Preface to ‘The Artist Spoke’

Like all novels, The Artist Spoke is about many things — some that I, as the author, am privy to, and some, as the author, I am not. One of the things it’s about (I know) is what it means to be a writer when the book, as an art form, is gasping its final breaths. Why labor over a novel, a story, a poem, an essay when you’re certain almost no one is going to read it?

It’s a question I’ve been contemplating, on various levels, for a number of years — as a writer certainly, but also as a publisher, a teacher, a librarian, and a reader. I have found solace in the words of my literary idol William H. Gass: “Whatever work [the contemporary American writer] does must proceed from a reckless inner need. The world does not beckon, nor does it greatly reward. . . . Serious writing must nowadays be written for the sake of the art.”

Gass shows up, explicitly, a couple of times in The Artist Spoke. I use most of the above quote as an epigraph for Part II of the novel, “Americana.” Then later, the two main characters, Chris Krafft and Beth Winterberry, visit a bookstore where they briefly discuss Gass’s iconic essay collection Fiction and the Figures of Life and specifically its concluding piece “The Artist and Society.” I read the essay often, as a reminder — a kind of mantra — that what I do, answering the call of the “reckless inner need,” is not only worthwhile but important.

Quoting the Master again: “[The world] does not want its artists, after all. It especially does not want the virtues which artists must employ in the act of their work lifted out of prose and paint and plaster into life.” Gass goes on to discuss these virtues, which include honesty, presence, unity, awareness, sensuality, and totality (that is, “an accurate and profound assessment of the proportion and value of things”).

Gass concludes the essay, written toward the end of the 1960s (the Vietnam era), by saying that “the artist is an enemy of the state [. . . but also] an enemy of every ordinary revolution [. . . because] he undermines everything.” That is, to be true to their art, artists must be ready to stand alone. As soon as they lend their voice to a cause, their art becomes something else, like propaganda, jingoism, a corporate slogan.

The Artist Spoke is a departure for me in several ways. For one, it has a contemporary setting. When I began writing the novel, in late 2015 or early 2016, I even intended for it to have a somewhat futuristic setting — but when it takes five years to write a novel nowadays, the future quickly becomes the now, if not the past. My other novels and novellas have been set in the past: Men of Winter (early twentieth century, First World War-ish), Figures in Blue (also early twentieth century), Weeping with an Ancient God (July 1842), An Untimely Frost (1830s), Crowsong for the Stricken (1950s, mainly), and Mrs Saville (1816 or 17).

I prefer writing in a past setting. My current project is set in 1907 (the first three episodes are going to be published by Wordrunner as an e-novella or abbreviated collection, First Kings and Other Stories). I like the definitiveness of the past, and I enjoy reading history — so doing research is one of the most pleasurable parts of the writing process. What rifle would the hunter have been using? When did electricity come to that part of the country? How were corpses embalmed?

Though a devout atheist, I’m fascinated with the Bible, as a narrative and as a cultural artifact, so I often incorporate biblical elements into my fiction. I did this to some degree in Crowsong for the Stricken, but in the current project all the stories (episodes?) are rooted in Bible stories and biblical imagery, which is reflected in their titles: “First Kings,” “Hosea,” “The Widow’s Son,” and (the newest) “The Buzite.”

Religious faith is explored in The Artist Spoke as well. For instance, the novel asks, is faith in literature — or devotion to a particular author — not a kind of religion, and one that could be more meaningful than a traditional religion? A faith’s liturgy, after all, is at the core of its beliefs (in theory). Are not Joyceans, then, a kind of congregation? People who consider life’s meaning through the lenses of Ulysses or Finnegans Wake or another Joyce text, like “The Dead”?

For me, though a fan and admirer of Joyce, my religion is rooted in the writings of William H. Gass. They help me to understand the world and to sort through my own opinions and feelings regarding what the world offers up to me, like a pandemic, like a country where many of its citizens refuse to take precautions against spreading the virus, believing it to be some sort of hoax or conspiracy. Gass said, “One of the themes of my work is that people certainly do not want to know the truth, and they construct all sorts of idiocies to avoid facing it.” Amen.

Reading Gass helps me to cope with what is going on in the country right now. I would want that sort of solace for anyone, for everyone — but one needs to read literature and read it well and read it often. And those days are quickly coming to an end.

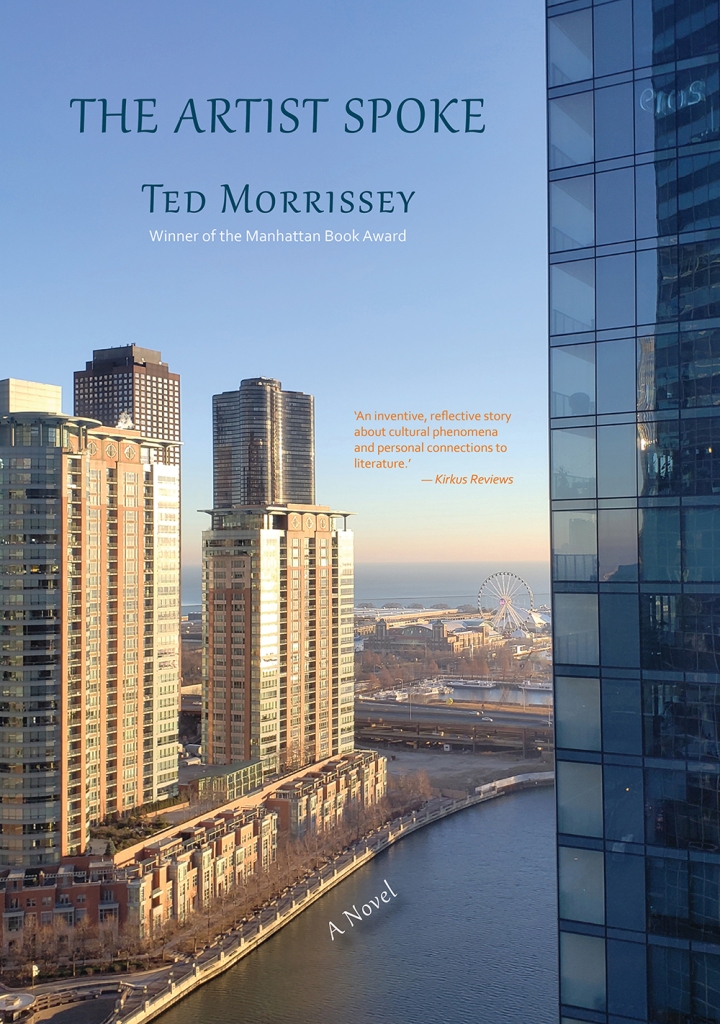

Another way that The Artist Spoke is a departure for me is that I feel I have stepped from behind a curtain to acknowledge that the book is all me: I wrote it, I took the photographs, I designed the book, I designed the cover, I edited it. I have done everything. I have been slowly inching my way into full view. With my last book, Mrs Saville, I was essentially out but was perhaps not quite as vocal about it.

Self-publishing is still seen by many as “vanity publishing.” In other artistic fields, taking charge of your own art is viewed as rebellious and bold: musicians who create their own labels, fashion designers who found their own boutiques, visual artists who start their own galleries, etc. The simple truth is that commercial publishing houses are not interested in what I’m doing in my writing, thus literary agents aren’t either. Nevertheless, I still feel that “reckless inner need”; and, what is more, I enjoy the entire process. I love writing the stories and novels, and I enjoy designing the books and illustrating them.

By taking control of the whole process, I can shape the book into a unified artistic expression. The design can complement the words. I’ve had run-ins over the years with editors, and I’ve been disappointed by the efforts of graphic designers who didn’t seem to get my work (perhaps they didn’t read it, or comprehend it).

That said, I do have an ego, so I seek publication for pieces of my books as I work on them (perhaps I am more sensitive to the charge of vanity publishing than I like to let on). Most of The Artist Spoke appeared in print, here and there, prior to the novel’s full publication, in Floyd County Moonshine, Lakeview Journal, Adelaide Magazine, Central American Literary Review, and Litbreak Magazine. I say in the Acknowledgments, “I wrote this book in fits and starts, often losing my way, at one point abandoning it for nearly two years. The editors who saw something of value in the work and published pieces of it over time provided more encouragement than they can know.”

My ego also hopes at least a few people read and enjoy The Artist Spoke, but I didn’t write it for a mass audience. Ultimately, I suppose, I wrote it for an audience of one. In any case, I give it to the world, to take or to leave. Gass-speed, little book.

William H. Gass’s Transformative Translations of Rilke

The following paper, “The ‘Movement of Matter in Mind’: William H. Gass’s Transformative Translations of Rilke,” was presented at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture Since 1900, held Feb. 20-23, 2020, University of Louisville. Other papers in the panel “Germanic Modernisms Then and Now” were “Exodus into Death: Effi Briest as the Other” by Olivia G. Gabor-Peirce, Western Michigan University; “The Meaning of Life–Thoughts on Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Die Frau ohne Schatten” by Enno Lohmeyer, Case Western Reserve University; and “The Ek-static Image: Tracing Essence of Language & Poetry in Heidegger” by Ariana Nadia Nash, University of Buffalo, SUNY. The panel was chaired by Brit Thompson, University of Louisville.

The “Movement of Matter in Mind”:

William H. Gass’s Transformative Translations of Rilke

I would like to say a motivation for this paper is that one of William H. Gass’s least read and least appreciated books is Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation, and I want to direct some much-deserved attention to this oddly beautiful and beautifully odd book; but in truth I don’t believe I grasped the breadth of the slight until I was absorbing material in preparation of writing. Of course, as a devotee of the Master I believe that all of Gass’s books are read too little and appreciated too sparingly. Indeed I’ve been on a mission for more than a decade to right that wrong.

Nevertheless, I didn’t realize just how invisible Reading Rilke was even among those cherished few who cherish Gass nearly as much as I. I was struck, for example, when re-reading Stanley Fogel’s otherwise excellent assessment of Gass’s work up to the point of its publication in the summer 2005 edition of The Review of Contemporary Fiction that Fogel doesn’t speak of Reading Rilke at all, even though it came out in 1999, and Gass’s translations of Rilke that it collects began to appear in print in 1975 (in North Country, University of North Dakota).1 Similarly, H. L. Hix’s useful Understanding William H. Gass (2002) is organized by Gass’s book publications, and there is no chapter devoted to Reading Rilke. In fact, there is barely a mention beyond Hix’s pointing out the strangeness of the Rilke book not appearing until 1999 even though “Gass reports having been preoccupied with Rilke nearly his whole adult life, indeed seldom letting a day pass without reading some Rilke” (4). One more example: Wilson L. Holloway’s fascinating book William Gass, which offers a mid-career assessment of “an emerging figure in contemporary literature” (ix), makes only a passing reference to Rilke as one of Gass’s chief influences. Granted, Holloway’s book appeared nearly a decade before Reading Rilke, but it also appeared five years before The Tunnel, and yet Holloway managed an entire chapter on the work-in-progress based on the excerpts that had been appearing now and again since 1969—interspersed with appearances of Gass’s Rilke translations throughout the same period.

Nevertheless, I didn’t realize just how invisible Reading Rilke was even among those cherished few who cherish Gass nearly as much as I. I was struck, for example, when re-reading Stanley Fogel’s otherwise excellent assessment of Gass’s work up to the point of its publication in the summer 2005 edition of The Review of Contemporary Fiction that Fogel doesn’t speak of Reading Rilke at all, even though it came out in 1999, and Gass’s translations of Rilke that it collects began to appear in print in 1975 (in North Country, University of North Dakota).1 Similarly, H. L. Hix’s useful Understanding William H. Gass (2002) is organized by Gass’s book publications, and there is no chapter devoted to Reading Rilke. In fact, there is barely a mention beyond Hix’s pointing out the strangeness of the Rilke book not appearing until 1999 even though “Gass reports having been preoccupied with Rilke nearly his whole adult life, indeed seldom letting a day pass without reading some Rilke” (4). One more example: Wilson L. Holloway’s fascinating book William Gass, which offers a mid-career assessment of “an emerging figure in contemporary literature” (ix), makes only a passing reference to Rilke as one of Gass’s chief influences. Granted, Holloway’s book appeared nearly a decade before Reading Rilke, but it also appeared five years before The Tunnel, and yet Holloway managed an entire chapter on the work-in-progress based on the excerpts that had been appearing now and again since 1969—interspersed with appearances of Gass’s Rilke translations throughout the same period.

It seems strange to me, now, that books and articles devoted to explicating William Gass wouldn’t spend more time discussing Gass’s self-identified greatest influence.

I could go on referencing the lack of references in Gass scholarship to Reading Rilke, but, I suspect, my point is beyond made, like a bed piled high with a scaffolding of pillows. I think at the root of the silence regarding Reading Rilke is that writers tend to organize their assessments by genre (Gass’s fiction versus Gass’s criticism or Gass’s nonfiction), and Reading Rilke is a hodgepodge of a book: part Rilke biography, part autobiography, part criticism, part philosophical inquiry (into translation, into art), and part poetry collection—laced throughout with Gass’s insights, advice, and arid humor. Writers of Gass’s ilk have always written for a narrow audience (an audience which shrinks by the day), and the book’s various components appeal to even thinner subgroups of readers. Taken as a whole, however, I believe anyone who is interested in art, literature, and especially poetry—in aesthetics in other words—would find a book very much to taste, indeed, a book to savor.

I could go on referencing the lack of references in Gass scholarship to Reading Rilke, but, I suspect, my point is beyond made, like a bed piled high with a scaffolding of pillows. I think at the root of the silence regarding Reading Rilke is that writers tend to organize their assessments by genre (Gass’s fiction versus Gass’s criticism or Gass’s nonfiction), and Reading Rilke is a hodgepodge of a book: part Rilke biography, part autobiography, part criticism, part philosophical inquiry (into translation, into art), and part poetry collection—laced throughout with Gass’s insights, advice, and arid humor. Writers of Gass’s ilk have always written for a narrow audience (an audience which shrinks by the day), and the book’s various components appeal to even thinner subgroups of readers. Taken as a whole, however, I believe anyone who is interested in art, literature, and especially poetry—in aesthetics in other words—would find a book very much to taste, indeed, a book to savor.

I must admit that I came to Reading Rilke after partaking of the Master’s less hybridized offerings. Like many, I found the fiction first (In the Heart of the Heart of the Country, for instance, and Omensetter’s Luck); then the criticism (Fiction and the Figures of Life, On Being Blue, and The World Within the Word, etc.). But anyone who knows Gass at all knows of his Rilke obsession, something about which he made no bones.

It is clear in Gass’s “Fifty Literary Pillars,” in which he catalogs the (actually) fifty-one books/authors that shaped him as a writer and thinker. Four of the pillars belong to Rilke, and about the Duino Elegies in particular Gass writes, “[These poems] gave me my innermost thoughts, and then they gave those thoughts an expression I could never have imagined possible.” While discussing Sonnets to Orpheus, Gass acknowledges that “[i]t is probably embarrassingly clear by now that works of art are my objects of worship,” and, moreover, “works of art are often more real than we are because they embody human consciousness completely fulfilled” (WHG Reader 43). Heide Ziegler, a scholar and a friend of William Gass with whom he consulted on his Rilke work, describes the Gass-Rilke connection even more dramatically than Gass did himself, writing, “William H. Gass is Rainer Maria Rilke’s alter ego, deeply tied to him through like sensitivity, insight, giftedness. Deeply tied to him most of all, however, through their shared concept of space, Rilke’s Raum, Weltraum, the realm of all things, which denies any chronological sequence” (55). She goes further in describing their connectedness: “Gass the son attempts to provide that space for Rilke the father” (56).

We do not, of course, have to rely on secondary-source assessments of what Rilke meant to Gass and his work: we have Gass’s own analyses, especially in Reading Rilke:

The poet himself is as close to me as any human being has ever been […] because his work has taught me what real art ought to be; how it can matter to a life through its lifetime; how commitment can course like blood through the body of your words until the writing stirs, rises, opens its eyes; and, finally, because his work allows me to measure what we call achievement: how tall his is, how small mine. (xv-xvi)

Regarding the creative process as he learned it from reading Rilke, Gass writes, “In the case of the poet, the perception will have soaked for a long time in a marinade of mind, in a slather of language, in a history of poetic practice.” At which point the “resulting object will not be like other objects; it will have been invested with consciousness, the consciousness of the artist.” Done properly, those who experience the object “shall share this other superior awareness” (148). It is worth noting that Gass is using poet in a classical sense, as anyone who aspires to create art. Though Gass did not consider himself a poet per se (and in fact disparaged his own efforts), he aspired to make his fiction, especially, art objects via their poetic use of language.

The above quote references the word perception, and this is such a vital point in this discussion it warrants further attention. Gass believed that Rilke’s aesthetic philosophy grew out of his infatuation with the sculptor Rodin, about whom he wrote critical essays and was attached to as a secretary for a time. The lessons learned included that “the poet’s eye needs to be so candid that [… everything] must be fearlessly reported,” and that “exactitude is prerequisite to achievement.” Ultimately, then, it is “not the imitation of nature but its transformation [that] is the artist’s aim” (Reading Rilke 40). However, it is not the poet’s objective to describe everything encountered with candor and precision. Art only happens via careful selection. Gass writes, “Rilke proclaimed the poet’s saintly need to accept reality in all its aspects, meanwhile welcoming only those parts of the world for which he could compose an ennobling description” (31). The only means by which a poet—any writer—has to ennoble even the ugliest aspects of the world is though the artful use of language.

This lesson is perhaps the most profound one that Gass took from his literary idol. Throughout his career, Gass mixed the loveliest of language with the coarsest (even crudest) of subject matter, a technique that many critics criticized. Indeed, in Gass’s most ambitious novel, The Tunnel, his greatest ambition was to write about the Holocaust in a beautifully literary way via his first-person narrator William Kohler, whose correspondences with Gass himself were uncomfortably close for many readers. After a twenty-six-year gestation, The Tunnel appeared in 1995 and promptly won the American Book Award in ’96; however, it also quaked a tidal wave of negative reviews. Richard Abowitz, who interviewed Gass about his book in 1998, captured the controversy quite succinctly:

The Tunnel may well be the greatest prose performance since Nabokov’s Pale Fire, but only the most stalwart reader will be able to last the full trip [650-plus pages] through Kohler’s anti-Semitic, sexually depraved and bathroom-humor obsessed world. When The Tunnel was published, almost every major critic felt the need to weigh in on it. Many abandoned their professional tone and responded in ways that were shockingly personal. (142)

Gass claimed that he was prepared for the onslaught, saying, “I knew it would happen. The book does set a number of traps for reviewers, and that identification certainly occurred [that Gass and his narrator were practically the same person]. But the book in sly ways even encourages it; so that these people who don’t really know how to read will fall into the trap.” He added, “[S]o when it happened, I had to suffer it. I had asked for it in a way” (144).

Returning to Reading Rilke itself, the opening chapter is a biographical sketch of the poet. In “Fifty Literary Pillars,” Gass calls Rilke “the most romantic of romantics” (WHG Reader 43), and in this first chapter Gass explains in detail this designation. He writes, “With a romantic naiveté for which we may feel some nostalgia now, and out of a precocity for personality as well as verse, Rilke struggled his entire life to be a poet—not a pure poet, but purely a poet—because he felt, against good advice and much experience to the contrary, that poetry could only be written by one who was already a poet: and a poet was above ordinary life” (23). Gass devotes several sentences to describing the concept of a true poet, and concludes by saying that “the true poet was an agent of transfiguration whose sole function was the almost magical movement of matter into mind” (24).

Gass’s reputation as a literary critic was at least equal to his reputation as a writer of fiction. Indeed, among the things that impeded the production of his fiction, which he preferred to write, were the unending requests to write reviews and to speak at symposia—requests that were accompanied by a paycheck and were therefore difficult to turn down. One of the joys of reading Reading Rilke is that Gass has collected and expanded on his insights into the act of literary translation, which, he says, is the highest form of reading: “Translating is reading, reading of the best, the most essential kind” (50). That is, to render something, like a poem, into your mother tongue from a language that you have learned through study, you must read carefully, deeply and slowly, meanwhile taking into consideration a plethora of contextual elements. Even still, the most successful of translations leave behind something important in the original: “It is frequently said that translation is a form of betrayal: it is a traduction, a reconstitution made of sacrifice and revision. One bails to keep the boat afloat” (51).

Gass elaborates on the idea of translation as essential reading by comparing his translations of specific Rilkean lines to those produced by other translators, organized chronologically from Leishman (1939) to Oswald (1992), and then Gass himself in 1999: fifteen translators of Rilke all together. Gass carefully critiques each rendering, discussing the choices each translator made, what they captured of the original and what escaped. His critiques are ruthless, but he is just as hard on himself. He refers to himself in the third-person as “a jackal who comes along after the kill to nose over the uneaten hunks, keeping everything he likes” to acknowledge his debt to Rilke’s earlier translators and his benefitting from their successes and their shortcomings. Elsewhere, still in third-person critique, Gass compares his effort in translating a particular line to someone “who flails like [he is] drowning here” (80). About the difficulty of translation in general, Gass writes, “The individuality, the quirkiness, the bone-headed nature of every translation is inevitable” (61).

Nevertheless, Gass obviously believed literary translation was worthwhile, and with proper care it could be done well. Even though something is always left behind, he says that “[t]he central ideas of the stanza, provided we have a proper hold on them, can be transported without loss” (51). Gass goes into detail about some of the pitfalls of translating, and perhaps chief among them is that “[m]any translators do no bother to understand their texts [because t]hat would interfere with their own creativity and with their perception of what the poet ought to have said.” He adds that such translators “would rather be original than right,” comparing their work to a type of thievery whereby “they insist on repainting a stolen horse” (69). In the final analysis, a worthwhile translation is one that “allow[s] us a glimpse of the greatness of the original” (53). Such a translation does not come easily, emphasizes Gass, who was known for his obsessive revising: “It will usually take many readings to arrive at the right place. Somewhere amid various versions like a ghost the original will drift” (54).

Gass’s translations of Rilke’s poetry (and some of his prose) are sprinkled throughout Reading Rilke, but the climactic section is a straightforward collection of Gass’s translations of the Duino Elegies,2 without commentary. These poems began appearing in 1978 when The American Poetry Review published Gass’s translations of the first and ninth elegies, and they concluded the same year the collection appeared, 1999, when Conjunctions and The Minnesota Review published the seventh and fifth elegies respectively. Even though critics have been reluctant to recognize the significance of Gass’s translations of Rilke, Gass himself consistently gave them pride of place. At the celebration of Gass’s ninetieth birthday, on the campus of Washington University in St. Louis, the author read excerpts from his works over the decades, essentially in chronological order, with the exception that he saved his reading of Rilke’s “The Death of the Poet” for his finale—a dramatic conclusion to be sure given that the birthday celebration had to be postponed by several months due to Gass’s deteriorating health (see my post, which includes a link to a video of the entire reading). Moreover, Gass’s final authorized work was The William H. Gass Reader, published in 2018, a year after his death; however, Gass was able to see the book into press, selecting its contents and their order himself. The nearly 1,000-page reader opens with Gass’s translation of an untitled poem from Rilke’s The Book of Hours (“Put my eyes out”); and Gass ended the reader with an essay titled “The Death of the Author,” echoing Rilke’s poem “The Death of the Poet.”

To publish Reading Rilke, Gass had to force himself to complete his translations of the Duino Elegies, a project on which he’d been working nearly as long as he’d worked on his magnum opus The Tunnel—that is, more than twenty years. He said finishing the book was necessary to “get rid of [Rilke’s] ghost” (Abowitz 147), but the exorcism didn’t work, given the evidence of the prominent place Gass reserved for Rilke for the remainder of his life. As a disciple of the Master I of course believe there is too little attention paid to William Gass, period, but his translations of Rilke and the book Reading Rilke have generated almost no scholarly attention whatsoever—which translates to an inverse correlation given the primacy of Rilke in Gass’s world. Indeed, in “The Seventh Elegy” Gass discovered the core secret to living a meaningful life: to cherish, to internalize and thus immortalize “great things,” like poetry, literature and art. He writes, “Those few attainments which display the grace of great things, we must take into ourselves and save from an indifferent multitude. Because all our knowledge, even the gift of a pleasant life, comes to nothing if we know more, enjoy more, only to destroy more” (165).

I encourage you to take into yourself Reading Rilke and the Master’s masterful translations of Rainer Maria Rilke.

Notes

- The Acknowledgments page for Reading Rilke does not wholly agree with William Gass’s own vita (released to me by Mary Henderson Gass). For example, the vita lists the earliest published Rilke translations as “The Panther” and “Torso of an Archaic Apollo” in North Country, 1975; and then indicates that the latter was reprinted in River Styx 8 in 1981. North Country does not appear on the Acknowledgments page. Nor does Schreibheft 54, credited with first publishing “The First Elegy” in 2000; nor does The Eliot Review, credited with publishing “Marionette Theater” (undated but presumably between 1984 and 1998). I’m not sure what to make of these omissions, other than perhaps Gass forgot and did not consult his vita when preparing Reading Rilke.

- Gass’s translations of the Duino Elegies are not available online, but other translations are accessible, including A. S. Kline’s at the poetry in translation site. An added bonus is that Kline’s elegies are illustrated by photos of Rodin’s sculptures.

Works Cited

Abowitz, Richard. “Still Digging: A William Gass Interview.” Conversations with William H. Gass, edited by Theodore G. Ammon, UP of Mississippi, 2003, pp. 142-148.

Fogel, Stanley. “William H. Gass.” The Review of Contemporary Fiction, vol. 25, no. 2, 2005, pp. 7-45.

Gass, William H. Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation. Basic Books, 1999.

—. The William H. Gass Reader. Knopf, 2018.

Hix, H. L. Understanding William H. Gass, U of South Carolina P, 2002.

Holloway, Watson L. William Gass, Twayne, 1990.

Ziegler, Heide. “Three Encounters with Germany: Geothe, Hölderlin, Rilke.” The Review of Contemporary Fiction, vol. 24, no. 3, 2004, pp. 46-58.

Accidental Poets: Paul Valéry’s influence on William Gass

The following paper was presented at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture Since 1900, held at the University of Louisville February 18-20. Others papers presented were “The Poet Philosopher and the Young Modernist: Fredrich Nietzshe’s Influence on T.S. Eliot’s Early Poetry” by Elysia C. Balavage, and “Selections from ‘The Poetic Experiments of Shuzo Takiguchi 1927-1937’” by Yuki Tanaka. Other papers on William H. Gass are available at this blog site; search “Gass.”

In William H. Gass’s “Art of Fiction” interview, in 1976, he declared two writers to be his guiding lights—the “two horses” he was now “try[ing] to manage”: Ranier Maria Rilke and Paul Valéry. He added, “Intellectually, Valéry is still the person I admire most among artists I admire most; but when it comes to the fashioning of my own work now, I am aiming at a Rilkean kind of celebrational object, thing, Dinge” (LeClair 18). That interview for The Paris Review was exactly forty years ago, and viewing Gass’s writing career from the vantage point of 2016, I am here to suggest that, yes, Rilke has been a major influence, but Valéry’s has been far greater than what Gass anticipated; and in fact may have been even greater than Rilke’s in the final analysis. Assessing influence, however, is complicated in this case, I believe, because a large part of Gass’s attraction to Valéry’s work in the first place was due to his finding the Frenchman to be a kindred spirit. Hence it is difficult to say how much of Gass is like Valéry because of Valéry’s influence and how much is because of their inherent like-mindedness.

A quick survey of Gass’s work since 1976—which includes two novels, a collection of novellas, a collection of novellas and stories, and eight books of nonfiction—may imply that Rilke has been the greater influence, as Gass intended. After all, Gass’s magnum opus, The Tunnel (1995), for which he won the American Book Award, centers on a history professor of German ancestry who specializes in Nazi Germany (Rilke allusions abound); and his other post-1976 novel, Middle C (2013), for which he won the William Dean Howells Medal, centers on a music professor born in Vienna whose special interest is Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg; and, glaringly, there is Gass’s Reading Rilke (1999), his book-length study of the problems associated with translating Rilke into English. However, a more in-depth look at Gass’s work over these past four decades reveals numerous correspondences with Valéry, some of which I will touch upon in this paper. The correspondence that I will pay particular attention to, though, is that between the title character of Valéry’s experimental novella The Evening with Monsieur Teste (1896) and the protagonist of Gass’s Middle C, Joseph Skizzen.

Before I go further, a brief biographical sketch of Paul Valéry: He was born in 1871, and published two notable works in his twenties, the essay “Introduction to the Method of Leonardo da Vinci” and Monsieur Teste; then he stopped publishing altogether for nearly twenty years—emerging from his “great silence” with the long poem “The Young Fate” in 1917 at the age of forty-six. During his “silence,” while he didn’t write for publication, he did write, practically every day, filling his notebooks. Once his silence was over, he was catapulted into the literary limelight, publishing poems, essays, and dramas, becoming perhaps the most celebrated man of letters in France. By the end of his life in 1945 he’d been nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature a dozen times.

The title for this paper comes from Gass himself. In his 1972 review of Valéry’s collected works, in the New York Times Book Review, he wrote that Valéry “invariably . . . [pretended] he wasn’t a poet; that he came to poetry by accident” (The World Within the Word 162). By the same token, Gass has insisted in numerous interviews (and he’s given many, many interviews) that he’s not a poet, that the best he can achieve is an amusing limerick. Others, however, have asserted that Gass’s fiction is more akin to poetry than prose, that his novellas and novels are in essence extremely long prose poems; and in spite of his insistence on his not being a poet, he would seem to agree with this view of his work. In a 1998 interview, for instance, Gass said, “I tend to employ a lot of devices associated with poetry. Not only metrical, but also rhyme, alliteration, all kinds of sound patterning” (Abowitz 144). Moreover, about a decade earlier he said that “all the really fine poets now are writing fiction. I would stack up paragraphs of Hawkes, Coover, Elkin, or Gaddis against the better poets writing now. Just from the power of the poetic impulse itself, the ‘poets’ wouldn’t stand a chance” (Saltzman 91). Critics have tended to include Gass in the group of writers whom Gass described as poet-novelists.

For your consideration, from The Tunnel:

A smile, then, like the glassine window in a yellow envelope. I smiled. In that selfsame instant, too, I thought of the brown, redly stenciled paper bag we had the grocer refill with our breakfast oranges during the splendid summer of sex and sleep just past—of sweetly sweating together, I would have dared to describe it then, for we were wonderfully foolish and full of ourselves, and nothing existed but your parted knees, my sighs, the torpid air. It was a bag—that bag—we’d become sentimental about because (its neck still twisted where we held it) you said it was wrinkled and brown as my balls, and resembled an old cocoon, too, out of which we would both emerge as juicy and new as the oranges, like “Monarchs of Melody,” and so on, and I said to you simply, Dance the orange (a quotation from Rilke), and you said, What? There was a pause full of café clatter. (160-61)

And beyond Gass’s poetic prose, he has written actual poems, besides the off-color limericks that populate The Tunnel. In Middle C, for example, there is a longish, single-stanza poem written via the persona of the protagonist, Joseph Skizzen. It begins, “The Catacombs contain so many hollow heads: / thighbones armbones backbones piled like wood, / some bones bleached, some a bit liverish instead: / bones which once confidently stood / on the floor of the world” (337). And, perhaps more significantly, there are the translated poems in Reading Rilke. There was a celebration held at Washington University in St. Louis in honor of Gass’s ninetieth birthday, Passages of Time, and he read from each of his works in chronological order, except he broke chronology to end with his translation of Rilke’s “The Death of the Poet,” which concludes,

Oh, his face embraced this vast expanse,

which seeks him still and woos him yet;

now his last mask squeamishly dying there,

tender and open, has no more resistance,

than a fruit’s flesh spoiling in the air. (187)

It was a dramatic finale, especially since the event was supposed to be in July, near Gass’s birthday, but he was too ill to read then; so it was rescheduled for October, and the author had to arrive via wheelchair, and deliver the reading while seated. Happily, he was able to give another reading, a year later, when his new book, Eyes, came out. (I wasn’t able to attend the Eyes reading, so I’m not sure how he appeared, healthwise, compared to the Wash U. reading.)

My point is that, like Valéry, Gass has downplayed his abilities as a poet, yet his literary record begs to differ. The fact that he broke the chronology of his birthday celebration reading to conclude with a poem—and he had to consider that it may be his final public reading, held on the campus where he’d spent the lion’s share of his academic life—suggests, perhaps, the importance he has placed on his work as a poet, and also, of course, it may have been a final homage to one of his heroes. In spite of Gass’s frailness, his wit was as lively as ever. When he finished reading “The Death of the Poet,” and thus the reading, he received an enthusiastic standing ovation. Once the crowd settled, he said, “Rilke is good.”

Evidence of the earliness of Valéry’s influence or at least recognized kinship is the preface to Gass’s iconic essay collection Fiction and the Figures of Life (1970), which Gass devotes almost entirely to the connection between the collection’s contents and the way that Valéry had assembled his oeuvre. Gass writes, “It is embarrassing to recall that most of Paul Valéry’s prose pieces were replies to requests and invitations. . . . [H]e turned the occasions completely to his account, and made from them some of his profoundest and most beautiful performances” (xi). Gass continues, “The recollection is embarrassing because the reviews and essays gathered here are responses too—ideas ordered up as, in emergency, militias are”; and then he describes his book as a “strange spectacle” in which he tries “to be both philosopher and critic by striving to be neither” (xii). So, Gass recognizes the parallel between the forces at work in Valéry’s literary life and his own. Gass has readily acknowledged the slowness with which his fiction has appeared (notably, it took him some twenty-six years to write The Tunnel), citing two reasons: the slowness with which he writes, and rewrites, and rewrites; but also the fact that he regularly received opportunities to contribute nonfiction pieces to magazines and anthologies, and to give guest lectures, and they tended to pay real money, unlike his fiction, which garnered much praise but little cash over his career.

This parallel between the circumstances of their output is interesting; however, the correspondences between Valéry’s creative process and his primary artistic focus, and Gass’s, is what is truly significant. In his creative work, Valéry was almost exclusively interested in describing the workings of the mind, of consciousness; and developing complex artistic structures to reflect those workings. T. S. Eliot noted Valéry’s dismissiveness of the idea of inspiration as the font of poetic creation. In Eliot’s introduction to Valéry’s collection The Art of Poetry, he writes, “The insistence, in Valéry’s poetics, upon the small part played [by ‘inspiration’ . . .] and upon the subsequent process of deliberate, conscious, arduous labor, is a most wholesome reminder to the young poet” (xii). Eliot goes on to compare Valéry’s technique and the resulting work to that done by artists in other media, most notably music composers: “[Valéry] always maintained that assimilation Poetry to Music which was a Symbolist tenet” (xiv). James R. Lawler echoes Eliot when he writes that Valéry “makes much of the comparison of poetry to the sexual act, the organicity of the tree, the freedom of the dance, and the richness of music—especially that of Wagner” (x).

The wellspring of music composition as a source of structural principles for poetry (or highly poetic prose) is arguably the greatest correspondence between Valéry as artist and Gass as artist. Examples abound, but The Tunnel and Middle C offer the most radiant ones. For the The Tunnel Gass developed a highly synthetic structure based on Arnold Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School’s musical theory of a twelve-tone system. Consequently there are twelve sections or chapters, and in each Gass develops twelve primary themes or images. He said, “[T]hat is how I began working out the way the various themes come in and out. It’s layered that way too. . . .” (Kaposi 135). In The Tunnel, Gass’s methodology is difficult to discern because Gass gave it a “chaotic and wild” look while in fact it is, he said, “as tightly bound as a body in a corset” (134). He achieved the appearance of chaos by “deliberately dishevel[ing]” the narrative with “all kinds of other things like repetitions [and] contradictions.” He said, “[T]he larger structure must mimic human memory, human consciousness. It lies, it forgets and contradicts. It’s fragmentary, it doesn’t explain everything, doesn’t even know everything” (134). For Middle C, the use of the Schoenberg system is much more overt, with Skizzen, its protagonist, being a music professor whose specialty is Schoenberg and Skizzen’s obsession with getting a statement about humans’ unworthiness to survive just right. Skizzen believes he is on the right track when he writes the sentence in twelve beats, and near the end of the novel he feels he has the sentence perfect:

First Skizzen felt mankind must perish

then he feared it might survive

The Professor sums up his perfect creation: “Twelve tones, twelve words, twelve hours from twilight to dawn” (352). Gass, through his narrator, does not discuss the sentence’s direct correlation to the Second Viennese School’s twelve-tone system, but it does match it exactly.

Let me return to another Valéry-Gass correspondence which I touched on earlier: their concern with the workings of the mind or, said differently, consciousness. Jackson Mathews, arguably the most herculean of Valéry’s translators into English, begins his introduction to Monsieur Teste with the statement that “Valéry saw everything from the point of view of the intellect. The mind has been said to be his only subject. His preoccupation was the pursuit of consciousness, and no one knew better than he that this pursuit led through man into the world” (vii). Valéry’s interest in the mind was present in his earliest published work, the essay on Leonardo’s method and, even more obviously, Monsieur Teste, that is, “Mr. Head” or “Mr. Brain as Organ of Observation” or something to that effect. However, it was during Valéry’s twenty-year “silence” that he delved into the phenomenon of consciousness most critically. Gass writes, “Valéry began keeping notebooks in earnest, rising at dawn every day like a priest at his observances to record the onset of consciousness, and devoting several hours then to the minutest study of his own mind” (“Paul Valéry” 163). As noted earlier, Gass fashioned The Tunnel, all 800 or so pages of it, to mimic the human mind in its intricate workings. In Middle C, Gass pays much attention to Skizzen’s thought processes, especially his copious writing, revising, critique of, and further revising of his statement about humans’ unworthiness for survival. Such concerns are everywhere in Gass’s work, including his most recently published, the collection of novellas and stories, Eyes. I would point in particular to the novella Charity, a challenging stream-of-consciousness narrative, all a single paragraph, that mercilessly bounces between the main character’s childhood and his present, and, chaotically, various times in between, all the while sorting through his feelings about the act of charity and how he came to feel about it as he does in the now of the story.

In the limited time remaining, I’ll turn to the correspondence between Valéry’s character Monsieur Teste and Gass’s Joseph Skizzen (though I think William Kohler, the narrator of The Tunnel, has significant Teste-esque qualities as well). The convention of The Evening with Monsieur Teste is that the narrator is a friend of Edmond Teste’s, and he goes about attempting to describe his friend’s character. There is very little action per se, and as such almost nothing in the way of plot, in a conventional sense at least (very Gassian in that regard). He tells us that he came to “believe that Monsieur Teste had managed to discover laws of the mind we know nothing of. Certainly he must have devoted years to his research” (11). In Middle C, Joseph Skizzen is obsessed with what he calls his Inhumanity Museum, essentially a record, largely in the form of newspaper clippings and personal notes, of humans’ ceaseless cruelty to one another. The collection is associated with his ongoing struggle to word just so his statement about humans’ unworthiness to survive. Monsieur Teste becomes almost a recluse, desiring little contact with other people. He is married, but the narrator suggests that Monsieur and Madam Teste’s relationship is more platonic than passionate, due to Edmond’s preference for the intellectual over the emotional. Similarly, Skizzen never marries in Middle C, and in fact never has sex—he flees as if terrified at the two attempts to seduce him, both by older women, in the novel. Ultimately he ends up living with his mother in a house on the campus where he teaches music history and theory, his few “pleasures” consisting of listening to Schoenberg, assembling his Inhumanity Museum, and revising his pet statement. What is more, Teste’s friend describe Edmond’s understanding of “the importance of what might be called human plasticity. He had investigated its mechanics and its limits. How deeply he must have reflected on his own malleability!” (11-12). Skizzen’s malleability is central to his persona in Middle C. He goes through several name changes, moving from Austria to England to America, and eventually fabricates a false identity, one which includes that he has an advanced degree in musical composition, when in fact his knowledge of music is wholly self-taught. One of the reasons he gravitates toward Schoenberg as his special interest is because of the composer’s obscurity and therefore the decreased likelihood that another Schoenberg scholar would be able to question Skizzen’s understanding of the Austrian’s theories. But over time Skizzen molds himself into a genuine expert on Schoenberg and a respected teacher at the college—though his fear of being found out as a fraud haunts him throughout the novel.

To utter the cliché that I have only scratched the surface of this topic would be a generous overstatement. Perhaps I have eyed the spot where one may strike the first blow. Yet I hope that I have demonstrated the Valéry-Gass scholarly vein to be a rich one, and that an even richer one is the Valéry-Rilke-Gass vein. A couple of years ago I hoped to edit a series of critical studies on Gass, and I put out the call for abstracts far and wide; however, I had to abandon the project as I only received one email of inquiry about the project, and then not even an abstract followed. Nevertheless, I will continue my campaign to bring attention to Gass’s work in hopes that others will follow me up the hill, or, better still, down the tunnel. Meanwhile, if interested, you can find several papers on Gass’s work at my blog.

Works Cited

Abowitz, Richard. “Still Digging: A William Gass Interview.” 1998. Ammon 142-48.

Ammon, Theodore G., ed. Conversations with William H. Gass. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2003. Print.

Eliot, T. S. Introduction. The Art of Poetry. By Paul Valéry. Trans. Denise Folliot. New York: Pantheon, 1958. vii-xxiv. Print.

Gass, William H. Charity. Eyes: Novellas and Short Stories. New York: Knopf, 2015. 77-149. Print.

—. Preface. Fiction and the Figures of Life. 1970. Boston, MA: Nonpareil, 2000. xi-xiii. Print.

—. Middle C. New York: Knopf, 2013. Print.

—. Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation. 1999. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

—. The Tunnel. 1995. Champaign, IL: Dalkey Archive, 2007. Print.

—. The World Within the Word. 1978. New York: Basic Books, 2000. Print.

Kaposi, Idiko. “A Talk with William H. Gass.” 1995. Ammon 120-37.

Lawler, James R. Introduction. Paul Valéry: An Anthology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1977. vii-xxiii. Print.

LeClair, Thomas. “William Gass: The Art of Fiction LXV.” 1976. Ammon 46-55. [online]

Mathews, Jackson. Introduction. Monsieur Teste. By Valéry. Trans. Jackson Mathews. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1989. vii-ix. Print.

Valéry, Paul. Monsieur Teste. 1896. Trans. Jackson Mathew. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1989. Print.

Notes on images: The photo of Paul Valéry was found at amoeba.com via Google image. The photo of William H. Gass was found at 3ammagazine.com via Google image.

When Not to Edit

I’ve been writing for publication since high school (I graduated, ahem, in 1980), and I’ve been editing publications since then, including scholastic publications and the literary journals A Summer’s Reading and Quiddity. In 2012 I founded Twelve Winters Press, and I’ve had a hand in editing each of the books we’ve published (we’ll be releasing our ninth title next month). Editing a book is different, of course, from editing a piece for a journal — but no matter the context, I’ve come to believe that there’s a right time to edit someone’s work, and there’s most definitely a wrong time.

It’s the latter that has prompted me to write this post, and in particular an encounter with the editor-in-chief of a well-respected literary journal which ended in her withdrawing my piece due to “Author unwilling to cooperate with editorial process.” About two years earlier I had a similar encounter with a literary press — but in that case I had signed a contract allowing the press editorial control of the piece, never imagining how far its editor-in-chief would take liberties.

I’m not going to identify the publications and their editors. Even though I disagree with their approaches, I respect that they’re doing important and largely thankless work. I have no interest in blackening their eyes, but there are a lot of editors at work — what with online journals and print-on-demand publishers springing up daily — so I think it’s worth discussing when the right and wrong times to edit are.

I had very similar experiences with the journal and the publisher, so I’m going to focus on the more recent experience with the journal. Last week I received in the mail the issue that my short story “Erebus” was supposed to appear in (I generally try to support the journals that publish my work by buying subscriptions). It’s an attractive little journal, which no doubt contains some very good pieces. It would have been a nice feather in my CV cap.

The problem, as I see it, is one of timing. The story was accepted for publication with no caveats whatsoever on November 29, 2014. Months went by, during which time I supported the journal by including the forthcoming publication on my website and in my bio to other journals — some free publicity if you will. Then I received the following email with my edited story attached:

[March 21 — 7:16 p.m.]

Dear Ted,

I’m sending out copy edits for the upcoming issue, and have attached yours to this message.

My edits are made using the track changes feature, and comments/questions/suggestions are included in comment balloons in the document. Please make any changes within the document with track changes turned on. Please do not accept any of my changes or delete comments, as I will need those to remain in place as references. If everything looks okay to you, please let me know by e-mail (no need to send the document back unless you have made changes).

Thank you and I look forward to including your work in the upcoming issue! Just let me know if you have any questions.

It was obviously a generic email sent to all contributors (which is understandable) because when I opened the document I found there were numerous changes and requests for changes — so “[i]f everything looks okay to you, please let me know by email (no need to send the document back unless you have made changes)” didn’t even apply because there were places here and there where the editor (or another editor) wanted me to replace a word or revise a section to make some other aspect of the story plainer — things to that effect. Also, someone must have read Stephen King’s On Writing and really taken his disdain for adverbs to heart because every adverb in the 3,300-word story was deleted, regardless of how it impacted the meaning of the sentence. Moreover, I’ve developed a style for my literary work that uses punctuation (or doesn’t use it) in nonstandard ways; and the editor had standardized my punctuation throughout.

I was flummoxed. Here are our verbatim exchanges over the next few weeks:

[March 21 — 8:31 p.m.]

Hi, [Editor]. While I can see some improvements here and there, in general the editing is too heavy-handed, for example, the addition of quotation marks and tinkering with italics. I’m well aware of conventional rules, and I’m breaking them. I’m not sure why journal editors accept pieces for publication, then find so much fault with them before publication. I’m ok with considering a wording change or two, but I’m not comfortable with this amount of editing.

If you didn’t care for the story in its original form, you should have rejected it. I’m not sure where that leaves us. Thank you for the time and thought you’ve put into my story, but I disagree with much of what is suggested here. Not angry, just disappointed and a little frustrated.

Ted

* * *

[April 1 — 12:09 p.m.]

Hi Ted,

While I’m aware that you were intentionally breaking stylistic conventions, I added things like quotation marks because they were needed for clarity, i.e., to separate narrative from dialogue. There were some sections where the distinction wasn’t clear without them. Many of the other changes I implemented were for our house style. However, those edits are minor in light of many of the other edits that are suggested, notably in the comments. I edit every piece before publication…that’s what editors do. So, that is to say that the edits aren’t personal, and in my experience, that is the reaction of many new writers, to take edits personally somehow. So the bottom line is that if you’re not comfortable making any changes to your work, then I’ll withdraw it from the issue and you’re free to shop it elsewhere.

Let me know.

* * *

[April 1 — 1:42 p.m.]

Edit “Erebus” however you see fit, [Editor]. Thank you for including it in the journal.

* * *

[April 1 — 1:50 p.m.]

There are editorial suggestions in the comments that require your feedback. I have attached the piece again. Below are the instructions for editing in track changes:

Edits are made using the Track Changes feature in Word. Please look over the edits and changes I have made, and let me know if you accept these or have any questions. Of course, if there is anything you disagree with, please let me know and we can discuss it to try to reach a mutually agreeable solution. If you make any further changes, please make sure that you do so with Track Changes toggled on, so that I can be sure that your work makes it into the final copy; otherwise, I may not see it.

Please have edits back to me by 4/5, if possible

* * *

[April 1 — 2:09 p.m.]

Gosh, [Editor]. You guys seem to be making this as difficult as you can. I don’t agree with any of the editorial suggestions/questions, so it’s difficult for me to find a better way of saying things. I did all that work before I sent it to you, so now we’re into potay-to/potah-to, and I don’t know how to say things the way you want to hear them. I looked at your comments again to see if I could get into the spirit of things. I’ve been publishing my writing (fiction, poetry, academic writing, essays, reviews) for thirty-five years, and I’ve been editing and publishing other people’s work for nearly that length of time, and I’ve never experienced a process like this one before. I disagree with your comments on the story, but I’ve given you free rein to edit it however you like. If you feel like you can make the story better, please do so. I’m generously putting my faith in your editorial skills. I don’t know what more I can do than that.

* * *

[April 1 — 2:10 p.m.]

You can consider “Erebus” withdrawn from the issue.

* * *

[April 1 — 2:40 p.m.]

Thank you. That’s been my inclination too.

All the best,

t

In offering her carte blanche, I wasn’t trying to be a smart-ass (ok, maybe a tiny bit). After all, her original email said I didn’t need to return the edited document. But, truly, I didn’t see the point of attempting to guess what wording would make her happy, like trying to sell shoes to someone — “Something with a heel perhaps? No, a loafer? Maybe a half-boot?” There were two aspects of the exchange that I found particularly baffling (and they parallel the experience I had with the literary publisher a couple of years earlier).

One thing I’m baffled by is her surprise (and irritation, I think) that I would take the edits personally. She characterizes it as a shortcoming of “many new writers” (rather condescendingly, I feel). Well, I ain’t no new writer, so that’s not the problem. I think all writers and poets of literary work take their diction, syntax, and punctuation choices seriously, so why wouldn’t they be emotionally invested in those choices? And having those choices edited to conform to “house style” is especially irksome, which brings me to the second thing I’m baffled by: house style?!?

Why in the world would a literary journal have a house style that applies to the actual content of its stories and poems? Of course they would have a style when it comes to things like the font they use for titles and authors’ names, and they should be consistent in placing a translator’s name at the head or foot of a published piece — things like that. But a style for the content of the literary work itself? It’s, well, ridiculous. “Dear Mr. McCarthy, please insert quotation marks in your dialogue … and Mr. Joyce, no more dashes in your dialogue … and Mr. Shakespeare, stop making up words! — if it’s not in the dictionary, we won’t publish it … Sorry, our hands are tied, house style and all.”

The publisher I had a run-in with two years ago insisted on editing my literary book according to the Chicago Manual of Style. The CMS, really?

All right, so I disagree with editors imposing arbitrary styles on literary work, but that’s their prerogative, I suppose. What I find downright unethical is accepting a piece for publication without any reservations, waiting several months, then making significant edits that the author is supposed to accept or else (the publisher flexed her contract language and forced CMS on my work, while the lit journal editor-in-chief withdrew my story, in something of a snit I think).

A better approach, I believe, is the one we use at Twelve Winters Press. Our editors and readers offer authors feedback — food for thought, as I call it — but the decisions when it comes to the final presentation of the work rest with the writers and poets. If there are reservations about some aspect of the work, those should be ironed out before it’s formally accepted. There should be no surprises and heavy-handed editing months and months later. When our contributing editor John McCarthy was reading submissions for his Extinguished & Extinct anthology, he had some suggestions for authors in a few instances, but they were made up front, before offering publication. Obviously there are many editors and publishers who operate this way, and as a writer I’ve had the good fortune to work with several of them.

What is more, in the case of the literary journal editor, she took my story out of circulation during the peak reading months of the year, from November to April. Most lit journals, due to their being affiliated with universities, follow an academic calendar and many begin folding their tents for the year in April or May. It seems odd to me, also, that the editor felt I was over-reacting to changes that were, in her view, minor — yet she couldn’t see fit to letting the story run in its original form when I expressed my strong preference to leave the story be. Pulling the story after five months due to a disagreement over minor edits could be seen as an over-reaction too.

It’s my impression that with both the literary publisher and the editor-in-chief, the problem arose in part because another editor had acquired or accepted the work; then someone else took charge of it before it was published. If so, then the problem is in-house. If the readers and editors acquiring and accepting work have different artistic sensibilities from the top-dogs on the masthead, it’s going to create problems for the authors they’re publishing. Ultimately, though, I’d like to see all editors respect their authors and their authors’ work enough to give them the benefit of artistic doubt. In the commercial, mass market world of publishing, I can see where publishers and editors may feel the need to pull rank since capitalism drives their decisions. They may well know better than the author what phrasing, what title or what cover image may enhance sales.

But literary publishing isn’t about sales — and don’t I know it! It’s about being true to the work and respecting the author’s artistic vision . . . or at least it ought to be.

Interview with John McCarthy: Extinguished Anthology

Last March, Twelve Winters Press released [Ex]tinguished & [Ex]tinct: An Anthology of Things That No Longer [Ex]ist, edited by the Press’s contributing editor John McCarthy. At the time I didn’t have the presence of mind to interview John about the book, but the Press has recently announced its Pushcart Prize nominees from the anthology, so I thought it would be appropriate to post an overdue interview.

John and I have known each other since around 2008 because of our mutual involvement with Quiddity international literary journal and public-radio program. I was a founding editor who eventually took a step or two back to prose reader; John was an intern who eventually assumed the role of assistant editor. When I launched Twelve Winters Press in 2012, John was quick to lend his support. Knowing his talents and work ethic I was happy to hand him the reins on an editorial project for the Press. In the winter of 2013 we sat down to a Thai dinner and brainstormed possible themes for an anthology. The ideas were flying fast and furious. I recall that I spitballed the possibility of a collection of literary zombie stories. John was … dubious. Somehow we eventually came up with the general idea of extinction, which was refined to extinguished and extinct–and John, as I knew he would, hit the ground running.

We composed the wording for the call for submissions of poems, prose poems and flash fiction, and posted it on Submittable and here and there. Then I sat back and let John and the Press’s associate editor Pamm Collebrusco do what they do so well. They meticulously read and sifted through the submissions that soon began pouring in, selected their favorites and worked through the editing process. John designed the cover and interior pages. I got involved again at the very end for an additional proofreading and to actually publish the anthology, which ultimately offered the work of 37 contributors from five countries. I couldn’t be more pleased with what John and Pamm had produced.

Here, then, is my interview with John (via email) about his editing the anthology.

What attracted you to the theme of “extinguished and extinct”? What about it made you think it would yield plenty of interesting material?

Part of good writing–part of its goal–is to craft something timeless, something universal people can relate to. When I started brainstorming themes, I decided the best way to do this was to address something permanent. I thought of a line from Larry Levis’s poem, “My Story in a Late Style of Fire,” when the speaker is lamenting a former lover and explains “even in her late addiction & her bloodstream’s / Hallelujahs, she, too, sang often of some affair, or someone / Gone, & therefore permanent.” And what is more permanent than the total, absolute absence of someone or something? Extinction, death. I didn’t want the anthology to be just about a personal death. There are plenty of grief anthologies out there, but in a sense, all poetry is about longing, grieving, lamenting, or venerating the fleeting. I wanted to expand this idea of the permanence of loss to anything: things that are endangered of becoming extinct; things that are extinct that deserve a modern voice; as well as a traditional elegy for a person or thing. I wanted it to address personal emotions as well as open up dialogues about socially conscious topics such as the importance of eco-preservation as well as race and gender. I didn’t want it to be just an anthology about wooly mammoths or dinosaurs, I wanted writers to redefine or reinterpret the word extinction. I wanted them to apply this word to specific entities and abstract concepts. I wanted to make something permanent by pulling it from permanence. Levis is lamenting this woman because she is lamenting someone she lost before him, so it’s this other absence–her own experience with extinction–that inhibits her ability to be totally present with Levis, so in a way, extinction for me means seeing beyond the duality of things dead and things living. It means appreciating absence, acknowledging it in such a way that it really isn’t absent anymore. Once something is, it is forever. That’s a certain kind of philosophy with a lot of debate to it, but it was the jumping ground to a lot of great work which I received.

How many submissions did you receive (more or less)? Were you surprised by the response?

I got about 1,500 submissions in total. I wasn’t surprised considering how well the calls for submission was promoted. My surprise was with how much quality writing I received and had to sift through. I was worried that the extinction theme would generate a ridiculous amount of genre stuff dealing with zombies, nuclear fallout, all that apocalyptic stuff, which is fine in its own regard, but it was not what I was looking for with the anthology. I received a couple submissions like that, but not as many as I would have thought. I had to decline a lot of good work, too. I had 37 contributors in total, but if I had unlimited page space, I would have accepted around 50 I think. I got quality submissions dealing with everything from extinct animals, to foreign dialects, to pokemon, to jukeboxes, even rotary phones, libraries, and turn-tables. It was exciting to see so many people interpreting and reimagining these historical contexts in new voices. It was cool to look at things that are “gone, and therefore permanent,” but were given light to everything we lost.

Did ideas for any other themed anthologies come to you while reading through the submissions?

Yes, I want to do an anthology dealing with the opposite of this anthology. “Things not yet existing.” I want to see how imaginative and prophetic writers could get with things that don’t yet exist in the world or how curet existing things might get reimagined in a contemporary context. Obviously, I would worry about receiving too many hard science fiction submissions, but I would open it up to any extrapolation of the idea dealing with things that are existing currently. Like maybe a Latino president would be an awesome prophecy, a new kind of rug that floats around the house, maybe a new way of giving birth, or escalators to the moon. I would really look for inventiveness. I would also like to do an anthology of short stories or formal verse at some point. I always have ideas, always looking for platforms to execute them.

How did reading submissions and editing the anthology impact your own writing?

I love working with the persona poem and the elegy. I think it is fun to piggyback off of other persons or events in time. It helps develop a stronger sense of empathy within the work. It was a good exercise to work and edit other people’s interpretations of their personas and the elegies. There is so much you can do with projection. Memory is the world within the world. Working with this anthology helped me access, explore, and appreciate that inner world.

John McCarthy has had work appear or is forthcoming in RHINO, The Minnesota Review, Salamander, Jabberwock Review, Midwestern Gothic, Oyez Review, and The Pinch among others. He is an MFA candidate at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. He lives in Chicago, Illinois, where he is a contributing editor at Poets’ Quarterly and the assistant editor of The Museum of Americana and Quiddity international literary journal and public-radio program. Follow him @jmccarthylit.

Interview with J.D. Schraffenberger: The Waxen Poor

I don’t recall the exact year that I met Jeremy Schraffenberger (2005? — give or take), but it was definitely at the University of Louisville during its annual literature and culture conference. I chaired a critical panel on which Jeremy was presenting a paper. As the day progressed and we ran into each other here and there, we discovered that while we both enjoyed academic writing, creative writing was our true passion — mine, specifically, fiction, and his poetry. Over the years we often met up in Louisville, and when my first novel, Men of Winter, came out in 2010, Jeremy was kind enough to help me set up a reading in Cedar Falls, Iowa, as part of Jim O’Laughlin’s Final Thursday Reading Series. By then Jeremy (who publishes and edits under the initials J.D.) was on the tenure track in the English Department at the University of Northern Iowa and part of the editorial masthead of the North American Review. In the summer of 2013 I was able to return the favor and arranged for Jeremy to come to Springfield, Illinois, to be a “Poet in the Parlor” at the historic Vachel Lindsay Home; while he was in town, he also gave a fascinating talk on the history of the North American Review and its fast-approaching bicentennial (in 2015) — the talk was hosted by Adam Nicholson at The Pharmacy Art Center.

In 2012, I established Twelve Winters Press with the intention of using it to bring out my books, or keep them in print, and to bring out the literary work of others. Last winter I contacted Jeremy about possibly working with the Press on some sort of project under his editorial direction — and much to my delight he informed me he had a collection, The Waxen Poor, that he was interested in publishing. He sent me the manuscript, which I was able to read (again, much to my delight) before meeting him in Louisville for the conference this past February. After his reading in the beautiful Bingham Poetry Room in Ekstrom Library, we sat down to cups of coffee in the Library’s Tulip Tree Café and discussed his collection and made plans to bring it out this summer.

I’m happy to report that The Waxen Poor is indeed out. See Twelve Winters Press’s Poetry Titles page for full details.

I interviewed Jeremy via email about his intriguing collection, which includes poems published in such notable journals as Brevity, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Notre Dame Review, and Prairie Schooner, among many others. What follows are his unedited responses to my questions. When I had the honor of introducing Jeremy at the Vachel Lindsay Home, I said that I always enjoyed his readings because he was the sort of poet that I respected most: one who takes his poetry seriously but not himself. I believe this engaging combination of qualities is apparent here.

What’s the time span represented by the poems in The Waxen Poor? That is, how early is the earliest poem and how recent the most recent?

The earliest piece in the collection — and the one that really sparked this whole project — is the prose poem “Full Gospel,” which was originally published in the summer of 2006 in Brevity and was later reprinted in Best Creative Nonfiction. I bring this up only because I find the question of genre interesting. I originally wrote “Full Gospel” as a poem, but then as I started to revise, I became less and less interested in lines and line breaks and more and more interested in segmentation or braiding as a way to craft the piece. I can’t say that I was consciously blurring generic boundaries — I was just trying to write something true — but I’m still not quite sure how to categorize it. Is it an essay? A poem? A prose poem? In the end, I suppose, that’s not terribly important, but insofar as it might reveal something about the composition process — in this case, I think, how memory is organized — I think it’s an intriguing question.

Two other early pieces are the first one in the collection, “Brother Tom,” and the last, “Born for Adversity.” It was important, I think, that I knew where I was heading as I wrote and revised. I would certainly not consider The Waxen Poor a novel in verse, but I did feel that there was something of a narrative arc, if not an actual plot — even if it remained subtextual — that guided me along as I worked. I had a clear sense of the beginning and I knew the end, and so the challenge became what to do with the long expansive middle. As Margaret Atwood wrote, “True connoisseurs … are known to favor the stretch in between, since it’s the hardest to do anything with.”

The most recent poem in the collection is the sequence of “Judas” poems, which came as something of a surprise to me as I wrote them. I hadn’t expected to cast “Brother Tom” as a Judas character, but there it is. Sometimes you can’t — and maybe you shouldn’t — control your characters. You can see that I’m trying to complicate Judas/Tom, though, by calling him “A man of tradition, assassin of the ages, / My translator, my traitor, my Judas, my friend” — the same kind of complication I’m attempting to bring to the entire collection. These “Judas” poems came to me about three years ago, and so The Waxen Poor represents five years of work.

Did you set out to write a collection around the topic of “Brother Tom,” or did the concept of collecting them develop over time? Either way, can you describe the thought process behind the collection?

In my mind The Waxen Poor was always a cohesive project. After “Full Gospel” I began organizing individual pieces around the character of “Brother Tom.” I wanted to explore this fraught relationship between two brothers, each of whom is like the other but also quite different — one a poet, the other struggling with mental illness. The poems are meant to be both personal and more broadly mythological, and I’ve tried to balance (or “harmonize” might be a better word) the experiential with the imagined, the everyday with the elevated. You could also say that the project is in some ways a coping mechanism, like Eliot’s “fragments I have shored against my ruins.” That is, how are we to deal with the pain and suffering in the world but through our art? When trying to understand and contend with something like mental illness, some of us turn to art, to poetry, for answers.

Many of the poems seem to be highly personal in their subject matter. Can you discuss the process of tapping into those emotions via the creative process?

As I said, I see the collection as something of a coping mechanism — but then in some ways, all art functions as a mechanism of this kind, even if you’re not dealing with emotionally fraught subjects. What do we make of this world around us and all of the various experiences we have? How do we give our lives any kind of meaning but by forming it, shaping it? Even the most experimental, appropriative forms of conceptualism in which all subjectivity has been evacuated are ways to cope.

That said, there are some poems in The Waxen Poor I can’t read in public anymore because they’re too emotionally difficult for me to get through, but I think that probably means something important is happening. I try to tell this to my creative writing students, that if something is too painful to write, you should write it, not for the sake of therapy — though that might end up being part of it — but because when a poem is difficult in this way, you’re getting near something that you care deeply about, even if it’s in ways that you can’t quite articulate yet. When we find a form for our pain or confusions, we’re allowing others to identify with it, with us. We’re letting our readers in.

The form of these poems varies considerably, and there are even some prose poems included in the collection. Can you discuss the interplay between subject and form for you as a poet? For example, how much one influences the other?

I’m a formalist insofar as I believe that form is meaning. To sever the two is to do a deep violence to the poem — and to misread it entirely. I think it takes a long time before this insight, which is easy enough to say and understand intellectually, sinks in deeply enough for it to be true as a writer. Or at least this has been the case for me. The prose poem is a perfect example of this fusion between form and meaning. I never set out to write the prose poem sequences you find in this collection. Rather, I discovered that this was the form the poem had to take — especially the somewhat surreal ones in which the thoughts and images and phenomena all seem to tumble forth, like consciousness itself. Likewise, some of the unrhymed sonnets in the collection were discovered. That is, as I began writing, I felt the rhetorical movement of the sonnet happening, the turn, and so I began shaping it accordingly. This means paying attention to more than just the “subject,” more than what the poem is supposedly “about,” and opening yourself up to different ways of knowing.

But there are a handful of exceptions. The poem “Abecedarian Advice” is a received form that I didn’t “discover” but rather imposed on myself as a challenge. And the four “Meds” poems are acrostics that spell out the names of the antipsychotic drugs “Haldol,” “Thorazine,” “Zyprexa,” and “Lithium” down the left margins of the poems. I like the way these formal experiments turned out because I found that I ended up thinking about things I never would have thought about before. The somewhat arbitrary restraint can ironically be very liberating. In fact, I think the acrostic is the most underrated form. With other forms, like the sonnet, for example, you’re dealing not only with external characteristics like rhyme and meter but also an internal rhetorical shape that isn’t always the right fit for the poem. The acrostic, though, can accommodate absolutely anything. It gets a bad rap and seems unsophisticated because we’ve all written them in elementary school. But I think there’s something refreshing about the form’s simplicity.