James Joyce’s legendarily difficult novel Ulysses. My thinking was that it would be a great text for discussing a wide array of narrative techniques, all gathered together in one unruly place. Also, for people planning to be fiction writers (meaning probably novelists) and perhaps wanting to be college teachers themselves, being familiar with the book that many consider the greatest English-language novel of the twentieth century, if not of all time, would be beneficial—if for no other reason than to avoid embarrassment at some future department mixer.

I’ve now taught the course several times (four?), and it’s scheduled again for this summer. From my perspective it’s been a success, and also a blast to teach. Student evaluations support my perspective. (Pro tip: I call the course “Joyce’s Ulysses” to try to avoid confusion; nevertheless, I do get the occasional student hoping to take a deep dive into Homer—which would also be a great course.) The course attracts students with a variety of motives, but a common one is that they’ve tried reading Ulysses before—and have had to limp, defeated, from the field of battle (a nod to Ulysses’ first publishers, Jane Heap and Margaret Anderson). Or, often, it sat on a shelf, untouched, glaring arrogantly at its owner for years. Now, with some guidance and the motivation of a grade hanging in the balance, they hope to slay the beast, or at least land a scratch.

I can relate. I’m among those who tried and failed a few times to read Ulysses before finally getting through the text in its entirety. So as a recovering Ulysses failure, I can speak to the students on their own level of self-loathing, and offer them the sort of encouragement they need to not drop the course after seeing the reading requirements. When I started teaching Ulysses we had eleven-week sessions; then the program was revised to offer eight-week sessions. The book was a bear to teach in eleven weeks, so eight is extra challenging. Yet doable.

We look at two episodes per week, and tackle an inhumane amount of material the penultimate week, episodes 16, 17, and 18; that is, Part III, “Eumaeus,” “Ithaca,” and “Penelope,” some 150 pages—which isn’t unusual in a typical grad course, but it’s 150 pages of Ulysses, capped off by Molly Bloom’s nearly punctuation-free, stream-of-consciousness monologue. To accommodate the move from eleven weeks to eight weeks, I basically cut Part I, the three opening episodes that focus on Stephen Dedalus, and begin in earnest with Leopold Bloom starting his day in Episode 4, “Calypso.” I provide a summary of those opening episodes and encourage students to read them even though they aren’t required per se.

I stress—again and again—that our purpose is not to unlock all the literary mysteries of the novel. Joyce specialists (of which I am decidedly not one) devote whole careers to the book, or only individual episodes. Rather, we want to achieve a basic understanding of what happens in the book, yes, but more importantly we want to lift the hood and see what Joyce was up to in individual episodes, and in the structure of the novel as a whole. In other words, we’re reading the novel as practicing writers, not as literary scholars. I hope to spark an interest in Joyce so that later in life students may feel warm and fuzzy enough about Ulysses to return to it, and to engage with other Joyce texts. Typically I do have a few students who’ve been bitten by the Joyce bug by the end of the session, and they ask for recommendations about where to go next, unaided. Finnegans Wake?, they sometimes ask. God no. I generally recommend Dubliners, and even more specifically “The Dead,” which is available in stand-alone critical editions if a reader is so inclined.

Another piece of advice I offer at the outset: The novel features a cast of thousands, and trying to synthesize all of the characters into your gray matter for easy recall later is probably one of the reading habits that leads to so many normally successful readers giving up in a hailstorm of self-condemnation. Instead, I say, there are just three main characters—Stephen, Bloom, and Molly—so keep an eye out for them. As long as you have a sense of what they do in the novel, from episode to episode, until you reach the Promised Land of “Yes” at the end of 18, then you’re doing just fine.

(We do get into some literary analysis, and one of the aspects we talk about is the novel’s unusually encyclopedic nature, and that Joyce didn’t intend, probably, for it to be read like a typical novel. There’s just too much data to try to hold in one’s head from start to finish. I will admit that in spite of reading the novel from stem to stern at least twice, and some sections multiple times, and even having published about it, plus taught it multiple times, it’s not uncommon for me to read an article or hear a presentation on the novel, and think, “That happens in Ulysses? Really? That sounds interesting.”)

Students are required to write weekly discussion posts based on the episodes, and I give them something concrete to glom onto. I share with them the famous Ulysses schemas, the Gilbert and the Linati, and ask them to write about how two of the elements operate in the week’s readings. Again, I don’t pretend that this an approach that will help them penetrate to the core of the novel’s meaning. Rather, as writers we’re looking at ways that Joyce tried to unify eighteen episodes, or chapters, that use increasingly experimental techniques of storytelling and shift point of view frequently. The schemas are one method, as are the running parallels with Homer’s Odyssey (which are often hard to spot even when one knows to look for them). Another unifying element is Joyce’s attention to chronology, with the narrative unfolding in more or less accurate time over 24 hours. Finally, there is Joyce’s attention to the point of obsession regarding the geography of Dublin in June 1904.

The novel is famous for its stream-of-consciousness narration, which nowadays isn’t exactly revolutionary. Joyce is, however, a master of the technique so a closer examination of almost any episode can lead to a fruitful discussion of how it’s working in detail. “Penelope,” of course, is the example par excellence of interior monologue. To mimic the randomness of one’s thought process, Joyce uses almost no punctuation for more than 30 pages, a section broken into only eight “sentences.” Nevertheless, we can isolate specific thoughts and images. How does Joyce manage it, without the traditional use of punctuation?

Every episode offers a multitude of techniques that could be of value to fiction writers, but in the interest of time here are some approaches that stand out to me.

Episode 4, “Calypso.” The opening three episodes, focused on Stephen Dedalus, establish a realistic chronological approach in the novel, from the start of Stephen’s day at the Martello tower to his meeting with Mr. Deasy to his walk along the strand. Then, abruptly, in this fourth episode time is reset to around 8:00 as we’re introduced to Leopold Bloom. From then on time in the novel unfolds consistently. The lesson: Don’t be afraid to break your own rules.

Episode 6, “Hades.” Bloom takes a carriage ride with three men who are also attending Paddy Dignam’s funeral. Bloom is both part of the group and yet set apart from his companions because of his Jewish heritage and being seen as a quasi-foreigner. This feeling, of being alone in a crowd, is exquisitely human and has obviously been explored by writers and artists throughout history, but no one does it better than Joyce in this iconic episode. The lesson: How to create a character who is both accepted into a social circle while simultaneously being excluded from it.

Episode 7, “Aeolus.” Bloom visits the Freeman newspaper offices, where he has a series of encounters, including with Stephen for the first time in the novel. This episode initiates Joyce’s more overtly experimental techniques as he breaks up the narrative with frequent headline-like insertions throughout. These headlines were a relatively late addition to the episode as it was published without them in The Little Review. Lesson: Don’t be afraid to play with narrative techniques and step from behind the curtain as the storyteller.

Episode 9, “Scylla and Charybdis.” Here Stephen expounds on his theory regarding Shakespeare’s Hamlet in the National Library with a group of fellow literati. His theory has been alluded to previously in the novel. Intertextuality—bringing other texts to bear on the narrative’s primary text—happens frequently in Ulysses. Indeed, Homer’s Odyssey serving as a structural apparatus is itself intertextual. But the use of Hamlet as a well-known literary figure (perhaps the best-known literary figure) to amplify the novel’s own concerns about parent-child relationships, among other issues, is worthy of careful study. Lesson: Bring other texts into conversation with your own narrative.

Episode 10, “Wandering Rocks.” In this scene our attention wanders between a host of different characters and objects. Very little happens in terms of advancing the novel’s plot, but Joyce brings together many of the characters and items of significance we’ve already encountered. Many see this odd episode—with its cinematically sweeping point of view—as a way to tie the earlier (more conventional) chapters of the novel to the later (more experimental) chapters. Lesson: Chapters can have principal objectives other than to advance the plot or evolve characterization; they can serve more purely artistic functions.

Episode 12, “Cyclops.” We join Bloom in Barney Kiernan’s pub, but from the point of view of a new anonymous, first-person narrator. Besides the switch in POV, Joyce also plays with various prose styles, including Irish mythological, legalistic, journalistic, and biblical. This episode, then, breaks two cardinal rules young writers often learn in workshop: to be consistent when it comes to (1) point of view and (2) voice. Without warning, Joyce switches from third- to first-person, and then injects some thirty different prose styles into the telling. Lesson: Know the rules so that you can break them; or, the only rule when it comes to telling a compelling story is that there are no rules.

Episode 14, “Oxen of the Sun.” Joyce takes the technique of Episode 12—the use of multiple prose styles—and goes even further by emulating the evolution of the English language, from its Latin/Germanic roots to Anglo-Saxon to Chaucer to Shakespeare to Defoe to Lamb, and many more. The plot advances at the Holles Street maternity hospital, but it does so via this history of the stages of the English language. Lesson: Have fun. Don’t be afraid to toy with voices and styles within the same piece.

Episode 15, “Circe.” We find ourselves in Nighttown, Dublin’s red-light district, but now the storytelling mode is dramatic. The episode unfolds as a play script, complete with character names and stage directions. The lesson: Go ahead. Begin in one mode and switch to another; then back again, or whatever you feel like doing.

Episode 17, “Ithaca.” Bloom and Stephen walk to Bloom’s residence, an important plot advancement, especially in light of the novel’s Odyssey subtext, but now it’s told via a series questions and answers, resembling, most say, either catechism or Socratic dialogue. Lesson: Why the heck not?

And like Bloom, we return to Episode 18 and No. 7 Eccles Street.

A quick word or two on other kinds of writing assignments one might assign, besides the weekly posts tied to the schemas. For their final project, I have students try their hand at one or more experimental techniques they’ve encountered in the book, creating their own original scene. It’s a two-part assignment. There’s the creative writing itself; then there’s an analytical element in which they identify the episodes and techniques they used as inspiration, quoting and citing from the novel as needed.

In the original eleven-week version of the course, I attempted an ambitious midterm paper. I had students access an episode as it first appeared in either The Little Review or The Egoist (using the Modernist Journals Project online), and compare it to the 1922 book version, identifying Joyce’s revisions and speculating as to why Joyce may have made the changes (almost always additions) that he did. That is, what did he gain through revision? I think it’s a terrific assignment, but, as I say, ambitious, and students were not terribly successful with it. It is perhaps too labor intensive when up against the amount of reading students have to do just to keep pace with the syllabus. So when we went to eight-week sessions, I dropped the assignment. My main purpose was to emphasize the importance of revision and how much care Joyce took in revising his work. I think it’s a potentially fruitful exercise, and maybe given a longer time frame and the right students, it could be a reasonable assignment. (By the way, I did the activity myself, based on Episode 9, “Scylla and Charybdis,” and the brief article was published at Academia Letters—if you want to see an example of what I have in mind with the assignment.)

It’s especially interesting to be teaching Ulysses during its centenary year—an event that will add even more resources from which one might draw (not that there was a shortage previously). If you teach in the right circumstances, I encourage you to consider a course on Ulysses. Or if not that large, loose, baggy monster, maybe another long, challenging text. I’ve thought about War and Peace, but in eight weeks that would be quite a battle. I welcome suggestions.

Preface to ‘Mrs Saville’–2021 Reboot

My novel Mrs Saville was published in 2018, although it had begun to appear two years earlier in serialized installments at Strands Lit Sphere. It was important to me that the book come out in 2018, the bicentennial year of Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, because, as the cover makes plain, Mrs Saville is “a novel that begins where Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein ends.”

I thought it was appropriate homage to the novel, and the author, that inspired my sequel; and I hoped it would be a statement readers would find intriguing. In retrospect, tying Mrs Saville so overtly to Mary Shelley’s classic may have been a marketing misstep. Mrs Saville has been languishing without readers for going on three years — a situation I hope to ease in 2021.

I’ve been teaching Frankenstein for more than twenty years, and I always begin our study by noting that students probably think they know the basic story already, but in fact what they know is a greatly simplified misrepresentation of what Mary Shelley wrote as a profoundly depressed, yet highly motivated, as well as eclectically educated, teenager. The novel was published anonymously in January 1818. In spite of a small initial press run, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus caused an immediate stir among readers and reviewers alike.

Several editions soon followed, as did stage productions that proved highly profitable (not to Mary, however, as modern copyright laws did not yet exist). Beginning with the stage adaptations and continuing with screen adaptations almost the moment cinema was invented (Thomas Edison’s film company produced the first Frankenstein movie, a silent film, in 1910), the novel was reduced to a simplistic horror story about a mute monster terrorizing his creator and anyone unlucky enough to encounter him.

This basic narrative was solidified in the cultural psyche with director James Whales’ wildly popular 1931 movie Frankenstein, and Boris Karloff’s portrayal of the creature (bolts in his neck and all) became emblematic of Mary Shelley’s novel, even though the movie and the monster have little to do with what she created on the page. In the film, Karloff’s creature is an inarticulate fiend, unable to control his emotions and his strength.

The Whales film, like the adaptations that came before and the majority to follow, misrepresented Frankenstein, the novel, as a story about a frightening, out-of-control monster. So, perhaps, my tying Mrs Saville directly to the novel may encourage would-be readers to think my book is just the further exploits of a monster running amok. Such an assumption about Mrs Saville would be as far from the truth as the stage and film adaptations have been from Mary Shelley’s original.

Readers who open the pages of Frankenstein soon find out just how watered-down the story has become in the popular imagination. Scholar Susan J. Wolfson covers the misrepresentation well in her introduction to the Longman Cultural Edition of the 1818 text. Frankenstein is

a vibrant intersection of interlocking cultural concerns: the claims of humanity against scientific exploration; the relationship between ‘monsters’ and their creators; the questionable judgments by which physical difference is termed monstrous; the responsibility of society for the violent behavior of those to whom it refuses care, compassion, even basic decency; the relationships between men and women, and parents and children (and the symbolic version in care-givers and care-receivers); and the psychological dynamics of repression, doubling, and alter egos.

Wolfson’s description accurately represents the novel for which I wrote a sequel. A lot is going on in Frankenstein, and (I like to believe) a lot is going on in Mrs Saville. That said, I don’t want to make my novel out to be a dry, introspective treatise. Far from it. Nor was Mary Shelley’s. Regarding her book’s genesis, she tells us in the introduction to the novel’s 1831 edition:

I busied myself to think of a story; . . . One which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature, and awaken thrilling horror–one to make the reader dread to look around, to curdle the blood, and quicken the beatings of the heart. If I did not accomplish these things, my ghost story would be unworthy of its name.

In writing Mrs Saville, similar goals were foremost in my mind as well. Otherwise, my sequel would be unworthy of its connection to Frankenstein, a book I have loved nearly all of my adult life.

When a reviewer for Kirkus Reviews wrote that Mrs Saville is “a fantastically chilling psychodrama intelligently woven into literary history,” I felt that I had hit my mark. Moreover, in an unsolicited review, the novelist Spenser Stephens said of the book: “The author fits the pieces together with a seamless and terrifying logic. He shows a nuanced understanding of the darkness that lives within us all.”

I was gratified by these early assessments, and further gratified when Mrs Saville began to receive some critical distinctions. It was a quarterfinalist for the ScreenCraft Cinematic Novel Award in 2018, and the same year the novel was a finalist for American Book Fest’s Best Book Award. Then in 2020 Mrs Saville won the Manhattan Book Award in the category of literary fiction.

I felt that the accolades, modest though they be, vindicated the artistic risks I took with the novel. I wanted Mrs Saville to seem an artifact of the same time period and the same place as its impetus; that is, London at the dawn of the nineteenth century. I tried to achieve this effect primarily through two means. Like Mary Shelley’s original, I used an epistolary structure (a novel told via a series of letters). I also imagined Margaret Saville, my narrator, as a woman similar to Shelley in that she was largely self-educated via her own voracious reading.

My novel also needed to be in British English, as opposed to American English, meaning spellings, expressions, punctuation style, syntax, and so forth in the manner that Mary Shelley used in the early 1800s. I found that I had difficulty composing while keeping in mind British English’s differences from modern American English, so I decided to write the first drafts as I was accustomed to writing; then to convert my Americanisms into nineteenth-century British vernacular in the processes of revising and editing. I found, then, that the unfamiliar style didn’t impede my creativity.

In spite of the work I’d put into writing Mrs Saville, and its good reviews and modest accomplishments, finding readers for the book has proven a considerable challenge. I wasn’t able to capitalize on its winning the Manhattan Book Award to any great extent because I was notified of the prize in the summer of 2020, when the pandemic was peaking again. Furious debates were raging everywhere about opening up businesses, etc., and whether or not schools should open in August. Everyone, including me, was distracted by weightier matters than a novel’s winning a prize.

I promoted Mrs Saville on social media, and I purchased advertisements here and there (spending more money than I care to recall . . . in the thousands of dollars), but none of it accomplished much as far as attracting readers. Nearly every writer is facing this challenge. It is estimated that more than 3 million books are published each year, and yet only a handful of authors account for the vast majority of books sales, according to EPJ Data Science.

Writers trying to build a readership face a classic catch-22: Librarians and bookstore managers are reluctant to devote shelf space to an author that readers don’t recognize; and readers don’t recognize these authors because librarians and bookstore managers are reluctant to devote shelf space to them.

So, instead of relying on social media and costly advertising, for this promotional reboot I’m targeting book clubs in hopes of getting Mrs Saville directly into the hands of readers. From the start, however, there’s an obstacle. Book clubbers don’t tend to buy books, preferring to borrow them from libraries — therefore, if libraries haven’t acquired your title, book clubs will most likely pass.

To overcome this obstacle, I’m happy to send interested book clubs copies of Mrs Saville. I’d much rather spend money on getting my books out into the world, as opposed to buying a few meager inches of expensive and inconsequential advertising space. Moreover, I’ll be happy to speak with groups, in person or via Skype or Zoom, etc. I’m happy to do readings and interviews — essentially anything to connect with potential readers.

Here is the novel’s description:

Margaret Saville’s husband has been away on business for weeks and has stopped replying to her letters. Her brother, Robert Walton, has suddenly returned after three years at sea, having barely survived his exploratory voyage to the northern pole. She still grieves the death of her youngest child as she does her best to raise her surviving children, Felix and Agatha. The depth of her brother’s trauma becomes clear, so that she must add his health and sanity to her list of cares. A bright spot seems to be a new friendship with a young woman who has just returned to England from the Continent, but Margaret soon discovers that her friend, Mary Shelley, has difficulties of her own, including an eccentric poet husband, Percy, and a book she is struggling to write. Margaret’s story unfolds in a series of letters to her absent husband, desperate for him to return or at least to acknowledge her epistles and confirm that he is well. She is lonely, grief-stricken and afraid, yet in these darkest of times a spirit of independence begins to awaken. ‘Mrs Saville’ begins where Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’ ends. The paperback edition includes the short story “A Wintering Place” and an Afterword by the author.

It’s important to note that even though Mrs Saville is a sequel to Frankenstein, it’s not necessary to have read Frankenstein in order to understand and (I trust) enjoy my novel.

Anyone interested in talking with me about using Mrs Saville for their book club or another literary function, please contact me through my website — tedmorrissey.com — or email me, jtedmorrissey [at] gmail [dot] com.

I’ve always written, and I’ve always written in the same state as most writers — largely without readers. I will always write, but some readers would be nice.

Preface to ‘First Kings and Other Stories’

I am delighted that Wordrunner eChapbooks has brought out First Kings and Other Stories, which functions on multiple levels. It is, as the title implies, a collection of stand-alone stories. The stories are interconnected, though, and work together as an independent novella. They also represent a work in progress–a novel that takes place over a 24-hour period in 1907 (as I am envisioning it now).

This larger work in progress is a further evolution of a concept I experimented with in my novel Crowsong for the Stricken (2017), in that each piece was designed to work on the microcosmic as well as the macrocosmic level, meaning that each piece could be read as a fully realized short story while also contributing a vital piece to the macrocosm of the novel. Crowsong was mainly set in 1957, in an isolated, unnamed Midwestern village, but the narrative structure is deliberately indeterminate. That is, my hope was that readers would encounter the twelve pieces in an order of their own choosing. The various possible combinations would change the reader’s experience of the novel as a whole. I called it a “prismatic novel” for this reason.

I am trying to take the idea further in this current work in progress. Similar to Crowsong, each piece is intended to function on both the micro- and macrocosmic levels, but the structure is much tighter, both in terms of narrative timing and in the number of interlocking pieces. It is challenging. Not infrequently, when writing, I think of a plot advancement or some other detail that would work quite nicely in the limited world of the short story, but it would throw off, or even contradict, something in the more expansive world of the novel of which it is also part. At the same time, the connective tissue I’m building within each piece so that it harmonizes with the whole must fit seamlessly in the short story, too.

So far it seems to be working. The title story, “First Kings,” appeared originally in North American Review and was reprinted in Sequestrum. The second piece, “Hosea,” was published by Belle Ombre. Quite honestly, it was the third story, “The Widow’s Son,” that prompted me to send the entire manuscript (as it stood at the time) to Wordrunner when they put out a call for novella-length submissions. “The Widow’s Son,” at just over 8,300 words, is about twice as long as either “First Kings” or “Hosea,” and its length would make it a difficult placement with literary journals. Once one writes beyond 5,000 words it becomes increasingly difficult to place. I had only just begun to circulate “The Widow’s Son,” to one or two places, when I saw the Wordrunner notice.

Wordrunner responded promptly, and publication was scheduled for December 2020. In the intervening months I continued the work in progress, mainly producing one new piece, “The Buzite.” I mentioned it to Jo-Anne Rosen, the editor with whom I was working at Wordrunner, but I felt trying to include it in the First Kings collection would throw the three pieces out of balance. I think I was right about that, so “The Buzite” is currently making the literary-journal rounds (as is another brand-new, somewhat fragmentary piece, “The Appearance of Horses”).

It has been a wonderfully rewarding experience working with Jo-Anne Rosen and Wordrunner. One issue we discussed has to do with the pieces’ titles, which are obviously derived from the Bible. Yet the connections between the titles and their stories isn’t crystal clear. Jo-Anne was in favor of adding epigraphs to each story in an attempt to connect the dots, so to speak, for readers. I tend to like epigraphs in my books, so I was open to the idea and tried to find some suitable quotes from the Bible. It proved harder than I imagined. I didn’t much like any of the quotes I came up with for their stories, but suggested a compromise whereby we would use one as an epigraph for the collection as a whole. Jo-Anne wisely, and diplomatically, demurred.

The problem, I discovered, is that the biblical associations are deliberately abstract and multifaceted, and trying to pin an epigraph to the stories forced a more limited and more concrete connection. I very much believe in the notion that interpreting a piece of writing is a partnership between writer and reader. When it comes to finding associations between the biblical references and the texts of the narratives, I prefer for readers to have free imaginative rein. I obviously have something in mind, but I believe readers could come up with cleverer and more interesting ideas. It’s one of the joys of reading, after all.

Writing a novel–or any long work, imaginative or otherwise–can be a lonely business. It requires countless hours of being alone, to write, to research, to think, to wonder. I like to have some human contact regarding the work along the way, which is why I send out pieces as a work progresses. The editors who see fit to publish them provide more encouragement than they can know. Wordrunner eChapbooks’ publishing First Kings and Other Stories has provided me a great deal of satisfaction as well as artistic fuel. It will be years yet before the larger work is complete, but all the editors who will have helped it along the way are invaluable to the process and truly appreciated

First Kings and Other Stories is available via Smashwords, Kindle, and at the Wordrunner site. Visit the book’s site at my author page, and access the sell sheet here.

Preface to ‘The Artist Spoke’

Like all novels, The Artist Spoke is about many things — some that I, as the author, am privy to, and some, as the author, I am not. One of the things it’s about (I know) is what it means to be a writer when the book, as an art form, is gasping its final breaths. Why labor over a novel, a story, a poem, an essay when you’re certain almost no one is going to read it?

It’s a question I’ve been contemplating, on various levels, for a number of years — as a writer certainly, but also as a publisher, a teacher, a librarian, and a reader. I have found solace in the words of my literary idol William H. Gass: “Whatever work [the contemporary American writer] does must proceed from a reckless inner need. The world does not beckon, nor does it greatly reward. . . . Serious writing must nowadays be written for the sake of the art.”

Gass shows up, explicitly, a couple of times in The Artist Spoke. I use most of the above quote as an epigraph for Part II of the novel, “Americana.” Then later, the two main characters, Chris Krafft and Beth Winterberry, visit a bookstore where they briefly discuss Gass’s iconic essay collection Fiction and the Figures of Life and specifically its concluding piece “The Artist and Society.” I read the essay often, as a reminder — a kind of mantra — that what I do, answering the call of the “reckless inner need,” is not only worthwhile but important.

Quoting the Master again: “[The world] does not want its artists, after all. It especially does not want the virtues which artists must employ in the act of their work lifted out of prose and paint and plaster into life.” Gass goes on to discuss these virtues, which include honesty, presence, unity, awareness, sensuality, and totality (that is, “an accurate and profound assessment of the proportion and value of things”).

Gass concludes the essay, written toward the end of the 1960s (the Vietnam era), by saying that “the artist is an enemy of the state [. . . but also] an enemy of every ordinary revolution [. . . because] he undermines everything.” That is, to be true to their art, artists must be ready to stand alone. As soon as they lend their voice to a cause, their art becomes something else, like propaganda, jingoism, a corporate slogan.

The Artist Spoke is a departure for me in several ways. For one, it has a contemporary setting. When I began writing the novel, in late 2015 or early 2016, I even intended for it to have a somewhat futuristic setting — but when it takes five years to write a novel nowadays, the future quickly becomes the now, if not the past. My other novels and novellas have been set in the past: Men of Winter (early twentieth century, First World War-ish), Figures in Blue (also early twentieth century), Weeping with an Ancient God (July 1842), An Untimely Frost (1830s), Crowsong for the Stricken (1950s, mainly), and Mrs Saville (1816 or 17).

I prefer writing in a past setting. My current project is set in 1907 (the first three episodes are going to be published by Wordrunner as an e-novella or abbreviated collection, First Kings and Other Stories). I like the definitiveness of the past, and I enjoy reading history — so doing research is one of the most pleasurable parts of the writing process. What rifle would the hunter have been using? When did electricity come to that part of the country? How were corpses embalmed?

Though a devout atheist, I’m fascinated with the Bible, as a narrative and as a cultural artifact, so I often incorporate biblical elements into my fiction. I did this to some degree in Crowsong for the Stricken, but in the current project all the stories (episodes?) are rooted in Bible stories and biblical imagery, which is reflected in their titles: “First Kings,” “Hosea,” “The Widow’s Son,” and (the newest) “The Buzite.”

Religious faith is explored in The Artist Spoke as well. For instance, the novel asks, is faith in literature — or devotion to a particular author — not a kind of religion, and one that could be more meaningful than a traditional religion? A faith’s liturgy, after all, is at the core of its beliefs (in theory). Are not Joyceans, then, a kind of congregation? People who consider life’s meaning through the lenses of Ulysses or Finnegans Wake or another Joyce text, like “The Dead”?

For me, though a fan and admirer of Joyce, my religion is rooted in the writings of William H. Gass. They help me to understand the world and to sort through my own opinions and feelings regarding what the world offers up to me, like a pandemic, like a country where many of its citizens refuse to take precautions against spreading the virus, believing it to be some sort of hoax or conspiracy. Gass said, “One of the themes of my work is that people certainly do not want to know the truth, and they construct all sorts of idiocies to avoid facing it.” Amen.

Reading Gass helps me to cope with what is going on in the country right now. I would want that sort of solace for anyone, for everyone — but one needs to read literature and read it well and read it often. And those days are quickly coming to an end.

Another way that The Artist Spoke is a departure for me is that I feel I have stepped from behind a curtain to acknowledge that the book is all me: I wrote it, I took the photographs, I designed the book, I designed the cover, I edited it. I have done everything. I have been slowly inching my way into full view. With my last book, Mrs Saville, I was essentially out but was perhaps not quite as vocal about it.

Self-publishing is still seen by many as “vanity publishing.” In other artistic fields, taking charge of your own art is viewed as rebellious and bold: musicians who create their own labels, fashion designers who found their own boutiques, visual artists who start their own galleries, etc. The simple truth is that commercial publishing houses are not interested in what I’m doing in my writing, thus literary agents aren’t either. Nevertheless, I still feel that “reckless inner need”; and, what is more, I enjoy the entire process. I love writing the stories and novels, and I enjoy designing the books and illustrating them.

By taking control of the whole process, I can shape the book into a unified artistic expression. The design can complement the words. I’ve had run-ins over the years with editors, and I’ve been disappointed by the efforts of graphic designers who didn’t seem to get my work (perhaps they didn’t read it, or comprehend it).

That said, I do have an ego, so I seek publication for pieces of my books as I work on them (perhaps I am more sensitive to the charge of vanity publishing than I like to let on). Most of The Artist Spoke appeared in print, here and there, prior to the novel’s full publication, in Floyd County Moonshine, Lakeview Journal, Adelaide Magazine, Central American Literary Review, and Litbreak Magazine. I say in the Acknowledgments, “I wrote this book in fits and starts, often losing my way, at one point abandoning it for nearly two years. The editors who saw something of value in the work and published pieces of it over time provided more encouragement than they can know.”

My ego also hopes at least a few people read and enjoy The Artist Spoke, but I didn’t write it for a mass audience. Ultimately, I suppose, I wrote it for an audience of one. In any case, I give it to the world, to take or to leave. Gass-speed, little book.

Jailbreak!: William Gass’s Lifelong Work to Free Himself from the Imprisonment of Print

This paper was presented at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture Since 1900, University of Louisville, on February 23, 2018. Due to a last-minute change, I chaired the panel, Temporalities of Revision. Other panelists were Kelly Kiehl, University of Cincinnati; and Sarah-Jordan Stout, Rice University. The paper is dedicated to William H. Gass, who passed away December 6, 2017.

In the annals of American experimental fiction, William H. Gass’s Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife holds a place of reverence due, mainly, to its ambitious (some may say, excessive) experimentation: nineteen different typefaces (varying in point sizes, with unusual placements and movements on the pages), and copious graphic elements, including several photos of a nude model. The odd little novella first appeared in 1968 as TriQuarterly supplement No. 2 – in its most experimental format, which included a variety of paper stock in addition to its other eccentricities – then in a hardcover edition from Knopf (1971) and later a paperback edition from Dalkey Archive (1989). The Knopf and Dalkey editions maintained the original design, minus the use of various paper stock.

Willie Masters’ occupies a place of infamy in Postmodern circles: No one faults Gass’s ambitions. However, the odd little book hasn’t garnered much, well, affection over the years either, which I think is a crying shame. Even Gass himself wasn’t overly generous regarding the end result. In the Art of Fiction interview (1976) he stated,

I was trying out some things. Didn’t work. Most of them didn’t work. . . . Too many of my ideas turned out to be only ideas—situations where the reader says: “Oh yeah, I get the idea,” but that’s all there is to get, the idea. I don’t give a shit for ideas—which in fiction represent inadequately embodied projects—I care only for affective effects. (Conversations 22)

He was, I think, a little too hard on himself. I am moved by the book; it affects me, but perhaps not quite as Gass would have hoped. And Gass may have changed his opinion of Willie Masters’ success over time. In the essay “Anywhere but Kansas” which first appeared in The Iowa Review in 1994 (nearly thirty years after writing Willie Masters’ and on the cusp of The Tunnel’s publication, which required a gestation of nearly that length of time and which makes use of many of the techniques in its infamous predecessor), Gass discusses the importance of experimentation: “An experiment, I would learn much later, . . . had to arise from a real dissatisfaction with existing knowledge. There was a gap to be filled, a fracture to be repaired, an opening to be made” (29). The public at large, he says, only admires experiments that work; however, for the experimenters themselves, an unsuccessful experiment may bring its own kind of success. “In the lab,” writes Gass, “a ‘no’ may not elicit cheers; it is nevertheless a bearer of important information” (30). He may, then, have learned some important narrative lessons from Willie Masters’, lessons he took to heart during the three decades he labored on The Tunnel, which shares some of Willie Masters’ techniques, but significantly toned down.

What is more, three decades later, Gass felt just as strongly about the need for writers to engage in experimentation for the sake of their art: “[I]t is . . . repeatedly necessary for writers to shake the system by breaking its rules, ridiculing its lingo, and disdaining whatever is in intellectual fashion. To follow fashion is to play the pup” (Conversations 30). Gass may not have achieved the aesthetic affects he was aiming for in Willie Masters’ in 1968, but, in retrospect, he seemed to value his own efforts — though he doesn’t say so explicitly.

What is more, three decades later, Gass felt just as strongly about the need for writers to engage in experimentation for the sake of their art: “[I]t is . . . repeatedly necessary for writers to shake the system by breaking its rules, ridiculing its lingo, and disdaining whatever is in intellectual fashion. To follow fashion is to play the pup” (Conversations 30). Gass may not have achieved the aesthetic affects he was aiming for in Willie Masters’ in 1968, but, in retrospect, he seemed to value his own efforts — though he doesn’t say so explicitly.

As wildly experimental as Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife turned out to be, it was tamer than Gass had in mind1. A visit to the Gass Papers at Washington University in St. Louis, where Gass taught philosophy from 1969 to 1999, can give us some sense of what the author had in mind from the start, working only with a manual typewriter, pen or pencil, straight edge, scissors and glue, plus other objects like fabric and newspaper clippings. In part what Gass was trying to achieve was bridging the gap between writer and reader by making the narrative come to life, so to speak, in the reader’s hands. That is, rather than simply describing things — that is, providing symbols for things — which evoke intellectual and (hopefully) emotional responses in the reader, Gass wanted the thing itself to become part of the reader’s world. In essence, the book itself becomes a performance piece in the reader’s world — akin perhaps to the playwright’s task in moving from script to performed play. One writes of a pistol on the page, which becomes a real pistol on the stage, one which discharges so that the audience members can actually hear its bang and actually smell its smoke.

Gass may encourage this comparison by including a play as one of the multiple narratives at work in Willie Masters’, whose overarching narrative is Babs Masters’ seduction of the reader into her lonely text. One of the best examples of Gass’s attempt to move from manuscript into the reader’s reality is via a set of coffee-cup rings that appear on several pages. A new section of the novella begins, “The muddy circle you see just before you and below you represents the ring left on the leaf of the manuscript by my coffee cup” ([37]). But just as the theatrical pistol is only a prop, Gass immediately acknowledges that the dark-brown circle is not actually a ring from his cup: “Represents, I say, because, as you must surely realize, this book is many removes from anything I’ve set pen, hand, or cup to.” The author attempts to enter the reader’s reality more corporeally than authors typically do, but, ultimately, that gap can only be bridged so far.

We can see that the coffee-ring idea was an early one in Gass’s conception of the book, and, in fact, was created no doubt by actual coffee.2 The circle returns later in the novella, but in a more metaphorical role according to the text it encircles: “This is the moon of daylight” ([52]). The circle multiplies to appear as five circles on the final two pages of the book, in two cases highlighting the inserted phrases “HERE BE DRAGONS” and “YOU HAVE FALLEN INTO ART — RETURN TO LIFE” ([58]). The final coffee-like ring appears on the facing page, which is a close-up of the female nude’s breasts and navel, with the ring encircling the latter.3 Others have noted that there are (at least) two female models used for the book: one whose image appears on the cover, and another whose images appear (possibly) eight times throughout the book. The final coffee ring appears on the torso of, it appears, the cover’s model. The interior version of Babs Masters is more, well, voluptuous than the cover and final coffee-ring Babs. Yet there is a striking difference between the cover and the final image: The nude on the cover has no belly-button; it’s been airbrushed out. The final coffee-ring encircles and emphasizes the belly-button, however, maybe making us take note of its absence on the cover.

Is it in fact, then, Babs represented on the cover of the book, or is it Eve? Gass would go on to use Eve as a metaphor with regularity in his fictions. Michael Hardin makes some provocative observations about Willie Masters’ in an article in Short Story, discussing both Gass’s novella and Kathy Acker’s New York City in 1979. Hardin notes, for example, that on the first page of the book Babs’s hand reaches toward the title just as the reader does in a rather hand-of-God sort of way:

The extended arm references Michelangelo’s Creation of Man, where God is extending his hand to spark life into Adam’s extended hand. The reader must decide whether Babs (the wife) is in the space of the creator or the created. . . . [G]iven the nature of the sexual politics of the text, one might argue that Babs is the creative spark passed between author (whose hand reaches out with the pen) and reader, God and Adam. (80-81)

Perhaps Hardin didn’t notice the MIA belly-button because he doesn’t bring Eve into the analysis even though it seems rife for her inclusion. By encircling Babs’s navel at the conclusion of the book (and returning to the cover model for the image), Gass signals that Eve/Babs is now only Babs, making the statement “You have fallen into art—return to life” especially provocative. It may be that our sojourn in the complicated text of Willie Masters’ – which Gass overtly parallels with our having sexual intercourse with Babs – is akin to the Fall, and when we reach the final page we are expelled from the textual Paradise, like hapless Adam and Eve; however, like Adam and Eve we have acquired a unique experience for which we are the richer, even if that richness is colored by sin. But since sin in this metaphor is art/sex, Gass implies sin ain’t such a bad thing, and, in fact, it (art, experiencing it, creating it) is the only thing that makes life worth living: An idea which Gass returned to again and again in his fiction, his essays, his criticism, and his interviews. In addition to being a voracious and eclectic reader, Gass said, in 1971, that he enjoyed “all” the arts, “especially perhaps ballet (when pure and not mucked up) and architecture. I was an opera nut when young. . . . I haunt museums when I can. In one sense, painting has influenced my theory of art more than almost anything, music my practice of it” (9). Gass’s interest in the visual is obviously reflected in his merging of text with pictorial elements. As a writer, he was about what all writers ought to be about, he said: “You are advancing an art—the art. That is what you are trying to do” (26).

Perhaps Hardin didn’t notice the MIA belly-button because he doesn’t bring Eve into the analysis even though it seems rife for her inclusion. By encircling Babs’s navel at the conclusion of the book (and returning to the cover model for the image), Gass signals that Eve/Babs is now only Babs, making the statement “You have fallen into art—return to life” especially provocative. It may be that our sojourn in the complicated text of Willie Masters’ – which Gass overtly parallels with our having sexual intercourse with Babs – is akin to the Fall, and when we reach the final page we are expelled from the textual Paradise, like hapless Adam and Eve; however, like Adam and Eve we have acquired a unique experience for which we are the richer, even if that richness is colored by sin. But since sin in this metaphor is art/sex, Gass implies sin ain’t such a bad thing, and, in fact, it (art, experiencing it, creating it) is the only thing that makes life worth living: An idea which Gass returned to again and again in his fiction, his essays, his criticism, and his interviews. In addition to being a voracious and eclectic reader, Gass said, in 1971, that he enjoyed “all” the arts, “especially perhaps ballet (when pure and not mucked up) and architecture. I was an opera nut when young. . . . I haunt museums when I can. In one sense, painting has influenced my theory of art more than almost anything, music my practice of it” (9). Gass’s interest in the visual is obviously reflected in his merging of text with pictorial elements. As a writer, he was about what all writers ought to be about, he said: “You are advancing an art—the art. That is what you are trying to do” (26).

One of Gass’s ambitions in Willie Masters’ is to seduce the reader into reading the text carefully and thoughtfully – that is, deeply. Already in 1966, when he began work on the novella, Gass recognized that too many readers were impatiently speeding through texts, and (worse perhaps) too many writers were providing them material that enabled such shallow encounters. Gass said, “A lot of modern writers . . . are writing for the fast mind that speeds over the text like those noisy bastards in motor boats. . . . They stand to literature as fast food to food” (25). Whenever one begins unpacking a Gass metaphor, the act, by necessity, becomes reductive. Nevertheless, for illustration’s sake, I’ll work my way through Gass’s attempted seduction of the reader in Willie Masters’ via his use of metaphor, wordplay, and imagery. I will force myself as best I can to hold onto a single strand and resist the text’s Siren song which could lead us in myriad directions (not to our doom, however).

One of several storylines Gass juggles in Willie Masters’ is a playscript featuring Ivan and Olga wherein Ivan finds a penis baked into his breakfast roll. At this point in the novella the carnival ride hasn’t become too topsy-turvy for the reader, but it’s about to begin spinning (nearly) out of control. Gass starts interrupting the playscript with footnotes which engage the reader in academic-sounding notes related, it seems, to the main narrative. The first footnote is signaled by an asterisk, and the second by two asterisks (just as Gass is using asterisks to represent other things in the text besides footnotes, so are these footnotes after all? — Or is Gass toying with us?). The second alleged footnote references John Locke’s Concerning Human Understanding (ha!) and discusses how “ideas” are “take[n] in,” “masticate[d]” and “swallow[ed] down” ([15], my emphasis on down). The footnote-like interruptions continue on the following pages, except on page [17] the footnote itself is interrupted with yet another typeface, in bold, which says, “Now that I’ve got you alone down here [i.e., at the bottom of the page], you bastard, don’t think I’m letting you get away easily, no sir, not you brother; anyway, how do you think you’re going to get out, down here where it’s dark and oily like an alley . . . ?” Suddenly “down here” is not the bottom of the page, but rather it’s Babs talking to us about her dark and oily sex, which she says is as “meaningless as Plato’s cave.” We, the blissful readers, have been lured there, in between Babs’s waiting legs, and there’s no easy way out.

The complexities mount, so to speak, for twenty or more pages before we come (ugh) to the section that introduces us to the “muddy circle” — whose dark shape, like the opening of Plato’s cave perhaps, has even more symbolic weight than mere coffee-cup ring. We also note that the section begins with Babs’s bare leg and foot knocking down the enlarged “T” in “The” with which the paragraph starts, thus echoing the earlier seductive “footnote” ([37]). Gass’s playing with the convention of the footnote, a standard feature of annotated texts, appears to contradict its function, at first, but upon further contemplation (and multiple readings) it does not contradict it. That is, normally a footnote aids in clarifying a reference, and thereby maybe an entire passage, but the footnotes in Willie Masters’ seem to only muddy the narrative waters, obscuring instead of clarifying. However, we later realize that the footnotes are aiding our understanding of the novella as a whole, contributing to the convention that Gass is attempting to seduce us into a complex relationship with his book. Intercourse with Babs Masters cannot be a mere one-night stand; she gets into your head and won’t let you go — à la Fatal Attraction. (Luckily I don’t have a pet rabbit.)

The complexities mount, so to speak, for twenty or more pages before we come (ugh) to the section that introduces us to the “muddy circle” — whose dark shape, like the opening of Plato’s cave perhaps, has even more symbolic weight than mere coffee-cup ring. We also note that the section begins with Babs’s bare leg and foot knocking down the enlarged “T” in “The” with which the paragraph starts, thus echoing the earlier seductive “footnote” ([37]). Gass’s playing with the convention of the footnote, a standard feature of annotated texts, appears to contradict its function, at first, but upon further contemplation (and multiple readings) it does not contradict it. That is, normally a footnote aids in clarifying a reference, and thereby maybe an entire passage, but the footnotes in Willie Masters’ seem to only muddy the narrative waters, obscuring instead of clarifying. However, we later realize that the footnotes are aiding our understanding of the novella as a whole, contributing to the convention that Gass is attempting to seduce us into a complex relationship with his book. Intercourse with Babs Masters cannot be a mere one-night stand; she gets into your head and won’t let you go — à la Fatal Attraction. (Luckily I don’t have a pet rabbit.)