Preface to ‘The Artist Spoke’

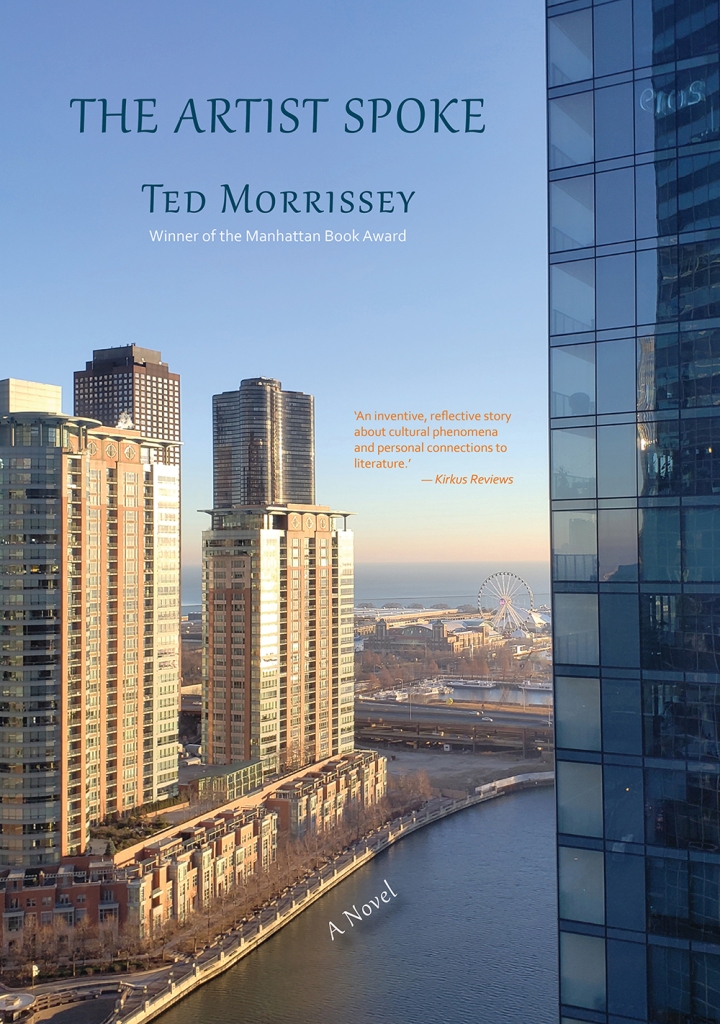

Like all novels, The Artist Spoke is about many things — some that I, as the author, am privy to, and some, as the author, I am not. One of the things it’s about (I know) is what it means to be a writer when the book, as an art form, is gasping its final breaths. Why labor over a novel, a story, a poem, an essay when you’re certain almost no one is going to read it?

It’s a question I’ve been contemplating, on various levels, for a number of years — as a writer certainly, but also as a publisher, a teacher, a librarian, and a reader. I have found solace in the words of my literary idol William H. Gass: “Whatever work [the contemporary American writer] does must proceed from a reckless inner need. The world does not beckon, nor does it greatly reward. . . . Serious writing must nowadays be written for the sake of the art.”

Gass shows up, explicitly, a couple of times in The Artist Spoke. I use most of the above quote as an epigraph for Part II of the novel, “Americana.” Then later, the two main characters, Chris Krafft and Beth Winterberry, visit a bookstore where they briefly discuss Gass’s iconic essay collection Fiction and the Figures of Life and specifically its concluding piece “The Artist and Society.” I read the essay often, as a reminder — a kind of mantra — that what I do, answering the call of the “reckless inner need,” is not only worthwhile but important.

Quoting the Master again: “[The world] does not want its artists, after all. It especially does not want the virtues which artists must employ in the act of their work lifted out of prose and paint and plaster into life.” Gass goes on to discuss these virtues, which include honesty, presence, unity, awareness, sensuality, and totality (that is, “an accurate and profound assessment of the proportion and value of things”).

Gass concludes the essay, written toward the end of the 1960s (the Vietnam era), by saying that “the artist is an enemy of the state [. . . but also] an enemy of every ordinary revolution [. . . because] he undermines everything.” That is, to be true to their art, artists must be ready to stand alone. As soon as they lend their voice to a cause, their art becomes something else, like propaganda, jingoism, a corporate slogan.

The Artist Spoke is a departure for me in several ways. For one, it has a contemporary setting. When I began writing the novel, in late 2015 or early 2016, I even intended for it to have a somewhat futuristic setting — but when it takes five years to write a novel nowadays, the future quickly becomes the now, if not the past. My other novels and novellas have been set in the past: Men of Winter (early twentieth century, First World War-ish), Figures in Blue (also early twentieth century), Weeping with an Ancient God (July 1842), An Untimely Frost (1830s), Crowsong for the Stricken (1950s, mainly), and Mrs Saville (1816 or 17).

I prefer writing in a past setting. My current project is set in 1907 (the first three episodes are going to be published by Wordrunner as an e-novella or abbreviated collection, First Kings and Other Stories). I like the definitiveness of the past, and I enjoy reading history — so doing research is one of the most pleasurable parts of the writing process. What rifle would the hunter have been using? When did electricity come to that part of the country? How were corpses embalmed?

Though a devout atheist, I’m fascinated with the Bible, as a narrative and as a cultural artifact, so I often incorporate biblical elements into my fiction. I did this to some degree in Crowsong for the Stricken, but in the current project all the stories (episodes?) are rooted in Bible stories and biblical imagery, which is reflected in their titles: “First Kings,” “Hosea,” “The Widow’s Son,” and (the newest) “The Buzite.”

Religious faith is explored in The Artist Spoke as well. For instance, the novel asks, is faith in literature — or devotion to a particular author — not a kind of religion, and one that could be more meaningful than a traditional religion? A faith’s liturgy, after all, is at the core of its beliefs (in theory). Are not Joyceans, then, a kind of congregation? People who consider life’s meaning through the lenses of Ulysses or Finnegans Wake or another Joyce text, like “The Dead”?

For me, though a fan and admirer of Joyce, my religion is rooted in the writings of William H. Gass. They help me to understand the world and to sort through my own opinions and feelings regarding what the world offers up to me, like a pandemic, like a country where many of its citizens refuse to take precautions against spreading the virus, believing it to be some sort of hoax or conspiracy. Gass said, “One of the themes of my work is that people certainly do not want to know the truth, and they construct all sorts of idiocies to avoid facing it.” Amen.

Reading Gass helps me to cope with what is going on in the country right now. I would want that sort of solace for anyone, for everyone — but one needs to read literature and read it well and read it often. And those days are quickly coming to an end.

Another way that The Artist Spoke is a departure for me is that I feel I have stepped from behind a curtain to acknowledge that the book is all me: I wrote it, I took the photographs, I designed the book, I designed the cover, I edited it. I have done everything. I have been slowly inching my way into full view. With my last book, Mrs Saville, I was essentially out but was perhaps not quite as vocal about it.

Self-publishing is still seen by many as “vanity publishing.” In other artistic fields, taking charge of your own art is viewed as rebellious and bold: musicians who create their own labels, fashion designers who found their own boutiques, visual artists who start their own galleries, etc. The simple truth is that commercial publishing houses are not interested in what I’m doing in my writing, thus literary agents aren’t either. Nevertheless, I still feel that “reckless inner need”; and, what is more, I enjoy the entire process. I love writing the stories and novels, and I enjoy designing the books and illustrating them.

By taking control of the whole process, I can shape the book into a unified artistic expression. The design can complement the words. I’ve had run-ins over the years with editors, and I’ve been disappointed by the efforts of graphic designers who didn’t seem to get my work (perhaps they didn’t read it, or comprehend it).

That said, I do have an ego, so I seek publication for pieces of my books as I work on them (perhaps I am more sensitive to the charge of vanity publishing than I like to let on). Most of The Artist Spoke appeared in print, here and there, prior to the novel’s full publication, in Floyd County Moonshine, Lakeview Journal, Adelaide Magazine, Central American Literary Review, and Litbreak Magazine. I say in the Acknowledgments, “I wrote this book in fits and starts, often losing my way, at one point abandoning it for nearly two years. The editors who saw something of value in the work and published pieces of it over time provided more encouragement than they can know.”

My ego also hopes at least a few people read and enjoy The Artist Spoke, but I didn’t write it for a mass audience. Ultimately, I suppose, I wrote it for an audience of one. In any case, I give it to the world, to take or to leave. Gass-speed, little book.

The Loss of the Literary Voice and Its Consequences

The following paper was presented at the MLA International Symposium in Lisbon, Portugal, July 23-25, 2019, on “Remembering Lost Voices.” The panel was titled “The Reading Public: Recovering Reader Experiences and Agency.” Other papers were “Recovering the Lost Voices of Nonprofessional Readers” by Tomas Oliver Beebee, Penn State; “Unplugged Reading: Digital Disconnect as a Form of Resistance” by Cátia Ferreira, Católica Portuguesa; and “Recovering Voices Lost: The Reader-Listener as Secondary Witness” by Eden Wales Freedman, Mount Mercy. Helen Groth, New South Wales, served as (impromptu) chair and discussant.

Be forewarned: This paper likely proposes more questions than it offers anything remotely resembling solutions. But as we know framing the proper questions, or framing the questions properly, is a necessary step in any process which hopes to advance some positive effect. Much of this paper is based on the writings and observations of American author William H. Gass (1924-2017), of whom I’ve been a devotee (some may say “disciple”) for a decade. In 1968, at the height of Vietnam War protests, Gass published the essay “The Artist and Society,” in which he states “[naturally] the artist is an enemy of the state . . . [who] is concerned with consciousness, and he makes his changes there.” He goes on to say that “[artful] books and buildings go off under everything—not once but a thousand times” (287, 288). Then Gass asks, “How often has Homer remade men’s minds?” That is, Gass seemed to believe that artists, including literary artists like himself, could have a profound impact on society, enough of an impact to sway governments from one policy position to another, through the sheer force of their art. Reading his words and others’, and taking in other forms of art, could, in fact, alter human consciousness.

Gass of course was hardly alone in this observation, and it may have been believable in 1968 when the Counterculture, led by the United States’ youth and the country’s intellectuals, were reshaping public opinion on the war in Southeast Asia. But changes were already afoot that would undercut the reformative powers of literature, and Gass’s optimism for that matter. In retrospect we can see that many such changes were afoot by the late sixties, but in this paper I want to concern myself chiefly with two: the corporate takeover of the publishing industry, and the coming of age of the Internet and, with it, social media.1

Indeed, Gass’s change of heart, from one of optimism to one of pessimism, can be seen in the preface he wrote in 1976 for the re-release of his seminal story collection In the Heart of the Heart of the Country (1968): “The public spends its money at the movies. It fills [sports] stadia with cheers; dances to organized noise; while books die quietly, and more rapidly than their authors. Mammon has no interest in their service” (xiii). He continues, “The contemporary American writer is in no way a part of the societal and political scene. He is therefore not muzzled, for no one fears his bite; nor is he called upon to compose” (xviii). So in less than a decade, Gass went from suggesting that literature could remake human consciousness and reform government policy, to believing that serious writing had no impact on society whatsoever.

What the heck happened?

One of the things that happened was the corporate takeover of the publishing industry. The process was largely undocumented when André Schiffrin wrote The Business of Books (2000). “In Europe and in America,” writes Schiffrin, “publishing has a long tradition as an intellectually and politically engaged profession. Publishers have always prided themselves on their ability to balance the imperative of making money with that of issuing worthwhile books” (5). However, in the turbulent sixties, large conglomerates began acquiring publishing houses. Schiffrin continues, “It is now increasingly the case that the owner’s only interest is in making money and as much as possible” (5, emphasis in original). Schiffrin’s study is wide-ranging and thorough, but he focuses particular attention on the demise of Pantheon, where he’d been managing director for a number of years when it was acquired by Random House, which in turn was purchased by media mogul S. I. Newhouse, who inevitably insisted on changes to try to increase profits, unreasonably and unrealistically so, according to Schiffrin: “As one publishing house after another has been taken over by conglomerates, the owners insist that their new book arm bring in the kind of revenue their newspapers, cable television networks, and films do. . . . New targets have therefore been set in the range of 12-15 percent, three to four times what publishing houses have made in the past” (118-19).

Schiffrin documents in detail the mechanisms put in place to try to flog more profits out of the book business, but for our interests perhaps the most fundamental change was the expectation that every title must make a profit, and not just a modest profit. Before the corporate takeover of publishing, it was common practice for publishers to bring out authors’ first books, knowing they would likely lose money and that it may take years and several books before an author found enough of an audience to be profitable. In the meantime, other titles on a publisher’s list could subsidize the nurturing of a new(er) author. A good example is Cormac McCarthy, who is now a household name among readers of contemporary fiction. But McCarthy’s status as an award-winning and best-selling author was a longtime coming. As Daniel Robert King notes in Cormac McCarthy’s Literary Evolution (2016), “Random House took on [in 1965] and retained McCarthy as one of their authors despite unpromising sales over the first twenty years of his career” (23). In fact, McCarthy’s longevity at Random House was due to the loyalty and hardheadedness of his editor Albert Erskine, who insisted that McCarthy’s early titles stay in print in spite of their anemic sales, even in paperback (32-33).

But such loyalty would come to an end when corporations took over the industry, and editors were pitted against each other to reach ever-increasing profit expectations. Decisions about which titles to acquire, how large the print runs should be, and whether or not a contract should be offered for a second book from an author increasingly became the purview of the accounting and marketing departments, and not editorial. By 1990, corporate publishers only wanted to publish books that warranted 100,000 press runs. Anything less wasn’t worth the effort, according to Marty Asher, with the Book-of-the-Month Club and then Vintage (qtd. in Schiffrin 106). Obviously such bottom-line-minded expectations would make it foolhardy for an editor to take on a first book from just about any author, even a Cormac-McCarthy-to-be.

This emphasis on profit also impacted representations of ideology. By and large, corporations are run by conservatives (think Rupert Murdach), so it hasn’t just been new authors who have been silenced but any author writing from a liberal perspective. For a time, this corporate bias toward conservatism was somewhat offset by university and independent publishers, but they, too, have been impacted by changes in the publishing world, either due to acquisitions or universities which have had to be more money-minded to stay afloat. It is worth noting that André Schiffrin’s book on the demise of independent publishing is nearly twenty years old. On nearly every front things have gotten worse since 2000. Today there are essentially five commercial publishers remaining in the United States, according to Publisher’s Weekly, the so-called “Big Five”: Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, Hachette Book Group, and Macmillan (Scholastic is number-six, thanks in large part to their publishing the Harry Potter series) (Milliot). These publishers account for more than eighty percent of sales in the U.S.

All of this has led to a homogenization in publishing. It is fiscally safer to publish book after book by the same few dozen authors (James Patterson, Danielle Steele, Nora Roberts, Dan Brown, etc.) than take a chance on a new voice, or if it is a new author, it’s a new author whose book sounds very much like one that proved successful. The runaway success of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series, for example, gave birth to a new genre: “teen paranormal romance,” essentially beautiful but troubled young women falling in love with vampires, werewolves, ghosts, sea monsters, etc.—Prince Charmings, with fangs, fur, chills or gills.

Meanwhile, along came the Internet. Towards the end of Schiffrin’s book on publishing, again, which came out in 2000, he was mildly optimistic that technological advances could be an avenue for worthwhile books to reach readers. In a sense, his optimism was well-founded. The rise of e-readers and print-on-demand books, in both hardcover and paperback, has made it possible for almost anyone to get their words into print. For example, in 2012 I established Twelve Winters Press, a print-on-demand and digital publisher, to produce my own books as well as other worthy books whose authors were frustrated in finding outlets for their work. We’ve averaged four to six titles per year, mainly fiction, but also poetry and children’s books. Our books are available globally and are reasonably priced. Titles have won awards, and one of our books recently won best cover design in the category of fiction.

We’re only missing one element to be considered a rousing success in independent publishing: readers, also known as book sales. Practically no one will read our books. It is extremely difficult to get our books reviewed—and literally impossible to get them reviewed by major reviewers—and when they are reviewed, reviewers seem duty-bound to moderate their praise with some bit of negative criticism. But it probably wouldn’t matter. Even glowing book reviews have little to no impact on sales. Nearly all of the prestigious book competitions are off limits to small, independent publishers. Either their entry fees are too high, or they require a minimum print run that small presses can’t attain. We’ve had some success in indie competitions, but even they are expensive by small-press standards, and, again, success doesn’t translate to sales. We advertise our books and authors through social media, and for the last couple of years we’ve spent $2,000 to $3,000 annually on traditional advertising, including ads in The New York Review of Books. Practically nada, almost literally nothing. I may as well have shoveled all that cash into an incinerator.

The problem is that a smaller and smaller percentage of Americans are readers, and those who are readers are not interested in well-written, challenging texts. Data on how little Americans read, in every age group, are readily available. What is difficult to discern in the numbers is how little literature is being read. Surveys and studies tend to identify how frequently novels are being read, but it would seem that the vast majority of those books are mysteries, thrillers and other light genres. Perhaps one way of getting some idea of how much literature is being read is to compare it to poetry. According to Statista, eleven percent of Americans claim to read poetry on a regular basis. The reliability of these numbers is suspect, of course, but it may give us some sense of the situation.

One difficulty is answering the question, How does one define literature? William Gass seemed to have a working definition at least, one that he shared in a 1981 interview when he said, “Readers don’t want difficult works—not just mine—anybody’s. The reward for the time, effort, agony of getting into some of these things is always problematic” (Castro 71). Nearly a decade before, Gass compared writing serious fiction to writing poetry, as far as reception was concerned:

I think fiction is going the way of poetry. It’s getting increasingly technical, increasingly aimed at a small audience, and so forth. And this is what happened to poetry—over a long period of time. And now fiction, which I suppose was once a leading popular art form, certainly isn’t any more. And serious fiction does not even hope for it. (Mullinax 14)

If not serious fiction, then, what is being published, especially by the Big Five commercial publishers? According to Gass, in 1976, “[a] lot of modern writers . . . are writing for the fast mind that speeds over the text like those noisy bastards in motor boats. . . . They stand to literature as fast food to food” (LeClair 25). Indeed, in the early 1970s Gass saw the trend developing of a negative correlation between the quality of the writing (the seriousness of it) and its likelihood for being published at all. Regarding his eventual novel The Tunnel, Gass said that if he achieved his goal “perhaps it will be such a good book no one will want to publish it” (McCauley 12). It was published eventually, in 1995, after nearly thirty years of literary labor. By then Gass claimed that he “expected to be ignored. . . . There were some [critics] who were quite enthusiastic, but by and large it was the usual: just shrugs and nobody paid much attention” (Abowitz 145).

In essence, then, our culture—really, Western culture—has lost the literary voice: today’s Joyce, Woolf, Faulkner, Lawrence, Gass, and so on. It’s an uphill struggle to find a publisher, and once found an even steeper struggle to find readers. Who today would publish Ulysses, leave be Finnegans Wake? If published, perhaps self-published, who would read it?

My time for this presentation grows short, so let me shift gears to the issue of What does it matter that less and less literature is being read? For one thing, I see the rise of Trump and Trumpism, which is synonymous with racism, White Nationalism, xenophobia, misogyny, and a host of other evils, as being related to the loss of the literary voice. This topic is clearly complex, and I can only barely begin to introduce it here, but we know that Trump supporters are in the minority in the United States, perhaps thirty to forty percent of the population, and we know that most of those Trump supporters live in non-urban areas—places where the demographic of white, Christian, heterosexual, patriarchal folks reside in insulated enclaves. They are fed their news and their views from conservative outlets and from Trump himself via Twitter, Fox News, Breitbart, etc. Meanwhile, we know that reading increases awareness of others—let’s say capital “O” Others—and study after study has shown that reading about those not like ourselves also fosters empathy.

Interwoven here is the subject of censorship, which I want to touch on briefly. In The Business of Books, Schiffrin discusses how right-leaning conglomerates overlook left-leaning authors, but beyond that editors in dog-eat-dog corporate publishing houses reject material for fear of its unpopularity, which would in turn adversely affect their pay and job security. Another disturbing trend is self-censorship among readers. It seems that the rising tide of conservatism is creating readers who won’t allow themselves to read material they deem immoral. A couple of anecdotes. In January I attended the MLA National Convention in Chicago, and one of the panels I went to was on Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint turning fifty. Two of three Roth scholars were from Midwestern universities, and they said they hadn’t actually taught Portnoy’s for years because their graduate students are too squeamish to discuss the book in class. The third Roth person was a professor at Princeton, and he was nonplussed. Apparently he teaches his Ivy Leaguers Portnoy’s every other semester.

I had a similar experience just last quarter. For our final reading I had assigned William Gass’s novella Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife. I had one grad student refuse to read it when he discovered it contained “raunchy” language. A couple of other students read it but were put off by its language and sexual subject matter. I’ve been thinking that a fascist society hardly needs to bother imprisoning writers and burning books in the square if they can create a culture where most people don’t like to read and even budding “intellectuals” censor themselves on moral or religious grounds.

Speaking of Gass, long before the deleterious effects of the Internet and cable news could be known, he saw the handwriting on the wall. In his commencement address to the Washington University (St. Louis) Class of 1979, Gass cautioned the grads: “We are expected to get on with our life, to pass over it so swiftly we needn’t notice its lack of quality, the mismatch of theory with thing, the gap between program and practice. . . . We’ve grown accustomed to the slum our consciousness has become” (“On Reading to Oneself” 222) The cure Gass advised is the reading of great books, “for reading is reasoning, figuring things out through thoughts, making arrangements out of arrangements until we’ve understood a text so fully it is nothing but feeling and pure response” (227). Elsewhere Gass emphasized that “the removal of bad belief [is] as important to a mind as a cancer’s excision [is] to the body it imperil[s]. To have a head full of nonsense is far worse that having a nose full of flu . . .” (“Retrospection” 51). He went on to recommend rigorous self-skepticism regarding one’s own ideas, “theorizing” about errors in thinking: “Skepticism,” he said, “was my rod, my staff, my exercise, and from fixes, my escape.”

We must make those who are prone to bigotry, who believe brown-skinned migrants deserve to be tossed in cages or left to perish in rivers and at sea, who are anxious to accept any fraudulent information that supports their worldview, who deny the threat of climate change in spite of the data, who believe healthcare is a privilege—we must make them self-skeptical, as Gass advised. We must get them in the habit of questioning their own beliefs. We must get them reading again. Or as Laurie Champion describes it, in her article on Thoreau and Bobbie Ann Mason, we must get people in “a transcendental state of mind that involves intellectual and spiritual searches that lead to clear sight” (57).

Doing that, no matter how difficult, must be our mission.

Note

1 I realize of course that I’m not the first person to lament the sorry state of serious writing in their time. Just a few examples: Emerson, Margaret Fuller and other Transcendentalists founded The Dial in 1840 due in large part to the dearth of decent reading material in spite of their periodical-rich time period. Victorian and Edwardian editor and critic Edward Garnett frequently clashed with the publishers for whom he worked because he felt they didn’t do enough to cultivate a more cosmopolitan appetite among England’s overly conservative and insulated readers. James Joyce famously exiled himself to the Continent mainly due to the sad state of Irish letters. A key difference perhaps, between these thens and now, is that there were a lot of people reading a lot of material, whereas today fewer and fewer people are reading, anything, period.

Works Cited

Abowitz, Richard. “Still Digging: A William Gass Interview.” Ammon, pp. 142-148.

Ammon, Theodore G., editor. Conversations with William H. Gass. UP of Mississippi, 2003.

Castro, Jan Garden. “An Interview with William Gass.” Ammon, pp. 71-80.

Champion, Laurie. “‘I Keep Looking Back to See Where I’ve Been’: Bobbie Ann Mason’s Clear Springs and Henry David Thoreau’s Walden.” Southern Literary Journal, vol. 36, no. 2, 2004, pp. 47-58.

Gass, William H. “The Artist and Society.” Fiction and the Figures of Life, Knopf, 1970, pp. 276-288.

—. “On Reading to Oneself.” Habitations of the Word, Simon & Schuster, 1985, pp. 217-228.

—. Preface. In the Heart of the Heart of the Country, by Gass. 1968. Godine, 1981, pp. xiii-xlvi.

—. “Retrospection.” Life Sentences. Knopf, 2012, pp. 36-55.

King, Daniel Robert. Cormac McCarthy’s Literary Evolution: Editors, Agents, and the Crafting of a Prolific American Author. The U of Tennessee P, 2016.

LeClair, Thomas. “William Gass: The Art of Fiction LXV.” Ammon, pp. 17-38.

McCauley, Carole Spearin. “William H. Gass.” Ammon, pp. 3-12.

Milliot, Jim. “Ranking America’s Largest Publishers.” Publisher’s Weekly, 24 Feb. 2017, https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/72889-ranking-america-s-largest-publishers.html. Accessed 14 April 2019.

Mullinax, Gary. “An Interview with William Gass.” Ammon, pp. 13-16.

Schiffrin, André. The Business of Books. Verso, 2000.

In the Heart of the Heart of Despair

“In the Heart of the Heart of Despair: Seclusion in the Fiction of William H. Gass” was presented at the American Literature Association annual Conference on American Literature in Boston, May 25-28, 2017. It was part of the panel “The American Recluse: Contesting Individualism in Narratives of Isolation and Withdrawal,” chaired by Susan Scheckel, Stony Book University. The panel was organized by Matthew Mosher (Stony Brook), and he presented his paper “‘Our Inviolate Realm’: Self-Reliance and Self-Destruction in E. L. Doctorow’s Homer & Langley.”

First of all, I’d like to thank Matt Mosher for inviting me to join this panel on recluses in American fiction. His invitation encouraged my wife Melissa and me to attend this terrific conference for the first time, and visit Boston for the first time. More important, however, Matt has opened my eyes to an aspect of William H. Gass’s work that is so obvious and so foundational I never quite saw it in spite of spending the last decade of my scholarly life focused primarily on Gass (aka, “the Master”). From his very first fiction publication, the novel excerpt “The Triumph of Israbestis Tott” (from Omensetter’s Luck) in 1958, to his most recent, 2016’s collection of novellas and stories, Eyes, Gass’s protagonists have almost always been solitary souls, withdrawn from their various social spheres: in a word, reclusive. In various papers and reviews of Gass’s work, I have nibbled around the edges of this realization, discussing the loneliness and/or isolation of individual characters—but I’ve never noticed the pattern, a proverbial 800-pound gorilla in the room of Gass scholarship.

As the title suggests, my main focus for this paper will be Gass’s early experimental story “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” (published independently and as the title story of his seminal collection in 1968); it’s important to note, though, that I could have tossed a dart at my William H. Gass bookcase and whichever spine it came to rest in would have provided ample material with which to write this paper. According to the law of probability, I likely would have landed my dart in The Tunnel, and it would have been an especially fruitful stroke of fate. I say it would have been likely because Gass’s American Book Award-winning novel tips the scales at more than 650 pages, and I have three copies (plus the audiobook) among the volumes in my Gass bookcase. I describe the dart’s prick as fruitful because the first-person narrator William Kohler (a sort of William Gass doppelgänger) spends the entire 650 pages of the book sitting alone in his basement writing a highly personal and ego-centric memoir, which is The Tunnel itself.

As the title suggests, my main focus for this paper will be Gass’s early experimental story “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” (published independently and as the title story of his seminal collection in 1968); it’s important to note, though, that I could have tossed a dart at my William H. Gass bookcase and whichever spine it came to rest in would have provided ample material with which to write this paper. According to the law of probability, I likely would have landed my dart in The Tunnel, and it would have been an especially fruitful stroke of fate. I say it would have been likely because Gass’s American Book Award-winning novel tips the scales at more than 650 pages, and I have three copies (plus the audiobook) among the volumes in my Gass bookcase. I describe the dart’s prick as fruitful because the first-person narrator William Kohler (a sort of William Gass doppelgänger) spends the entire 650 pages of the book sitting alone in his basement writing a highly personal and ego-centric memoir, which is The Tunnel itself.

I’ve chosen to focus primarily on Gass’s earlier work, however, because it’s more manageable given the context of this paper, and also it provides ample insights to what I believe is at the core of this phenomenon: this pattern of isolated characters in Gass’s fiction. (As I write this paper, I’m anxious to hear what Matt and my fellow panelists have to say on the subject of reclusive characters and see if it complements or contradicts my ideas about Gass’s characters.) I shall leave you, for the moment at least, in deductive suspense regarding my theory.

Earlier I referred to “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” as an experimental story. “Experimental” is certainly true; for “story” one must broaden one’s sense of the word. A story is normally something with a plot, that is, a discernible conflict and at least a nod toward resolution. Not so with the Master. “In the Heart” features 36 sections with subheadings. The sections vary in length from just a few sentences to several pages, and their styles range from coldly clinical to lusciously lyrical. There is no central conflict, at least not in a typical sense. The story was somewhat inspired by William Yeats’s poem “Sailing to Byzantium” (1927)—in fact, it begins by more or less quoting from the poem’s second stanza, “So I have sailed the seas and come . . . to B . . .” —and its structure is loosely based on the ottava rima form that Yeats used for his 32-line poem. It is their kindredness in theme, though, which is of greatest importance to our purpose here.

Yeats begins by lamenting the deterioration of his physical self due to old age (he was in his sixties when he wrote “Sailing to Byzantium”), but ends with the understanding that the physical is fleeting while the soul that aspires to a higher artistic ideal is immortal. In Gass’s story, the unnamed first-person narrator is an aging poet who has come to B, a small town in Indiana, and is reflecting on his life in this mundane Midwestern locale, season upon season, year upon year. “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” is not merely a prose interpretation of Yeats’s poem, which ends on a more optimistic note than it began. On the contrary, Gass’s story starts bleak and only grows darker. Repeatedly the narrator refers to his own isolation and loneliness, as well as to the isolation and loneliness of his Hoosier neighbors. Early in the story, he tells us that he is “in retirement from love,” and “I’m the sort now in the fool’s position of having love left over which I’d like to lose; what good is it now to me, candy ungiven after Halloween?” (173). The story concludes, 28 pages later, with the narrator’s sense of isolation at Christmastime in the town, a time which represents the pinnacle of the town’s communal life. He finds himself (or merely imagines himself) in the deserted downtown, which has been bedecked for the holiday: “But I am alone, leaning against a pole—no . . . there is no one in sight. […] There’s no one to hear the music [“Joy to the World”] but myself, and though I’m listening, I’m no longer certain. Perhaps the record’s playing something else” (206).

Yeats begins by lamenting the deterioration of his physical self due to old age (he was in his sixties when he wrote “Sailing to Byzantium”), but ends with the understanding that the physical is fleeting while the soul that aspires to a higher artistic ideal is immortal. In Gass’s story, the unnamed first-person narrator is an aging poet who has come to B, a small town in Indiana, and is reflecting on his life in this mundane Midwestern locale, season upon season, year upon year. “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” is not merely a prose interpretation of Yeats’s poem, which ends on a more optimistic note than it began. On the contrary, Gass’s story starts bleak and only grows darker. Repeatedly the narrator refers to his own isolation and loneliness, as well as to the isolation and loneliness of his Hoosier neighbors. Early in the story, he tells us that he is “in retirement from love,” and “I’m the sort now in the fool’s position of having love left over which I’d like to lose; what good is it now to me, candy ungiven after Halloween?” (173). The story concludes, 28 pages later, with the narrator’s sense of isolation at Christmastime in the town, a time which represents the pinnacle of the town’s communal life. He finds himself (or merely imagines himself) in the deserted downtown, which has been bedecked for the holiday: “But I am alone, leaning against a pole—no . . . there is no one in sight. […] There’s no one to hear the music [“Joy to the World”] but myself, and though I’m listening, I’m no longer certain. Perhaps the record’s playing something else” (206).

Meanwhile, in the heart of the story, the narrator describes, here and there, his various fellow townspeople, especially his neighbor Billy Holsclaw, who “lives alone” (179). The narrator paints a sad picture of Billy (unshaven, dirty with “coal dust,” dressed in “tatters”), and ends the initial section about him with the statement “Billy closes his door and carries coal or wood to his fire and closes his eyes, and there’s simply no way of knowing how lonely and empty he is or whether he’s as vacant and barren and loveless as the rest of us are—here in the heart of the country” (180). We note that the narrator describes Billy’s actions inside of his house even though it is not possible for him to know what goes on after Billy shuts the door; thus, the narrator seems to be assuming Billy’s behavior based on his own, alone in his own house. This point brings up an important issue in the story: How does the narrator have access to all that he describes in B? H. L. Hix asserts, “He does not wander out into the world, so the reader gets not a picture of B, but a picture of the narrator’s confinement, the view from his cell” (49). Not literal cell of course: the cell of his isolation, his loneliness: the cell from which he projects everyone else’s isolation and loneliness.

Referring to the narrator’s view underscores what would become a major motif in Gass’s fiction: the window. There are numerous references to windows and what the narrator sees framed in them in “In the Heart.” He describes the windows of his house as “bewitching [. . . with] holy magical insides” (179). Through his window he views vivacious young women and fantasizes about them: “I dreamed my lips would drift down your back like a skiff on a river. I’d follow a vein with the point of my finger, hold your bare feet in my naked hands” (179), and “[Y]our buttocks are my pillow; we are adrift on a raft; your back is our river” (188). However, he knows he is well beyond the point when any such contact could reasonably take place. This realization makes especially poignant his later observation that rather than interacting with the world directly he has “had intercourse by eye” (202). That is, he has lived mainly through observation of his fellow human beings, not by talking to and connecting with them directly.

As I said, references to windows are everywhere in Gass’s oeuvre. The story “Icicles,” also collected in In the Heart of the Heart of the Country, begins with the main character, Fender, sitting down to a lonely dinner eaten from a tray in his living room and looking through his picture window: “[H]is gaze pass[es] idly along the streets in the wheel ruts and leaping the disorderly heaps of snow. He was vaguely aware of the ice that had curtained a quarter of his window . . .” (121). Here the ice emphasizes the coldness of this sort of existence, an existence void of human warmth for Fender, even though his profession as a real estate agent requires him to interact with people all the time. Unlike the narrator of “In the Heart,” Fender does engage with people, but this engagement does not lessen his isolation; it only amplifies it. This is an important variation on the theme of isolation in Gass’s work. Often, Gass’s characters are not literally alone, but they feel isolated and lonely nevertheless. William Kohler in The Tunnel is married, but to a wife he hates and who has no interest in his life’s work as a historian. As the title suggests, Babs, the wife in the novella Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife, is isolated, lonely and horny in spite of her marital status, or perhaps because of it. The ironically named, antisocial Mr. Gab of the novella “In Camera” spends his dreary days inside his shop that sells black-and-white photographic prints, with only his assistant Stu (short for “stupid”) for company. The boy-narrator, Jorge, in “The Pedersen Kid” is living among his family on a farm in North Dakota but is as desperately lonely as a boy can be thanks to his bellicosely alcoholic father, brutalized and traumatized mother, and live-in farmhand Hans, who may be molesting Jorge. The list goes on and on. (The Master is a real feel-good kind of author.)

All fictive writing is autobiographical to some degree, but Gass has never been one to make the veil especially opaque. The autobiographical elements flash neon in his work, and in his copious interviews he has been happy to connect the dots for readers and critics. In The Tunnel (his magnum opus) and Willie Masters’ he’s given the main characters his own name, or variations of it. The tunnel-digging William Kohler is a university professor, as was Gass, with a history and a list of interests quite similar to Gass’s. Eerily similar; disturbingly similar for some readers. Joseph Skizzen of the novel Middle C is an isolated music professor who specializes in Arnold Schoenberg, the composer whose twelve-tone system Gass used to structure The Tunnel. Like Jorge in “The Pedersen Kid,” Gass was born in North Dakota and grew up an only child in a family devastated by alcoholism and hatred. The list goes on and on.

Understanding the extremely close—at times, uncomfortably close—connection between Gass himself and his characters is especially important when viewed alongside his fascination with windows. Hix explains: “The window, which represents the ambiguity of our connection to the world, our looking out on a world from which the very looking out separates us, has appeared as a metaphor regularly in Gass’s […] fiction” (124). Windows, then, and their representation of separation through observation, seem to be a commentary on Gass’s own sense of isolation: that is, Gass the writer, Gass the intellectual, Gass the artist. It is the artist’s job—their curse perhaps—to observe the world around them, closely; to think about it, deeply; and share their interpretations with the world, honestly. It is a vital function, but one that requires and creates distance from one’s family, friends, colleagues, and neighbors. In a 1984 interview, Gass identified himself as “a radical, but not one allied with any party. Parties force you to give up your intellect” (Saltzman 92). In other words, he was, in essence, a lone-wolf radical. To clarify, Gass has not seen himself as a writer with an overt political agenda, but rather one with a loftier, more ethereal, more profound goal: the alteration of his readers’ consciousness. [About the photo: William H. Gass painted by Philip Guston for his lecture at Yaddo, “Why Windows Are Important To Me,” 1969.]

In his landmark essay “The Artist and Society” (1968), Gass writes that the artist is “[naturally] the enemy of the state” and “[h]e is also the enemy of every ordinary revolution” (287). Moreover, he “cannot play politics, succumb to slogans and other simplifications, worship heroes, ally himself with any party, suck on some politician’s program like a sweet. […] He undermines everything.” Again, the artist/writer as lone-wolf radical. The payoff, though, can be sublimely effective. Gass writes, “The artist’s revolutionary activity is of a different kind. He is concerned with consciousness, and he makes his changes there. His inactions are only a blind, for his books and buildings go off under everything—not once but a thousand times. How often has Homer remade men’s minds?” (288). In other words, to be the sort of artist, the sort of writer, the sort of radical Gass admires most—the sort whose work will be worth reading a century from now, or a millennia—he must be solitary and isolated: the observer behind the window encased in ice.

If this paper were to be extended, I’d try to make the case that Gass’s philosophy may be traceable to one of his idols, the French writer Paul Valéry, of whom he said, “He dared to write on his subjects as if the world had been silent . . .” (Fiction and the Figures of Life, xi). Known mainly as a poet and essayist, Valéry also wrote the novella “The Evening with Monsieur Teste” (1896), whose title character is an isolated intellectual very much akin to many of Gass’s fictional creations, especially William Kohler and Joseph Skizzen. In the Preface to his novella, Valéry describes the philosophy which led to the creation of the character Monsieur Teste (or, in English, essentially “Mr. Head”), and I think at this point we can see that it could have been written by his devotee, William H. Gass. I shall let Valéry’s translated words be my final ones here:

If this paper were to be extended, I’d try to make the case that Gass’s philosophy may be traceable to one of his idols, the French writer Paul Valéry, of whom he said, “He dared to write on his subjects as if the world had been silent . . .” (Fiction and the Figures of Life, xi). Known mainly as a poet and essayist, Valéry also wrote the novella “The Evening with Monsieur Teste” (1896), whose title character is an isolated intellectual very much akin to many of Gass’s fictional creations, especially William Kohler and Joseph Skizzen. In the Preface to his novella, Valéry describes the philosophy which led to the creation of the character Monsieur Teste (or, in English, essentially “Mr. Head”), and I think at this point we can see that it could have been written by his devotee, William H. Gass. I shall let Valéry’s translated words be my final ones here:

I made it my rule secretly to consider as void or contemptible all opinions and habits of mind that arise from living together and from our external relations with other men, which vanish when we decide to be alone. And I could think only with disgust of all the ideas and all the feelings developed or aroused in man by his fears and his ills, his hopes and his terrors, and not freely by his direct observation of things and himself. . . . I had made for myself an inner island and spent my time reconnoitering and fortifying it. . . . (4-5)

Works Cited

Gass, William H. “The Artist and Society.” Fiction and the Figures of Life, Godine, 1979, pp. 276-88. [The complete draft, from William H. Gass’s papers, is available online via Washington University.]

—. “Icicles.” In the Heart of the Heart of the Country and Other Stories, Godine, 1981, pp. 120-162.

—. “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country.” In the Heart of the Heart of the Country and Other Stories, Godine, 1981, pp. 172-206.

—. Preface. Fiction and the Figures of Life, Godine, 1979, pp. xi-xiii.

Saltzman, Arthur M. “An Interview with William Gass.” Conversations with William H. Gass, edited by Theodore G. Ammon, UP of Mississippi, 2003, pp. 81-95.

Valéry, Paul. Monsieur Teste. Translated by Jackson Mathew, Princeton UP, 1989.

Interview with Theo Landsverk: The Madman’s Rhyme

Shining Hall, an imprint of Twelve Winters Press, has recently released the book of children’s poetry, The Madman’s Rhyme, written and illustrated by Theo Landsverk. All of my press’s releases are special, but this one is especially so because The Madman’s Rhyme began as a class project by one of my students, and I approached Theo about transforming the project into a publishable book. He was interested, but we had to wait for him to be old enough to sign the publishing agreement. Also, the manuscript wasn’t quite long enough to be a book, so he took some time to add more material, and also to tidy up some of the illustrations via Photoshop.

Everything came together by end of 2015, so we went to work on producing the book, which was released in hardcover and Kindle editions in February. It’s become a tradition for me to interview the press’s authors when their work is released, so I sent Theo some questions and what follows are his responses.

How would you describe the process you used to create “The Madman’s Rhyme”? Did the poetry tend to come first, and then you illustrated the poems? Or did the art come first and the words followed?

I would describe the process to be like the growth of a plant. First comes the seed, an idea. Then roots come next, which would be a line of poetry. More lines of poetry trickle after each other until a stem of poetry is produced. Once the poem was completely grown the illustrations would blossom around it.

Which did you find more challenging, writing the poems or creating the artwork? Why?

I found both of them to have their challenges, but by far the poetry itself was the toughest part. Fragments of poetry would pop in my head without trying but the hard part was completing the poem. Some days I had more poetic creativity and inspiration than others so that also caused some trouble when I was on a deadline.

The Madman’s Rhyme is considered children’s literature; however, some may consider the themes of some of the poems as being more adult. What are your thoughts on the “appropriate age” of your book?

It is hard to judge a true “appropriate age” for poetry because any age group can enjoy it thoroughly. I myself can enjoy a Dr.Seuss at the age of 18, so if the concern is that older audiences may feel too aged for such childish literature I would say that is nothing to worry about. A lot of my poems tend to have insight on deeper things and darker subjects making some question if this book is suitable for younger children. I can’t really judge that myself because at the age of 8 I was reading Poe’s poetry and stories. To say it shortly, age is irrelevant when reading poetry.

I have compared your work to the Brothers Grimm and even Edgar Allan Poe. Do those comparisons work for you? Did you read the Grimms as well as Poe growing up?

I feel rather honored to be compared to those works because those are what I indeed read growing up. When I was young I was very fond of fairytales and Disney movies, but I was more in love with the rustic and crude Brothers Grimm stories. They were like the unedited Disney for me. I also read a lot of Poe’s works. I admit it was a lot for an 8-year-old to even try to comprehend deeply, but I still enjoyed it and kept reading his works. It was Poe who inspired me to write poems to begin with.

Did you enjoy reading children’s books of poetry when you were very young? What were some of your favorite children’s books or children’s authors?

I loved reading children’s poetry books growing up. Shel Silverstein’s books had me in awe and held my attention span for so long with his witty words and pen illustrations. I would say his works are right in line with Poe’s when it comes to those who inspired me the most. I also really enjoyed Dr. Seuss, but who didn’t?

I know you’re interested in animation. What do you find so attractive about animation compared to “still” art? What are you goals as far as being an animator?

Animation is visual storytelling. It is bringing life to artwork. The possibilities are endless with animation and those are the reasons it fascinates me. My goal in animation is to work for a big-name company and make children’s movies.

Are there any poems or pictures in The Madman’s Rhyme that you’re especially proud of? Why?

It is really hard to choose because I am proud of them all, but I must say my favorite poems are “Feed Me,””Sip the Sorrow,” and “Wallpaper.” I am not too sure the reason why but those are the ones I treasure most. When it comes to illustrations, those for “Wallpaper,””In the Trenches,” and “Feed Me” are my favorites.

You did some of the illustrations free hand, and for others you used Photoshop . Do you prefer one approach to the other?

I prefer traditional. It feels more personal and almost mystical to illustrate traditionally. The physical process is more rewarding to me and the product is visually unique.

This is your first book, but you’ve won other awards and accolades – for example?

I have won numerous awards in the regional Scholastic Art competitions and New Berlin art competition throughout my high school career. I have also won a poster competition for drug and alcohol abuse awareness.

Do you have some other projects you’re working on, or what are your plans for school, etc.?

As of right now I do not have any major projects I am working on, just small ones to experiment with mediums. My plan for school is to go to the DAVE School (Digital Animation and Visual Effects school) in Florida.

Theo Landsverk reads from The Madman’s Rhyme at the Hoogland Center for the Arts in Springfield, Illinois, March 17, 2016.

The Pharmacy has quickly become a site of literary energy

The Pharmacy art studio, located at the corner of Pasfield and South Grand in Springfield, Illinois, has quickly established itself as not only a site of visual artistic energy but literary artistic energy as well. In addition to hosting readings, often in conjunction with University of Illinois at Springfield’s creative writing program — in recent months poets Stephen Frech and E. E. Smith, and UIS’s undergraduate and graduate creative writers — The Pharmacy has hosted and/or organized writing workshops and open-mic events. Spearheaded by Andrew Woolbright and Adam Nicholson, The Pharmacy Literati have already had a profound impact on promoting and producing literature in Springfield. And all this, of course, is in addition to The Pharmacy’s primary mission to promote visual artists.

Most recently, The Pharmacy hosted novelist (among many other things) A. D. Carson, who read from his novel Cold. I’ve italicized “read” because it was really more of a performance than a simple reading, including wrap, slam poetry, and often accompanied by recorded musical tracks, composed and in large part performed by A. D. In fact, Cold has companion CDs and MP3s (see A. D.’s Amazon page). A. D.’s multifaceted reading was emblematic of The Pharmacy itself in that it’s a creative space which places no boundaries on imagination, regardless of form or content. Art, some completed, some in progress, adorns the walls and various nooks; here, there and everywhere are the various implements and supplies for making art, plus manual and power tools, food stuff, a hodgepodge of furniture, and, of course, books, books, books … on shelves, on tables, on couches. In addition to the artwork, the walls are also home to graffitied quotes.

In sum, The Pharmacy is wonderfully, beautifully messy — it’s sort of like the bedroom of a hypercreative teenager. In other words, it’s like the mind, both conscious and unconscious, of the true artist — whether an artist of images, of words, of sounds: they all come to The Pharmacy to play, and incredible things happen. If you’re creative and/or crave the fruits of creativity, you have to find The Pharmacy in Springfield. (I suspect the name “The Pharmacy” was chosen largely because the old building was indeed a pharmacy, but the founders chose wisely in that it has once again become a place of healing [spiritual and soulful], and the name further suggests the mind-opening and mind-altering effects of certain kinds of pharmacology [some legal, some not].)

I mentioned the readings done by UIS’s student creative writers, and I should add that they were quite good and made for a most enjoyable evening, especially when combined with macaroni and cheese lovingly prepared by the students’ teacher, Meagan Cass. Meagan recently received the good — and much-deserved — news that her story “Girlhunt, Spring 1999” was nominated by Devil’s Lake for a Pushcart Prize. Treat yourself right, and take a few minutes to read “Girlhunt, Spring 1999.”

On my own writing front, since completing the manuscript of my novel “An Untimely Frost” back in June, I’ve been writing a series of loosely connected short stories (four thus far), and one, “Primitive Scent,” was picked up by The Tulane Review, while another, “Crowsong for the Stricken,” was accepted for presentation at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture Since 1900 this coming February. I’ll also be presenting a paper on William H. Gass’s novel The Tunnel at the conference as part of the PsyArt panel. In other news, my publisher, Punkin House, has added Barnes & Noble to its sellers, along with Amazon, and as such a Nook version of Men of Winter is now available. Punkin House’s CEO Amy Ferrell has also informed me that an audio-book edition is in the works.

Meanwhile, the article I was invited to write for Glimmer Train Press’s Writers Ask series has come out in #54: “Researching the Rhythms of Voice.” I wrote about using the collected letters of Washington Irving to assist in capturing the narrative voice I wanted for “An Untimely Frost,” whose first-person protagonist is Washington Irving-esque. Also, the interview with me that Beth Gilstrap wrote for The Fourth River has come out, thanks in no small part to the journal’s fiction editor Robert Yune. Beth talked to me about both Men of Winter and Weeping with an Ancient God, a novella that Punkin House will bring out in 2012, paired with a collection of twelve previously published stories.

I’m at work on a fifth short story, though not of the same fictional ilk as the previous four, but I also need to get my Gass paper shipshape for the Louisville conference. Once those two projects are completed, I’ll turn my writing attention in full to the next novel I have in mind, a work that will be connected with “Primitive Scent” and “Crowsong for the Stricken.” So many tales to tell, so little time … but hopefully enough.

Pathfinding: a blog devoted to helping new writers find outlets for their work

leave a comment